By Prof. Freedom C. Onuoha and Dr Kamal-Deen Ali

Piracy in the Gulf of Guinea

The Gulf of Guinea is one of the most important regions of the world because of its enormous endowment with strategic mineral and marine resources, critical to livelihood of coastal communities and economic mainstay of states in the region. Encompassing 17 countries from Senegal to Angola, the Gulf of Guinea’s maritime space is also a key hub of commercial maritime activities such as export of hydrocarbon resources and import of manufactured goods and food items, among others.

Over the past decade, there is growing awareness that the vast resources and potential of the Gulf of Guinea are being eroded by widespread criminality, resulting in huge financial losses, divestment, dwindling economic prospects, and political instability. The prevalent crimes in the region’s maritime domain include illegal arms and drug trafficking, piracy and armed robbery at sea, illegal oil bunkering, crude oil theft, human trafficking, human smuggling, maritime pollution, illegal, unreported and unregulated (IUU) fishing, illegal dumping of toxic waste, maritime terrorism and hostage taking and vandalism of offshore oil infrastructure.

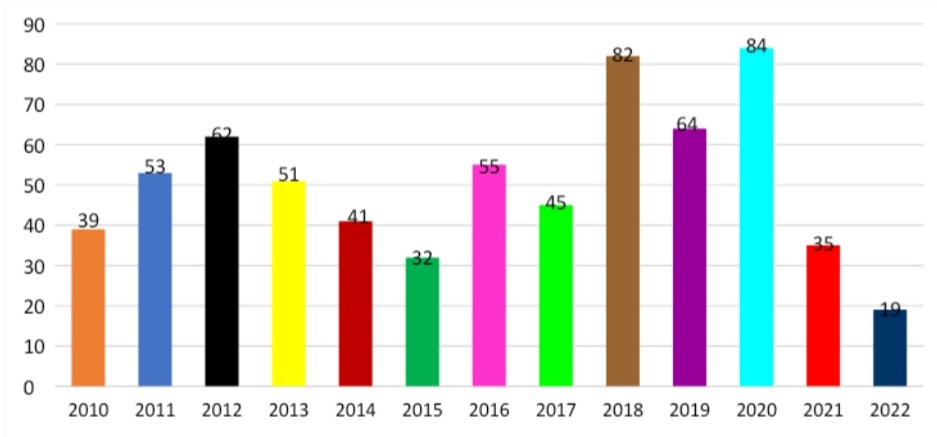

Of critical concern has been the surge in the frequency, sophistication and expansion of piracy in the region, particularly since 2011. The dynamics of piracy in the Gulf of Guinea has been phenomenal. Pirate attacks in the region have fluctuated with a total of 662 incidents reported in the region between 2010 and 2022, according to figures obtained from the International Maritime Bureau (IMB). As shown in Figure 1, the highest incident took place in 2020 when the region witnessed 84 attacks, demonstrating the frightening dimension piracy has assumed. A large percentage (47%) of the attacks took place within Nigeria’s maritime domain, especially the oil-rich Niger Delta where several pirate action groups control the highly organised criminal enterprise.

Figure 1: Map showing the Gulf Guinea including the Bights of Benin and Bonny

Source: Wikipedia

Figure 2: Piracy Incidents in the Gulf of Guinea, 2010 -2022

Source: Authors compilation from IMB Report for the years

Summary of the Threat Profile

Within the period, piracy witnessed an expansion in the range of attacks, deployment of sophisticated weapons and target selection (Figure 2). CEMLAWS Africa’s brief in 2020 sheds light on the threat dynamics, trends and increasing risks. From the use of machetes, knives, pistols and other crude tools, pirates graduated to the deployment of very sophisticated weapons such as AK-47s, M-16s, rifle grenades and Rocket Propelled Grenades (RPGs). Furthermore, prior to 2013, piracy in the region was limited to coastal areas less than 30 nautical miles from shore. In recent years, however, they have honed their navigational ability which has enhanced their capacity to extend their reach even farther offshore. In July 2020, for instance, pirates boarded a product tanker, MT Curacao Trader, approximately 210 miles off the coast of Benin and abducted some 13 crew members.

Concerning target selection, the trajectory of piracy has evolved from maritime mugging, through petro-piracy to maritime kidnapping of crewmen (mainly expatriate) for ransom. In 2019, for instance, about 151 expatriates were abducted, compared to 116 in 2018, 69 in 2017 and 38 in 2016. By the same token, official report shows that of the 85 seafarers kidnapped from their vessels and held for ransom in 2020, 80 were taken in 14 attacks reported off Nigeria, Benin, Gabon, Equatorial Guinea and Ghana coastal areas.

Figure 2: Piracy Dynamics and Threat Profile

Source: CEMLAWS Africa, Depicting key elements of the Piracy Profile as at 2020

Global and Regional Action

Understandably, the trend and threat of piracy and other transnational organised crimes in the Gulf of Guinea maritime domain elicited concerted responses from global, extra-regional, regional and national authorities towards mitigating maritime insecurity in the region. At the global multilateral level, the United Nations through Security Council Resolutions (UNSCR) 2018 (2011), 2039 (2012) and 2634 (2022) have sought to shape and inspire regional and international responses to the threat of piracy. In particular, UNSCRs 2018 and 2039 provided member-states of the Economic Community of West African States (ECOWAS), Economic Community of Central African States (ECCAS) and the Gulf of Guinea Commission (GGC) with the nudge that led to the articulation and adoption of the Yaoundé Code of Conduct on 25 June 2013, which established a framework for maritime safety and security in the Gulf of Guinea.

Furthermore, some extra-regional actors with interests in the Gulf of Guinea have intervened with initiatives that support security responses to maritime crimes in the region, such as the European Union’s Critical Maritime Route project and the G7++ Group of Friends of the Gulf of Guinea (G7++ FoGG). Other extra-regional measures against illegal maritime activities in the region include the establishment of the Gulf of Guinea Maritime Collaboration Forum and Shared Awareness and De-Confliction (SHADE) in 2021 by Nigeria and the Inter-Regional Coordination Centre. Also, some foreign states such as Belgium, Denmark, France, Italy, Portugal, Russia, Spain, the United Kingdom, and the United States, have acted unilaterally or cooperatively with Gulf of Guinea coastal states to protect their shipping interests in the region.

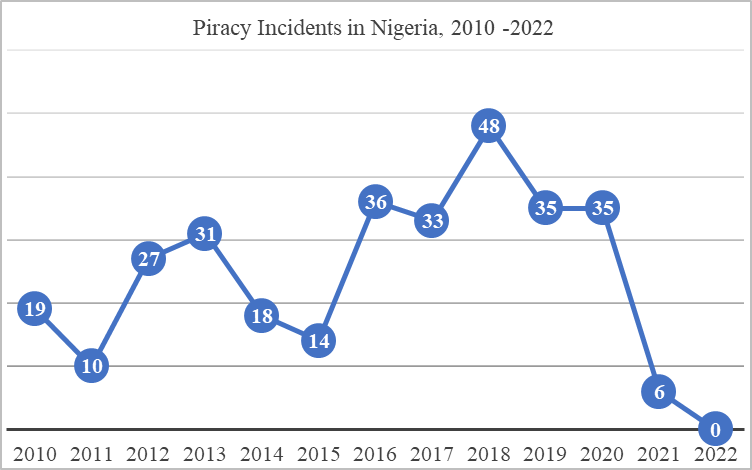

Coastal states such as Nigeria, Ghana and Cote D’Ivoire have strengthened their navies and developed maritime security strategies in response to maritime insecurity. Togo has equally changed its laws and judicial system to allow the arrest and prosecution of ships and persons. Given that almost all pirate attacks in the region originate from Nigeria’s Niger Delta, the Nigerian government enacted the Suppression of Piracy and other Maritime Offences (SPOMO) Act in 2019, to provide a robust legislative framework for the prosecution of maritime crime and piracy. With the SPOMO Act, the government had secured 23 convictions as at August 2022. In June 2021, Nigeria also launched its Deep Blue Project to secure Nigerian waters up to the Gulf of Guinea. As seen in Figure 3, piracy incidents in Nigeria have significantly declined in the past three years.

Figure 3: Piracy Incidents in Nigeria, 2010 -2022

Source: Authors compilation from IMB Report for the years

Overall, national, bilateral, regional and multilateral initiatives are collectively helping to stem the tide of maritime criminality in the region, especially the threat of piracy. Pirate and armed robbery activity continue to decrease in the Gulf of Guinea, as just five incidents were reported in the first quarter of 2023 compared to eight in 2022 and 16 in 2021. The decline in the incident of piracy is a positive development in the region. While concerted efforts by coastal authorities, regional bodies, extra-regional actors and global partners continue to exert positive impact on the incidence of piracy in the region, the threat still remains. The progress made by coastal states under the auspices of the Yaoundé Code of Conduct (Ycc) in information sharing, regional coordination, and strengthening regulations to address the maritime security challenges in the region cannot be gainsaid.

10th Anniversary of Yaoundé Code of Conduct and COPIGoG Project

The 10th anniversary of the Yaoundé Code of Conduct will offer critical maritime stakeholders in the region the opportunity to assess the successes and setbacks that characterise efforts at promoting maritime security in the Gulf of Guinea. To achieve the desired goals of Ycc and UNSCR 2634 (2022), Gulf of Guinea States and the global community needs a deeper and more nuanced approach to understanding and combating piracy. This should be underpinned by research. This is what the authors and group of researchers from global North and South are dedicated to under project ‘Counter-piracy Infrastructures in the Gulf of Guinea’ (COPIGoG). It is pertinent to state that defeating the threat of piracy will be impossible without concerted and conscious efforts at dismantlingthe infrastructures that sustain its existence and episodic ebb and flow in the Gulf of Guinea. Criminal organisations behind piracy in the region exploit physical, social, information and financial infrastructure to execute and sustain their operations. Based on insights emerging from an ongoing study on the operational flow of piracy in the region, building effective counter-piracy response in the region will require in-depth appreciation of not only the root causes of piracy but also the complexity of infrastructure behind its prevalence.

An effective and sustainable solution demands the implementation of robust interventions targeted at dismantling the physical (supply of boats, weapons, and communication equipment), social (interlocking connections between pirate gangs and their supporters, suppliers, financiers, and host communities), financial (networks that enable access to credit facilities, transactions, payment of ransom, and sale of stolen goods), and information (clandestine communication streams and channels) infrastructure, among others, that enable the criminal activity to fester in the Gulf of Guinea. It will require sustained commitment at the national, regional and international levels regarding promoting inclusive coastal community development initiatives to expand opportunities for legitimate livelihood, building community resilience against incentives that nurture criminal activities, detecting suspicious financial transactions related to illicit activities, preventing the smuggling of small arms and light weapons, and strengthening cooperative mechanisms for information sharing. In the long-term, addressing the underlying socioeconomic factors driving piracy is as important as dismantling the infrastructure that sustains it.

This article is part of the project ‘Counter-Piracy Infrastructures in the Gulf of Guinea’ (COPIGoG), funded by a Grant from the Danish Ministry of Foreign Affairs, administered by the Danida Fellowship Centre. The project is led by Katja Lindskov Jacobsen, PhD, University of Copenhagen.