By Senator Iroegbu

With contributions from

Ivuoma Kanu, Lovelyn Agbor-Gabriel and Bertha Ogbimi

Abstract

This paper is an attempt to contain the challenges of monitoring and tracking defence budget and spending in Nigeria. The paper takes a critical look at the prognosis of the security of the Nigerian state, the reactions of the various security apparatus and the significance of the defence sector to the internal security of Nigeria. Provision of security through institutional agencies is not just government’s fundamental obligations to citizens, but it is indispensable for the survival of the country. Fundamentally, state security agencies operate at two levels – the internal and external environments. These environments encapsulate all operational elements of national power which usually inform a state’s national security strategy. However, the paper brings to limelight on how the journalists watchdog role on the activities of the defence sector which includes finances and budget can make them perform their role properly. The paper found that the Nigerian armed forces have made significant achievement in the fight against Boko Haram and these groups as shown in the number of territories it has recovered from the insurgents. The Paper also found that the Nigerian armed forces do not have adequate weapons to prosecute the war against insurgents. There are also reports of a third force within and outside the armed forces that sabotage the efforts of the armed forces. This third force are politically and financially exposed persons who engage in corruption. The paper recommends adequate monitoring of these funds of the armed forces to enable them to purchase modern military equipment to fight the insurgents.

This study relied on secondary data sources and other archival documents that provided the required information for the discourse. Acute and logical analysis of these data proved that the alarming level of insecurity in Nigeria has fuelled the crime rate and terrorists’ attacks in various parts of the country, leaving unpalatable consequences for the most affected states economy and growth. To address the threat to national security and combat the increasing waves of crime, the Nigerian government must consider challenges and recommendations highlighted as part of her national policy. This paper therefore concludes that, since the journalists served as a watchdog to correct the defence sector inept activities, the inadequate funding, corrupt procurement and poor maintenance result in serious equipment and coordination deficits.

Key Words: Defence Sector, Democracy, Military, Nigeria, Corruption, Media, Journalists

Introduction

Historically, it can be inferred that the principal task of the defence sector is to defend the state against threats to its national security. The significance of defence sector is the task to primarily defend the country from foreign agents and domestic subversive elements. However, it must be observed that the defence sector is in a way not the only major security player in the complex systems of modern democratic states. In some countries, other authorities have certain security responsibilities, including the special central governmental structures, defence, foreign affairs, immigration, customs and trade, energy, transport, finance, health authorities and so on (USIC, 1996).

As mentioned above, the defence sector could also be part of the decision makers and even where it is not, it works closely with law enforcement institutions to prosecute individuals and groups who commit offences against national security (Dovydas, 1999). Therefore, this paper will inevitably touch upon certain aspects pertaining to other security structures, insofar the defence sector as a security service interacts with them.

The Nigerian defence sector no doubt has become the central concept at the confluence of security with core elements that include accountability, effectiveness, efficiency, transparency, inclusiveness, equity, and rule of law (Bryden and Chappuis 2015). That is why the defence sector has often remained an issue of great concern to the “fourth estate of the realm” of the republic. Unarguably, Nigeria in recent times has witnessed an unprecedented level of insecurity. This has made national security threat to be a major issue for the government and has prompted the senate to insist that increased budgets for the security and defence sectors to address the current security challenges are crucial in winning the war against insurgency, banditry, kidnappings, and other crimes (Jimoh et.al., 2021). To ameliorate the incidence of crime, the federal government has embarked on criminalization of terrorism by passing the Anti-Terrorism Act in 2011 (Angbulu, 2021). The government is also strengthening security agencies through the provision of security facilities and the development and broadcast of security tips in the mass media. Despite these efforts, the level of insecurity in the country is still extremely high.

Hence, Nigerians hold the view that national security architecture is not as effective as it ought to be, coming on the hills of very tangible and discernable realities: insurgency, pervasive militancy, kidnapping, piracy, banditry, herders/farmers clashes, armed robbery, ritual killings, cultism, rape, and huge numbers of internally displaced persons (IDPs) (Clifford, 2018).

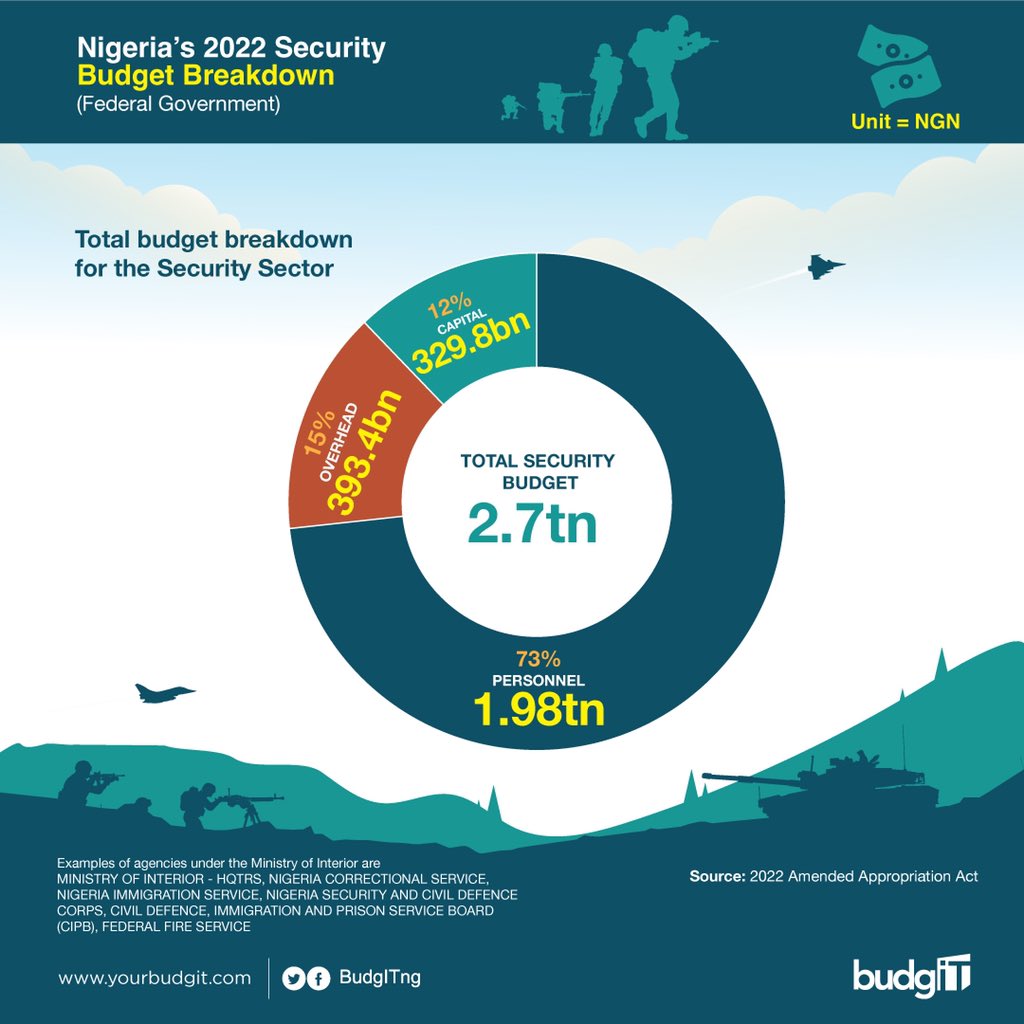

While this is true due to the current insecurity challenges spread across the country. Huge resources allocations to the defence sector ranging from statutory allocations to defence, police, civil defence and paramilitary agencies, state security, office of National Security Adviser and Security Votes, have over the years been devoted by both the Federal and State Government to enhance security and fulfill its statutory responsibility to protect Nigerian lives. Protection of life and property is the first responsibility of any government in a democratic society to protect and safeguard the lives of its citizens. That is where the public interest lies. Despite the huge budgetary allocations and spending in the defence sector, Nigeria continues to witness incessant attacks, loss of lives and property and other forms of crimes and criminality by bandits, terrorists, militants, kidnappers. Conversations have begun to emerge on the need to unravel what constitutes the defence budgets and security votes and the nature of its accountability (Otobo and Obaze, 2022).

There are suggestions for an effective citizen led oversighting mechanism to monitor defence spending and ensure accountability. It has become imperative to assess the effectiveness of past national security funding and consider governance reforms that may be required to cut waste, reduce cost of governance and redirect scarce revenue and resources towards developmental needs. The military expenditure in Nigeria continues to increase exponentially, rising from $ 697 million to $469.6 billion in 2020. In the past decade from 2008 to 2018, Nigeria allocated the sum of $16 billion for defence or 10.51% of the cumulative budget of $153 billion during that same period. $4.6 billion was allocated for the defence & security sector in 2019 and $4.6 billion in 2020. The total budget for security in 2020 constitutes 16.8% of the total budget of $27.9 billion (FES Nigeria, 2020).

It is on this note the journalists are tasked to play a watchdog role on the activities of the defence sector which include finances and budget to make them perform their roles properly. The Journalist is a human being, he studies other human creatures, report about human being and human beings are the source of his information. Journalism is a social relation. The information disseminated by the journalist could be harmful or useful depends on its contents. This is where the issue of defence sector comes in. The media transmit messages about a particular society. No one else can play this role. The information is passed across a destination to achieve a goal. The state exists for the interest of defence, public safety, public morality. The freedom of expression and the press is an aspect of national security, and it is necessary for a true democracy. The freedom of expression and the press is crucial ingredient of democracy. The greatest challenge to the mass media in Nigeria today is how to make itself relevant to the Nigerian society particularly where democracy is on trial, and national institutions are taking shape. The press ought to tread wearily and exercise discretion if it is to preserve its freedom. It is in the light of this that the paper discusses the role of journalist watchdog in the activities of the defence sector without endangering national security. The media functions as watchdog capable of blowing the whistle to call attention to serious national issues. This implies a clear recognition of the fact that the media plays a significant role on issues of national security (Ofuafor, 2008).

Conceptual Clarification

Defence Budget and Spending

Ever since the earliest pioneering work concerning the determinant factors behind the defence expenditure of nations, the existence of a demand function has been considered, derived from a social or, in some cases, individual – utility function allowing us to observe the relevance of the different explanatory factors employed. Within this context, various concepts of the defence budget and spending have been used. According to Antonio (2012), he defined defence budget and spending as a public good in most cases, whereby the demand for military spending is an indication as to how a country assigns its resources between the defence good and other goods, in relation to a set of explanatory variables (Hartley and Sandler, 2001). Folscher & Cole (2006) described the defence budget as a quantitative expression of the proposed plan of action for the attainment and optimization of defence objectives in the medium term. Le Roux (2002) stated that for defence budgets to optimize their objectives, they must begin at the lowest unit level with clear inputs, accurately determined, and cost from zero. The mandatory items to be covered are: personnel expenditure (salaries, allowances, bonuses and gratuities), administrative expenses (office supplies, transport, travel, training, study expenses), capital items such as ammunition and explosives, spares and components, construction and building, clothing amongst others), equipment (weapons, vehicles, machinery and furniture), rental of land and buildings, professional and specialist services such as consultation, outsourced services.

Nevertheless, as well as purely strategic aspects such as that mentioned above, due to responses to changes in the international scenarios the demand for defence spending has been affected by shifts in the preferences of developed societies which do not allow for major increases therein. Obviously, institutions, political parties, must respond to the demands of the median voter as a means of obtaining votes, which leads them not to make significant increases in defence spending (Dudley and Montmarquette, 1981). However, as explained by Fritz-Abmus and Zimmerman (1990), the factors that define the demand for defence spending are of three types: economic, political and military. Such diversity of aspects makes this type of analysis exceedingly difficult as, on the one hand, the heterogeneity of situations multiplies, whereby contradictory behaviour can be observed among the three aspects within a single country.

As regards the factors used for explaining defence spending, the various theoretical and empirical approaches have highlighted various aspects, depending on the time frame of the analysis. On the other hand, the organisational policies approach (bureaucratic approach) focuses on the behaviour of the public sector over time, whereby due to the complexity of the decision making process in relation to defence spending, this process leads to a significant level of “incrementalism” in expenditure; i.e. there is a certain degree of predictability thereof linked to its past history, whereby the spending of the previous year becomes the main explanatory factor behind the current year’s expenditure (Rattinger, 1975).

Within this set of analyses, income is the most widely used variable in explaining the demand for defence spending, which shows a positive relationship regarding military spending. Some authors say that security is a luxury good, since its demand increases more quickly than income (Dudley and Montmarquette, 1981). Moreover, it has been observed that larger countries spend a proportionally greater amount on defence (Murdoch and Sandler, 1984), although this is only true when developed countries are compared.

However, one criticism of this result arises from the proposal that a country will spend more on defence depending on internal factors as well as its international involvement and commitment, not only in military terms but also economic and political based on its desire to maintain a specific position on the international stage, whether leadership or other. Thus, both strategic and international influences and conditioning factors determine a major proportion of defence spending, regardless of population volume (Smith, 1989).

For this paper, external threats would have to be incorporated into the model, as they affect not only an individual country, but also alter burden sharing among allied nations, leading to free riderbehaviour arising from a response in which a country’s own expenditure is replaced by that of its allies (Okamura, 1991). Some literature based on individual countries shows that both the proximity of neighbouring countries with which it has disputes as in the case of Greece and Turkey, as described by Kollias (2004) and the geopolitical situation within a context of regional conflict tend to increase defence spending (Sandler and Murdoch, 2000). The clearest example of this is the fight against insurgency in Nigeria.

Read also: Special Report: Tracking Nigerian military’s commercial ventures?

The main difficulty regarding this aspect is the gauging of threats. In some cases, the defence spending of the other party has been used to gauge the threat level (Smith, 1989), while in others it is the proportion of havoc wrecked by unfriendly neighbours (Sandler and Forbes, 1980). Obviously, neither approach is completely satisfactory, but they address an issue which is extremely hard to quantify. Thus, the existence of ongoing conflicts is clearly a major factor in explaining the concept of defence budget and spending.

Corruption in Budget and Spendings in Nigerian Defence Sector

The cumulative number of resources devoted to security in Nigeria, remains opaque. The funding of the military, especially the ongoing decade of counter insurgency operation, is generating heated controversy especially over who manages the money allocated to the Ministry as both the Ministry of defence (MOD) and the Office of the National Security Adviser (ONSA) have repeatedly denied managing the money. While the former has washed its hands off the expenditure of the military, the ONSA, too, has done the same but some officials of the former have faulted the ONSA’s claim. In view of the above, critical sections of the populace have been asking questions about the funding of the ongoing counter insurgency operation which involves the military and all the security agencies such as the Defence Intelligence Agency (DIA), the National Intelligence Agency (NIA) and the Department of the State Security Services (DSS) (Eme et al, 2019). The controversy came to the open when the Leadership Weekend in 2014, in a story published in one of its editions quoted a ministry source alleging that the ministry of defence was not involved in the funding of the operation.

According to Eme et al. (2019), an MOD official, who corroborated the story, explained that the office of the National Security Adviser (ONSA) is overseeing the funding of the counter insurgency operation. According to him, the MOD’s involvement in the funding of the military is on paper, not real. It is on paper that the military receives its fund through the MOD that may have to do with the overheads but when you are talking of the real funding of the ongoing counter insurgency operation, the vote is allocated to the Office on the National Security Adviser. Therefore, the ministry is not aware of the purchase of any ammunition or any other thing that is needed for the operation (Eme et al, 2019).

In the area of purchasing, journalists had posed the puzzleof who oversees the due process, verification, qualities, standardization? By implication, ministries of interior, defence, and the police affairs are not directly involved in their capital expenditure, and the question is, who accounts for their purchases (Tell Magazine, 2014). The point in emphasis is that each of these ministries not only the MOD should be deeply involved in all their transactions for accountability.

Sadly, since the war against insurgency started in 2009, there is no year the military did not get a chunk of the national budget. Most times, the Defence budget is higher than even education or works, essentially because Nigeria value security. But the country has not got quite a good deal in the issues of security. So, when it got clear that the regular budgetary allocations were not enough to tackle the rising cases of insecurity, the decision to pull out $1 billion from the Excess Crude Account (ECA) was taken in 2018 prior to 2019 general elections. It was argued then that with the $1bn, more arms and ammunition would be bought to combat and over run the terrorists (Eddy, 2022). However, how the money was being appropriated and disbursed is still enmeshed in controversy and shrouded in secrecy till date. It was a common knowledge that the former service chiefs once complained of having not received the said $1bn at a time, while pointing accusing fingers at the National Security Adviser (NSA), Maj-Gen. Babagana Monguno (rtd) who in turn directed it back to the military services, MOD, and Ministry of Finance and Budget Planning. Report, however, had it that when the $1 billion was eventually released, in tranches, the public was no longer carried along. The last check point is therefore the National Assembly which exercises oversight functions on every aspect of governance, including the military. That explains why in recent times, the National Assembly had to invite (and later summon) the service chiefs to explain some of the fog surrounding the utilization of the $1billion. The trigger to this inquest must have been the alarm raised by Monguno that the sum of $1billion was missing because neither the money nor the arms can be seen. In an interview he granted BBC Hausa service, Monguno posited that,

“The president has done his best by ensuring that he released exorbitant funds for the procurement of weapons which are yet to be procured, they are not there. Now the president has employed new hands that might come with innovative ideas. I am not saying that those that have retired have stolen the funds, no. But the funds might have been used in other ways unknown to anybody at present. Mr. President is going to investigate those funds. As we are talking with you at present, the state governors, the Governors Forum have started raising questions in that direction. $1 billion has been released, that and that has been released, and nothing seem to be changing” (This Day, 2022).

The tongue-in-cheek allegation of the NSA is that the money meant for arms is missing, hence the emphasis on Mr. President’s determination to investigate the issue. But the President’s spokesperson, Mallam Garba Shehu, dismissed the allegation that some money meant for arms purchase were missing. He explained that not all the arms procured by the former service chiefs have arrived the country. He noted that the sum of $536 million was paid directly “government-to-government” to the government of the United States of America for the supply of some arms. He noted further that the biggest catché of arms was soon come from the United Arab Emirates (UAE). It should be recalled how the sum of N3billion was traced to the accounts of Mrs Lara Amosu, the wife of former Chief of Air Staff, Air Marshal Adesola Amosu, and even another $1 million found in a newly constructed septic tank in their Badagry country home. How can one forget also how the former Chief of Defence Staff, Alex Badeh who was said to have stolen N558 million and later converted same to $20 million. He was being tried, after one of his seized properties was gifted to Voice of Nigeria. He was later shot and killed on the Abuja-Keffi Road by assailants. So, it is not enough believing the explanations of Mallam Garba Shehu, especially as the NSA do not know what Shehu is explaining.

Conflict entrepreneurs within the hierarchy of military leadership and the ministries, departments and agencies in the security sector apparently use military funds meant for counter-terrorism operations to enrich themselves. Military spending is usually not audited due to its sensitive nature. The secrecy that surrounds it encourages misappropriation. Examples include the probe into the alleged diversion of US$2.1 billion meant for arms procurement by the Office of the National Security Adviser, and another N3.9 billion by the office of the Chief of Defence Staff, both in 2015 (ISS, 2020).

The findings of Transparency International (2017), BudgIT (2018) and Compendium of Arms Trade Corruption (2019) were also able to establish that the military is being poorly funded, some disagree, and that the money passed by the National Assembly is being diverted or withhold by the Presidency. They even found out that military purchases some refurbished ammunition because of poor funding or mismanaging of the money allocated to it and that most of the contractor’s given jobs are recommended by the National Assembly members and the officials of the presidency and the ruling party (CATC, 2019).

According to a Transparency International report, a network of Nigerian military chiefs, politicians, and contractors worked together to steal more than N3.1 trillion through arms procurement contracts between 2008 and 2017. These contracts would fetch the military chiefs and a couple of other agents N3 billion. Here are some of the top defence and security procurement related scandals in recent memory as documented by PREMIUM TIMES (2017), TI (2017) and Compendium of Arms Trade Corruption (2019). These are not farfetched as they are highlighted in the table below:

| S/N | Subject/Headline | Commentary | Budgetary Status | Investigative Status | Remarks |

| 01 | $1b ECA Fund for Counter-Insurgency Operations (2018-2021) | President Muhammadu Buhari-led Federal Government of Nigeria, had prior to 2019 elections in which he was seeking his second term bid, took out $1 billion from the country’s Excess Crude Account (ECA). This money was taken despite fierce reservations from the opposition elements, especially the Peoples Democratic Party (PDP) that had expressed concern that the underlying reason for the money was for the re-election bid of Buhari and assist the ruling All Progressive Congress (APC) retain power. Countering these fears, the government had argued then that with the $1bn, more arms and ammunition would be bought to combat and over run the terrorists. However, these concerns that the money could be misappropriated came to reality when the National Security Adviser (NSA), Maj-Gen. Babagana Monguno (rtd), raised the alarm that the sum of $1billion was missing because neither the money nor the arms can be seen. That, perhaps, explains why in recent times, the National Assembly had to invite (and later summon) the service chiefs to explain some of the fog surrounding the utilization of the $1billion. | This was an extra-budgetary/off-budget allocation, taken outside the approval of the nation. Even though the President later sought Legislative nod but this was just a mere formality as the money has been withdrawn without under Buhari’s directives. | Media: There were some media reports but with limited inroads and success at investigation. It was difficult to track the money and trace who is responsible for its appropriation between ONSA, MOD and Federal Ministry of Finance. Justice: There was no court case as no official, institution or agency was held responsible. | Current Status: How the money was being appropriated and disbursed is still enmeshed in controversy and shrouded in secrecy till date. Report, however, had it that when the $1 billion was eventually released, perhaps in tranches, the public was no longer carried along. Consequences: No one was sacked, suspended or punished. All the key actors are either still in government or retired honourably. |

| 02 | NIA Ikoyi Scandal– Defence cash stashed in defence chief’s wife’s apartment (2017-2019) | April 12, 2017, Whistleblowers led the Economic and Financial Crimes Commission to a house in upscale Ikoyi where $43.4 million was kept. The National Intelligence Agency (NIA), Director-General, Mr. Ayodele Oke, later claimed the money was meant for undisclosed special security and defence projects. | This was completely outside any budgetary allocation as National Assembly were completely in the dark about the money. | Media: There was initial media blitz, which later died down as it was difficult to investigate further. The challenge is that the media only reported what the authorities fed them. Justice: There was no court case in whatever form. Investigations are still going on and the real motive for keeping the fund in that location remained unclear. | Current Status: The investigation outcome remains inconclusive till date. Consequence: The then Nigeria’s Intelligence Chief, Ayodele Oke, was suspended by the Presidential Panel but he later retired with full benefits without trial. No one else was punished. |

| 03 | Dasuki armsgate (2012-2021) | At the center of the web of corruption is Col. (rtd.) Sambo Dasuki, Jonathan’s National Security Advisor(NSA) from March 2012 to March 2015. Dasuki effectively controlled military procurement during hisperiod in office with no supervision and virtually no input from the Ministry of Defence. The transactionsinvolved in the Armsgate scandal took place under the rule of the People’s Democratic Party (PDP)government of Presidents Umaru Yar’Adua, who ruled from 2007 until his death in 2010, and Goodluck Jonathan, Yar’Adua’s vice president, who took over in 2007 and subsequently won reelection in 2011. The Armsgate scandal broke in 2015 when a government-appointed independent investigation revealed a series of arms deals in which Ministry of Defense funds were transferred to private accounts and no arms were procured. The deals allegedly benefited a number of senior military officers, politicians, government officials, and businessmen, and their families. Most of these companies were awarded fake contracts for equipment that was never delivered. Largest contract was for 4 Alpha jets and 12 helicopters, also never delivered (TI, 2017, p. 11). | Rather than corruption, these deals are more accurately classified as theft. The scandal involves the alleged theft of at least USD 2.1 billion, and possibly as much as USD 15 billion of extra-budgetary funds between 2007 and 2015 intended for weaponry to aid the government’s efforts to defeat the insurgent group, Boko Haram. | Media: As always, the case in this kind of corruption scandal, there was extensive media coverage but the information mostly relied on what the EFCC, DSS and government officials reeled out. There were no substantive findings outside this. Justice: Col. Dasuki and other suspects were arrested and tried, but after few years of court trial without any legally binding evidence, they were freed (as there was none since it was extra budgetary expenditure). | Current Status: After refusing to obey the court order to grant him bail on four different occasions, Dasuki was finally released on December 24, 2019. Nothing has been heard of the case until today. Consequences: Some individuals and companies that benefited from the funds were compelled to voluntarily forfeit or were also forced to do so through the court order. Apart from this, no one has been duly convicted and jailed by the court of competent jurisdiction. |

| 04 | Cash in bullion vans for Special Services (2014-2015) | Late 2014 to early 2015 Cash withdrawal from CBN using two bullion vans Former President Goodluck Jonathan authorised the withdrawal of N67.2 billion in cash from the Central Bank of Nigeria between November 2014 and February 2015 for “special services,” linked to defence and security operations. | This is a classic example of extra-budgetary fund shielded under the amorphous “Security Votes”. | Media: Apart from the few media reports, there was no further investigation into this. Justice: No one was tried or held responsible. It was rather hushed in the name of “national security and defence”. | Current Status: The case is rarely mentioned either in the media or court. Consequences: The apex Bank chief, Mr. Godwin Emefiele, is still at the helm, while President Jonathan and most of his then security chiefs remain untouched. |

| 05 | Cash for Black market Arms in South Africa (2014-2015) | September 5, 2014, the South African border authorities seized $9.3 million belonging to Nigeria from two Nigerians and an Israeli who arrived the country in a private jet owned by a pastor, Ayo Oritsejafor. Customs officers discovered the money stashed in three suitcases after the suitcases were put through airport scanners. The Nigerian government later admitted the money was meant for the procurement of black-market arms for the Nigerian military. | This funded was not budgeted for but part of the nebulous tag: “Security Votes”. | Media: This received extensive media report with the Nigerian government justifying why it has to use such method, while blaming the United States for blocking its efforts to acquire arms for counter-terrorism and counter-insurgency operations against Boko Haram terrorists in the North East under the Leahy Law. Justice: There was no court trial. | Current Status: This was buried under the bigger “Dasukigate Arms Scandal”. Consequences: No one is known to have faced any consequences. The key actors are still at large. |

| 06 | Urgent N7 billion Boko Haram funds missing (2015) | January 2015,Nurudeen Mohammed, the then Minister of State Foreign Affairs, requested N7 billion to urgently fundoperations of the Multinational Joint Task Force in the Lake Chad Basin. The funds were released to theNational Security Adviser. It is unclear how the money was used. Officials say most were traced tocompanies that had no business with the Task Force. One and a half billion naira was withdrawn in cash. | This was an extra-budgetary/off-budget expenditure. | Media: Few media reports, which fizzled out under the bigger “Dasukigate Arms Scandal”. Justice: No one was indicted or jailed. | Current Status: The “Armsgate Trial” has been overtaken by other events and no longer under the legal rather of the government. Consequences: The key actors are free and undaunted. |

| 07 | N2 billion grew wings from the office of the National Security Adviser (2013) | May 13, 2013, the Nigerian government released N1.35 billion to re-stock ammunition for OPERATION BOYONA, aimed at dislodging terrorist camps along the borders with Cameroon, Chad, and Niger. Two months later, the National Security Adviser, Sambo Dasuki, requested and got approval for additional N2 billion. It does appear neither the Defence Headquarters nor the soldiers on the battlefield benefited from the second cash released to the NSA. The money is believed to have disappeared; an allegation Mr. Dasuki is denied. | This was under extra-budgetary/off-budget provision | Media: Received limited media reportage without sustained follow-up reports Justice: There was no conviction | Current Status: Dasuki denied the ellagtion. Consequences: No one has been punished in whatever way. |

| 08 | The Shaldag contracts (2010) | 2010, the Shaldag contract is one of the deals that paved the way for a regime of kleptocracy in the Nigerian defence sector, and the emergence of a gang that has grown to be more powerful than elected regimes. The 2010 deal saw an Israeli shipbuilder, Israeli Shipyards, win a $25 million contract to supply Nigerian Navy with two fast assault boats. Their market value at the time was estimated to be $5 million each. | Budget inflation | Media: Limited media report and no substantive further investigation. Justice: There was trial of suspects in Israel but none in Nigeria | Current Status: Nigeria, reportedly lost $15 million in the deal. It is however, unclear how the $15 million excess was shared between everyone involved. Consequences: The Israeli police have established that the middleman, Amit Sade, received $1.47 million in what is now termed brokerage fee. Three people are facing trial in Israel over this deal. |

| 09 | Progress Limited (2010) | April 29, 2005 to October 19, 2010, the ministry of defence gifted two purchase contracts to Progress Limited for the supply of 42 units of BTR-3U Armoured Personnel Carriers and spare parts for the Nigerian Army without documented contract or agreements. There was no cost negotiation between the two parties. Two years later, 26 used APCs were delivered but they broke down almost immediately after they were deployed for peacekeeping operations in Sudan. | Off-Budget/Extra-budgetary | Media: Limited media report. Justice: There was no trial. | Current Status: There is no substantive effort to try or hold anyone accountable. Consequences: The key actors are free and unperturbed. |

| 10 | The Amit Sade contracts | October 6, 2008, on that day, Amit Sade, an Israeli contractor who does not own any arms manufacturing business working out of Nigeria was gifted a combined N5.2 billion contract. The first was to deliver “assorted ammunition” at the cost of N2.1 billion. The other was to supply “20 units of K-38 twin hull boats” at the cost of N3.1 billion. He was paid 95 percent for the ammunition. He delivered a 63 per cent worth. On the K38 boats, he was paid 80 per cent; he delivered only 40 per cent. In the last decade, Mr. Sade, records show, was gifted another six heavy-weight military contracts worth N6.721 billion. He is alleged to have failed to deliver on any of them. He could not be reached to comment for further investigation. He did not reply inquiries, and his current location remains unknown. | Defence Budget | Media: Limited Justice: No trial | Current Status: No effort by the government to pursue and sustain investigation into the case. Consequences: The principal actor is still at large. |

Challenges in tracking and monitoring the Defence Sector Budget

Security agencies often hide under the guise that journalists and media have breached the security. The media as a social institution with a long history of fighting injustice against the establishment and defending the people’s right to know and hold their leaders to judicious account of resources has the right to interrogate any aspect of government, including the military and the defence sector. However, several challenges are highlighted and discussed below:

Extra-Budgetary/Budget Allocations: One of the most challenging facts about Nigeria’s defence and security sector is that it relies on extra-budgetary means to execute most of its procurement. This means that most of the fundings and expenditure are not provided, approved and oversighted by the National Assembly. For the fact that these monies remain outside the scope of legislative approval means that it would be almost impossible to track and prosecute. Majority of the Defence and Security fund scandals exposed and being reported in the media emanates from this. This is why it was proving difficult to get any conviction in the law court.

Lack of harmonised procurement authority: As earlier cited in the course of this paper, the heated controversy especially over who manages the money allocated to the Defence Sector between the MOD and the ONSA hampers proper accountability and the ability to effectively monitor disbursements. In this regard especially in the area of purchasing and defence procurement, journalists had posed the puzzleof who oversees the due process, verification, qualities, standardization? But there is no answer yet.

Porous Access to Credible Information by Journalist: Official information is protected through the Official Secret Act which prohibit the collection, possession, or dissemination of official information and state secrets (Yalwa and Pali, 2019). The National Assembly passed the Freedom of Information Act, and it became law in 2011 but its use has not become common and officials, especially those guiding defence and military secrets, are still beholden to the days of Official Secret Act.

Obnoxious Decrees: The press in Nigeria is still being checkmated by various previous military decrees. These include offensive publication (proscription) Decree No.35 of 1993; State Security (Detention of Persons) Decree No.2 of 1984 under which journalists can be detained and held incommunicado for security reasons; The treason and other offences (Special Military Tribunal) Decree No.1 of 1996; as well as The Constitution (suspension and modification) Decree No.107 of 1993 which annuls a citizen’s right to public apology or compensation, if he was unjustly or unlawfully detained. (SMT, 1996, p.100)

Secrecy and confidentiality: Defence sector stakeholders, particularly military forces, have a strong inclination towards secrecy. The military and other security and intelligence actors often try to limit the amount and quality of the information they release. Some part of military planning and activity is compromised if it becomes publicly available, which justifies a certain degree of confidentiality in some areas. However, secrecy requirements are often used as pretext t to hide unlawful activities.

Trust deficit between media and defence sector: The media is essential for establishing and maintaining public support for any military operation. Tension between institutions and agencies with overlapping responsibility is nothing new in public life. Restricted access enforced by the military as a duty to protect information, prevents journalists from fulfilling their duties to independently verify facts. When this happens, trust becomes a significant issue, and the military is often suspected of hiding the truth. The problem is compounded when the issues involve politics (Momodu, 2022).

Corruption in the defence and security sector: Reporting issues of corruption within the defence and security sector is an enormous task because they often hide under the oath of secrecy in matters concerning defence budgeting and expenditures. The closeness of the security sector often allows the parties in power to easily abuse their positions in these sectors. Indeed, the ability to classify security budgets and funding provides an opportunity for various abuses.

In addition, organizational culture among the defence sector carries a considerable risk of solidarity among the officers and men to the extent of covering up corrupt practices of colleagues, despite being aware about the case.

Legal Limitations: Justifiability of some aspect of the constitution. For instance, Chapter 2 which 1999 Constitution gives Journalists the power to ensure that government implement policies is not justiciable under the law. Also, the cybercrime Law of 2015 prohibit individual of repeatedly use of electronic communication to harass, intimidate, and frighten a person. Section 24, 1(A and B); 2(A, B and Ci and Cii); 3(A and B), 4, 5 and 6 punishes anyone convicted of that (Owonikoko, 2022).

Overcoming the challenges: options and recommendations

Stop or Curtail Extra-Budgetary/Off-Budget Allocations: At the top is the need to either scrap the extra-budgetary allocation system or curtail it drastically. Or done in such a way that it is subjected to the legislative approval and oversight so that it could also be legally and constitutionally monitored, tracked and adjudicated on.

Need for harmonised defence procurement authority: There is need to ensure a specified channel of authority on who is responsible for the disbursement of funds for defence and security expenditure. This is to ensure transparency, accountability and responsibility.

Develop a unified anti-corruption strategy for the defence sector: Consideration should be given to engaging all levels of staff and grounding anti-corruption effortsin an analysis of the main opportunities, causes and enablers of corruption. Armed with this intelligence,targeted reforms capable of increasing anti-corruption controls could be developed into apractical action plan tailored to address these challenges.Establishing a high-level leadership steering committee, or “Reform Board,” responsible forsetting direction would help ensure the reform process develops momentum.This Reform Board could be comprised of senior leadership of the Ministry of Defence (MoD),the Office of the National Security Advisor (ONSA), senior military officials, and key functional personnel who have important roles in ensuring integrity in the ministry. President Buhari couldsignal endorsement by inviting expert international and domestic technical experts to contribute.

Extend public access to defence and security information: Recent amendments to the Public Procurement Act are an important advance in the fight against defence corruption, but they will have limited impact without corresponding amendments to the Freedom of Information Act. (“WEAPONISING TRANSPARENCY – Transparency International Defence & Security”) Also introduce Guidelines for separating confidential from non-confidential information, such as the Global Principles on National Security and the Right to Information. The Tshwane Principles would help limit abuses by setting out what information on budgets and procurements could be disclosed. This would help create meaningful transparency in defence budgets and allow for more effective oversight by the organisations mandated to perform this role. It is vital that the Ministry of Defence provide the Senate and the public with timely, detailed, and comprehensive information on the MOD and the ONSA budgets, including how much is allocated to secret spending.

Monitor confidential procurements: For genuinely confidential procurements, a separate legal procedure could be designed allowingfor monitoring by a confidential senate committee and a unit with suitable security clearancewithin the Bureau for Public Procurement (BPP). If it is so important for national security that aproportion of the procurement budget remains secret, then it should be equally important thatthis portion of the budget is spent effectively. The only way to ensure this, is to put in placeeffective oversight structures. There is no need to wait for a legislative amendment; militaryservice chiefs and the Attorney General have sufficient legal powers to issue clarifying interimguidelines.

Establishing a procedure for confidential procurements and thereby protecting national security would enable Nigeria to extend the commitments made by President Buhari at the 2016 London Anti-corruption Summit to the defence sector. These commitments included ‘ensuring transparency of ownership in public contracting, implementing Open Contracting Principles, and preventing corrupt bidders from winning contracts’ (Anti-corruption summit, 2016). Prohibiting the award of contracts to companies that do not fully disclose their beneficial ownership could be a positive move towards tackling ‘briefcase companies’ shell companies that only exist on paper – and cleaning up defence contracting.

Civil society and the media are powerful monitors, and the Procurement Act empowers both to monitor tender awards. Guidelines for non-classification would enable civil society to extend its monitoring to the defence sector, thereby realising a function originally envisaged in the legislation.

Regulate secretive security votes: There is no oversight of ‘security vote’ spending. Widely perceived as one of the most durableforms of corruption in Nigeria today, security votes should be abolished or strictly regulated. ThePresident, state level governors or the Attorney General could work with civil society and theNational Assembly to publish guidelines that allow for proper scrutiny of how such funds arebudgeted, spent, and monitored. Declassifying how the security vote funds have been spent,after a two-year information embargo, could also enable citizen oversight.

Extend whistle-blower protection: Implemented just a few months ago, the whistle-blower policy is already positively contributingto law enforcement efforts. More whistle-blowers would be encouraged to come forward withevidence of defence sector corruption with the enactment of a whistle-blower protection law thatincludes citizens and private sector employees.2 Alternatively the Attorney General could issueguidelines clarifying that the Freedom of Information Act 2011 protections for whistle-blowersalso apply to defence and security sector whistle-blowers.

Conclusion

Nigeria’s defence spending raises several critical concerns. The paradox of course is that the more government spends on defence, the more insecure Nigerians feel. Travelling inside the country has become so perilous that it is now advisable to get a security report of all towns and villages on our way before setting out. The non- investment of previous administrations on the security sub-sector has both internal and international security implications for Nigeria and her population. Since the journalists served as a watchdog to correct the defence sector inept activities, this paper posits that inadequate funding, corrupt procurement and poor maintenance result in serious equipment and logistics deficits needs to be investigated by their media in order to properly inform the public. This is in fulfilment of their role as enshrined in Chapter II Section 22 of the 199 Constitution of Nigeria, which states the media shall always…” uphold the responsibility and accountability of the government to the people; and …shall be a watchdog over the excesses of government and shall ensure that government delivers its promises to the people. The government on the other hand shall ensure that the press informs the people about its programmes and actions.” However, the paper revealed that constitutional lacuna and gaps in decrees further aided security personnel in engaging in corrupt practices through budget allocation and spending. These fallouts are because of corruption in the defence sector which this paper examined.

Among the findings is the fact that although bribery can occur in arms procurement anywhere, the problem can be far worse in countries where military spending and decision-making lacks transparency, accountability, monitoring, and oversight institutions are weak. In such cases, corruption can go well beyond a 10% commission on the sales price being paid in bribes and can encompass wholesale embezzlement or stealing as it is more plainly called in Nigeria. In the Nigerian Armsgate scandals, for instance, former President Goodluck Jonathan gave his National Security Advisor Sambo Dasuki unchecked control over the country’s military procurement budget, including both on- and off budget spending, with no oversight. Dasuki proceeded to loot at least $2 billion to his political, military, business cronies using fake procurement contracts for which no equipment was ever delivered. Unfortunately, media tracking, investigation, and reportage of the defence sector, especially the defence budget procurement and the corruption therein. This is due to some inherent barriers as highlighted by this paper, which also proffered practical solutions.

Reference

Abdu, H (2013) When Protectors Become Aggressors: Conflict and Security Sector Governance in Nigeria in Mustapha A, R (2013) (ed.), Conflicts and Security Governance in West Africa, Abuja, Altus Global Alliance.

Angbulu, S. (2021, November 25). Kidnapping: Buhari orders increased surveillance, patrol on Abuja-Kaduna Road, Punch, Available at: https://punchng.com/kidnapping-buhari-orders-increased-surveillance-patrol-on-abuja Kaduna Road/ [Accessed 8 January 2022].

Bryden, A and Chappuis, F. 2015. Introduction: Understanding Security Sector Governance Dynamics in West Africa. In: Bryden, A and Chappuis, F (eds.) Learning from West African Experiences in Security Sector Governance, Pp. 1–18. London: Ubiquity Press. DOI: http://dx.doi.org/10.5334/bau.a. License: CC-BY 4.0 SSG-2

BudgIT (2018), Proposed Security Budget: A Fiscal Overview, Lagos: BudgIT

Chayes, S. (2015), Thieves of State: Why Corruption Threatens Global Security, New York: W.W. Norton.

Chayes, S. (2016), Corruption and Terrorism: The Causal Link, Getty http://carnegieendowment.org/2016/05/12/corruption-and-terrorism-causal-link-pub-63568 May 12, 2016.

Church, C. (2007), “Thought Piece: Peace building and Corruption: How may they collide?” The Nexus: Corruption, Conflict, & Peace building Colloquium. Boston: The Fletcher School, Tufts University.

Country statement from Nigeria, “London Anti-Corruption Summit May 2016”, https://www.gov.uk/government/uploads/system/uploads/attachment_data/file/523799/NIGERIA_FINAL_COUNTRY_STATEMENT-UK_SUMMIT.pdf

Daily Independent Editorial (2014), Defense and security sector (2) Wednesday 04, June.

Dasukigate: Here is a breakdown of the alleged misappropriation of $2.1 billion by Dasuki and others”, Ventures Africa, 14 December 2015, https://venturesafrica.com/ dasukigate- here-is-abreakdown-of-the-misappropriation-of-2-1-bn-meantfor-arms-deal-by-dasuki-and-others/ and

“EFCC publishes names of military officers on trial” News 24, 4 July 2016.

Dixon, K, Watson, & Raymond, G (2017), Weaponising Transparency: Defense Procurement Reform as a Counterterrorism Strategy in Nigeria, Lagos; Transparency International & Civil SocietyLegislative Advocacy Centre.

Falana, F. (2014), “How Courts Frustrate Corruption Cases”, The Nation, Thursday, April 24, Pp. 40-41.

International Crisis Group (2016), Nigeria: The Challenge of Military Reform, 6 June, Pp1-18.

Ihejirika, A.O (2011), “Roles, Challenges and Future Perspectives of the Nigerian Army”, National Defence College News Magazine, Abuja.

Jimoh, A. O. Okwe, M. Abuh, A. Daka, T andAfolabi, A. (The Guardian, 21 June 2021), Worsening insecurity: Seven-year N8tr defence spending, freshN762b loan worry Senate, CSOs, [online] Available at: https://guardian.ng/news/worsening-insecurity-seven-year-n8tr-defence-spending-fresh-n762b-loan-worry-senate-csos/ 9, accessed 4 November 2022.

Lawal, T, Victor, O.K. (2012). „Combating Corruption in Nigeria‟, International Journal of Academic Research in Economic and Management Sciences, 1(4), 1-7.

Momodu, J. A. (2022)., “Shrinking Civic Space and Challenges to Media Coverage of the Defence and Security Sector in Nigeria”, Centre for Peace and Security Studies, Modibbo Adama University, Yola.

“Nigeria’s vice president says $15 billion stolen in arms procurement fraud”, Reuters, 3 May 2016, http://in.reuters.com/article/nigeria-corruption-idINKCN0XT1UK.

“Nigeria’s Dasuki arrested over $2bn arms fraud”, BBC News, 1 December 2015,

http://www.bbc.co.uk/news/world-africa-34973872.http://www.news24.com.ng/

National/News/efcc-publishes-names-of-military-officers-on-trial-20160704.

Obi, P. (2017), “Corruption in Military Dangerous, Divisive, Wasteful, Fuels Insurgency …”, August 11, 2017, https://www.thisdaylive.com ›

Owete, F. (2014), “Falana Slams Nigeria’s Senior Lawyers, Judges, accuses them of Frustrating

corruption trials,” Premium Times, Friday, April 18, P 12.

Olukotun A. Repressive State and Resurgent Media Under Nigeria’s Military Dictatorship, 1988-98. Ibadan, College Press and Publishers Ltd,2005.

Premium Times, “Plundering the armoury,” 11 January 2013.

“Presidency 2015: War of the godfathers”, National Daily, 16 February 2015,

http://nationaldailyng.com/test/index.php/news/latest-news/2736-presidency-2015-war-ofgodfathers.

Owonikoko, S. B. (2022), “Instruments and Policies Enhancing/Inhibiting Effective Journalism in Nigeria”, Centre for Peace and Security Studies, Modibbo Adama University, Yola.

Smith, D. J. (2007), A Culture of Corruption: Everyday Deception and Popular Discontent in Nigeria. Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press.

Sunday Punch (2008), “How Nigerian army officers sold weapons to militants”, 20 January

The Federal Government of Nigeria (2007b). The Public Procurement Act 2007.

The 1999 Constitution of Federal Republic of Nigeria as Amended 2010.

Transparency International (Defense & Security), Watchdogs? (2013), The quality of legislative oversight of Defense in 82 countries, September 2013, http://ti-Defense.org/wpcontent/uploads/2016/03/Watchdogs-low.pdf.

The Source (2007), “The utmost betrayal” “More startling revelations on missing military arms”, 19 November.

Udoudo A. & Asak (2008). ‘The Nigerian Press and National Crisis.’ Gombe, Paper Presented at the 53rd Annual Congress of the Historical Society of Nigeria (HSN), Gombe State University, Gombe, 13th-15th October.

Wali A. (2012). Press Freedom and National Security: A Study in the Dynamics of Journalists and Security Agents Relationship in Nigeria. Open Press Ltd, Zaria.

http://www.cleen.org/Conflicts%20and%20Security%20Governance%20in%20West%20Africa.pdf

https://www.thisdaylive.com/index.php/2021/04/02/1bn-arms-deal-what-are-the-soldiers-hiding

[…] Also read: Containing the challenges of monitoring and tracking defence budget and spending in Nigeria […]