Maureen Okpe

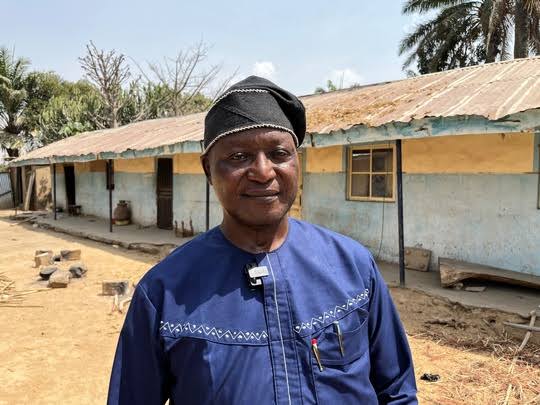

When Luka Binniyat was arrested in November 2021 by the Nigerian Police Force (NPF), he thought he was being abducted. The Kaduna-based journalist was transferred secretly between police stations and locked up with criminals.

His arrest was linked to a report that contradicted the state government’s account of the killings in Southern Kaduna. In the report, Binniyat questioned the official claim that the incident was a farmer-herder clash. He argued that a clash would imply casualties on both sides, yet in this case, only Southern Kaduna farmers were killed.

Binniyat, recalling the incident as his worst experience while practising journalism, said, “The security personnel were ordered to give me the maximum torture treatment. I was moved at night from one cell to another, and at one point, I thought they were taking me out to kill me.”

Read Also: Press Freedom 2025: Stakeholders Champions Global Dialogue on AI

Binniyat spent a total of 288 days in prison; however, this was not his first time. The journalist had faced repeated arrests and harassment under the Cybercrime Act, a law originally designed to combat online fraud and cyberstalking but now often invoked to intimidate journalists and silence critical voices.

According to Binniyat, his first arrest was in February 2016 over a story published in Vanguard about five students of the College of Education who were killed by herdsmen in Kaduna State. Although he later discovered that the report was false and made every effort to retract it, the story was still published. Following an investigation by the state government, he was arrested for spreading fake news and spent 97 days in prison.

Binniyat’s ordeal in the cell

Journalists such as Luka Binniyat have been subjected to imprisonment, harassment, and even torture after publishing reports on corruption and insecurity that displeased government authorities.

Binniyat, while narrating his ordeal with security personnel, said that he had written a series of investigative reports on the killings of residents in Southern Kaduna at the time due to the frequent attacks and had been the least favourite of the then Nasir El-Rufai government.

Samuel Aruwan, who was then the spokesperson for Governor El-Rufai, described the incident as a clash between farmers and herders. However, Binniyat refuted this in his report, accusing Aruwan of concealing the truth.

In response, Aruwan cited the Cybercrime Act, Section 24, which criminalises cyberstalking, online harassment, and messages that could cause annoyance or hatred, claiming that Binniyat’s report exposed him to public hostility. This led to Binniyat’s arrest.

According to Binniyat, this marked the beginning of his most harrowing experience. He alleged that security personnel were ordered to subject him to severe torture. He recounted being detained for two days with hardened criminals who made his life unbearable before he was later moved to another cell, where he was kept in isolation.

Binniyat further revealed that he was secretly transferred between three different police stations, always at night to avoid detection. His first stop was Gabasawa Station on Ibrahim Taiwo Road in Kaduna, a place he described as unfit for survival for anyone in poor health. “At one point,” he recalled, “I thought they were taking me out to kill me.”

Cybercrime Act: A Law Turned Against Journalists

Despite the protections guaranteed in Section 22 of the 1999 Constitution and Article 19 of the Universal Declaration of Human Rights, which uphold the media’s duty to hold the government accountable and affirm the right to seek and share information, the reality for Nigerian journalists is starkly different. Intimidation, arbitrary arrests, and even fatal attacks remain common features of Nigeria’s media landscape.

The press, regarded as the nation’s Fourth Estate, is tasked with holding those in power to account and acting as a crucial bridge between citizens and the state. Yet this mandate has been increasingly undermined, particularly with the enforcement of the Cybercrime Act.

The law’s vague and expansive provisions give security agencies broad discretion to classify critical reporting as a criminal offence, transforming a tool meant for security into a weapon against free expression.

Available data by the IPC–SPJ Hub documented 45 attacks on journalists in 2024, affecting 70 journalists and three media outlets across the country. The Media Rights Agenda (MRA) documented a total of 69 incidents of attacks, harassment, arrests, detention, threats, abductions, and other violations of media rights between January 1 and October 31, 2025.

MRA revealed that government officials were responsible for 74% of these attacks, with the Nigeria Police Force accounting for nearly half, a troubling indicator of institutional hostility toward press freedom.

The effect of these abuses is reflected in international assessments.

Reporters Without Borders’ 2025 World Press Freedom Index places Nigeria at 122nd out of 180 countries, a ten-place decline from the previous year. Together, these figures paint a grim picture of a media environment where journalists continue to suffer arrests, violence, and legal harassment simply for fulfilling their constitutional and democratic obligations.

Like Binniyat, there are other victims

Agba Jalingo, publisher of CrossRiverWatch, was arrested multiple times since 2019, most recently in August 2023, over reports alleging examination malpractice involving Elizabeth Ayade, sister-in-law of former Cross River Governor Benedict Ayade.

Jalingo was detained in Lagos, flown to Abuja, and later released on bail under conditions that included meeting with the complainant. The complaint, citing cybercrime and defamation, demanded a retraction and N500 million in damages.

In his 2019 arrest, Jalingo was charged with treason, terrorism, and disturbance of public peace, largely based on his investigative reports about corruption in Cross River State.

He spent months in prison, with a court eventually ordering compensation for his unlawful detention, a compensation that the government has yet to pay.

Harassment By Security Personnel

While security operatives arrest some journalists, others face multiple harassments by security personnel in the line of duty.

Jide Oyekunle, National Union of Journalists Secretary, FCT Chapter, was harassed while carrying out his duties as a Journalist during the ENDSARS protest in Abuja.

His phones and camera were seized by security operatives in the line of duty.

Oyekunle recounted how he was “dragged away like a common criminal, manhandled, and harassed,” despite efforts by his colleagues to intervene.

He explained that the security personnel refused to return his belongings until reports of his ordeal began circulating widely. “Eight hours later, I was finally called to collect them,” he said, “but by then, all the pictures and videos from the protest had been deleted.”

He explained that the security personnel refused to return his belongings until reports of his ordeal began circulating widely. “Eight hours later, I was finally called to collect them,” he said, “but by then, all the pictures and videos from the protest had been deleted.”

Expressing deep frustration over the persistent mistreatment of journalists, Oyekunle criticised the vague and porous nature of the cybercrime law, arguing that it grants excessive power to security agencies. He described the law as repressive and counterproductive, claiming it was designed to stifle the press rather than protect the public.

According to him, despite calls for reform, the amendments made over the years have only worsened the situation. He referred to the 2015 Cybercrime Act as “an anti-media law targeted at journalists and free speech,” adding that the 2024 amendment “is a Greek gift,” since security agencies, especially the Nigerian police, have weaponised it against the media.

Experts call for action

A human rights activist and Lawyer, Augusta Shahin, raised the need for clear enforcement guidance, robust oversight, and targeted training for security personnel on the limits of the Act.

Shahin said, “The Cybercrime Act should serve as an instrument for protecting citizens from digital harm, not as a means of silencing those who speak truth to power. Its purpose was never to suppress free speech or criminalise the work of journalists and human rights defenders.

After multiple arrests, Binniyat said he is not deterred in his work as a Journalist as he will continue to write stories about issues in society that the government needs to address.

This story was produced as part of Dataphyte Foundation’s project on “Addressing Digital Surveillance and Digital Rights Abuse by State and Non-State Actors” with support from Spaces for Change.