STORY HIGHLIGHTS

- Soldiers deployed in the special force unit do not have barracks, they sleep in classrooms

- Many soldiers in Maimalari barracks construct zinc houses for themselves

- Poor feeding of soldiers across the barracks in Maiduguri and the units in the bushes

- Soldiers on the frontline are owed operational allowance and do not get hazard/danger allowance

______________________________________________________________________________

Gandoki, a corporal with the special force unit of the Nigerian army, walks out of a sport betting shop, scans through the ticket in his hands, then nods as his face widens into a smile. The corporal and many other soldiers fighting Boko Haram insurgents in the north-east do not receive their operation allowance regularly. They find means of survival by gambling, using as low as N50 to predict results of games that could—if by chance their predictions hit it right— enrich them with a few thousands of naira.

“For months now, we’ve not been paid our allowance. How would we have survived if not for the small money that we see from this sport betting?” Gandoki asks, smiling his way to a bar close to where his unit is camped. His predictions on matches in European football league have so far won him almost half the amount of allowance owed him by the Nigerian army.

A few bottles of beer and a plate of pepper-soup are enough consolation for this special force soldier who has just a few days left in Maiduguri, Borno state capital, before returning to the frontline, where the fight continues.

SOLDIERS WEAR SLIPPERS TO WAR FRONT

A standard soldiers’ footwear is dark green camouflage shoes but some who are fighting Boko Haram walk into battle with open-toe slippers. Soldiers in the trenches would reveal that being ‘poorly kitted’ in the army is an understatement.

“Kitting of soldiers? You are on your own,” Gandoki jeers. Then, he yells: “We have our special uniforms that we use as special force soldiers. But nowadays, none of us is still that specially kitted.

“Soldiers now use any type of uniform they can afford. We were even once told that part of the money owed us would be used to buy our uniforms. We were also assured of getting camouflage T-shirts, rather, what we were given were Etisalat branded T-shirts. And when the uniforms came, if you get a trouser, you will not get the shirt. If you get camel bag, you will not get knee guard.

“When they bring the uniforms, they share it among themselves at the top. Even in Abuja, you will see officers that did not train with us being kitted with special force uniforms.

“In NAPEX (Nigerian Army Post Exchange), the store where military uniforms are being sold, each goes for about N25,000. But then, how much is an average soldier’s salary? So, that is why we put on anything we have. And we do that even in the war front. Soldiers who don’t have desert boots and can’t buy canvass, wear slippers.”

Many of the soldiers have not been given fragmental jackets (bullet-resistant vests) since they got drafted into the war theatre. In the bushes where the action takes place, the soldiers don’t expect a luxurious living. They simply want the authorities to provide them with camp beds.

“We buy the beds and tents with our money. Some of us went to Mali in 2013 for an operation where we were fully kitted. When we came back, and redeployed to operation Lafiya Dole, they collected the bed and fragmented jackets from us and were sent to the bush in Bama, at the time the insurgency was very hot. It was hell.”

“We go for parameter patrol without night vision goggles. We go in blindly, and because we are not equipped with these night vision goggles, Boko Haram will be approaching your camp in the night and you will not see them until they are already closer, firing at you.”

‘NOTHING SPECIAL ABOUT SPECIAL FORCES SOLDIERS’

Should soldiers whose unit bears the name special not be given preferential treatment?

Special forces are military units trained to carry out special operations, and in Nigeria, hundreds of soldiers from various divisions and battalions have been specially trained and drafted into this unit where the task is to fight Boko Haram insurgents.

“Anything they call special is supposed to be treated special because of the training you undergo, but there is nothing special in this operation we’ve been in here,” Gandoki says, his chin lowering from disappointment.

“We will be advancing to face the enemies, and all we are given to eat for days is popcorn and biscuits.”

He was a young soldier in one of the divisions in the south-east when a signal was sent to the armed forces; army, air force, navy and the police regarding the assemblage of a select few for special training.

“We were nominated from across battalions, and were assembled at the military cantonment in Jaji,” he said, adding that on arrival, they were told to see themselves as lucky to have been picked for the training. The soldiers saw it a privilege but none of them knew they would end up squaring up against Boko Haram in the north-east.

“The training was in Russia, and we were there for four months. We were supposed to stay up to six months, but there was pressure on us to return and fight.”

‘WE BEGGED OUR ENEMY FOR WATER’

Before departing for Russia, these would-be special force soldiers were given 30% of their training allowance, and assured of getting the remaining 70% upon their return. Sadly, the soldiers’ hopes were dashed as it never came forth.

They never got what they were promised.

Gandoki is in the first batch of the specially trained soldiers deployed to the operation in the north-east, and their first assignment, upon return in 2014, was to engage Boko Haram insurgents in Sambisa forest.

“We were about 200, advancing into Sambisa, and the first problem started when we weren’t given food or money to feed,” he says as his voice dropped again.

“On this first assignment to the bush, some died and, luckily, some of us returned alive. If you see the kind of food they would eventually give us, you will weep for us. There was a time we were begging our enemy for water, because we were going to die of thirst. The military helicopter, we were told, would bring water but wouldn’t be able to land because where we are is not safe for it. And, I would ask, what about us on the ground here?”

The insurgents may have killed quite a number of soldiers, but these fighters say lack of food and water should also be held responsible for soldiers’ death.

LIVING WITH PAIN

Gandoki, who has been in the operation for three years, has sustained injuries and not much has been done in taking care of him.

“I have two gunshot wounds on my body,” he says, reaching for his leg and back where the injuries are. “There is rubber inside my leg because the vein almost cut off so they have to brace it with rubber. And, nothing has been given to me to sort my medical bills, even when we heard that money was released to take care of some of us who have been affected.”

He is a victim of Damasak and Gashiga attacks in Borno. The task was to clear a Boko Haram hideout, and the special force battalion was to meet with a strike group in Abadam, still in Borno, where they were to proceed to collectively strike the hideout.

“We took off and on our way we had an issue with our vehicle, and we spent the whole day trying to fix it. In Gashiga, we entered Boko Haram ambush. We called our jet, and there was no response. We started a battle with the enemies and it was there I got hit with multiple bullets.”

Gandoki’s vehicle had run into the mines and while the soldiers were trying to pull themselves out, the insurgents started shooting at them. “With our injuries, we withdrew to Damasak, and after a while, we advanced again and this time, the attacks were overwhelming.”

The insurgents outnumbered and then overpowered the “battalion”. “We call it a battalion but what we have is actually a company, yet those generals at the top get monetary allocations for a bigger battalion while the formation sent to fight in the bush is the smaller company.”

More than 40 soldiers were killed. The soldiers were not the size of a battalion that they should be, and then, the machines they were left to fight with were faulty.

“The two scorpions we had were not working,” Gandoki explains. “The general purpose machine gun (GPMG) mounted on the scorpions were faulty, too. I don’t know why they are not serviceable, and instead of the commanding officer to tell the theatre commander, he was pushing us to the frontline and there we got ambushed.

“They said it is a battalion, but let me tell you the truth, it is not a battalion that is deployed to Gashiga. It is a company. A company has about 200 soldiers as against a battalion of 800 soldiers. Those in authorities label us a battalion so they can get the money meant for about 600 soldiers.”

The soldiers had managed to fire one bomb before the machines stopped working. Advance, attack, withdraw and defense are the four phases of war, and since their machines were not forthcoming, they had to withdraw, but sadly, they couldn’t defend.

While some injured special force soldiers couldn’t get out alive, Gandoki had found himself in the hospital.

The morning after they were “dumped” at the hospital, Gandoki said the pain was becoming unbearable for him, and he started crying, calling for help. An officer who was moved by Gandoki’s plight came to him, helped him get on a wheelchair and he was wheeled to where his bullet-ridden leg got scanned. Even when the scan had showed bullets inside his leg, it took three days before he was moved into the theatre for surgery. He said throughout his stay alongside other soldiers at the 7 Division hospital, the army left them with no food.

Since the surgery, Gandoki says he has not had any post-surgery treatment. Apart from his leg injury, sounds of gunshots and IED explosions had affected his eardrums— such that until a word or phrase is repeatedly said, he can barely understand.

His left ear functions no more.

“From the army hospital, I was referred to the University of Maidugri Teaching Hospital,” he explains. “But, it is better you sit at home and find a way of treating yourself than go to any of these hospitals. You will spend money transporting yourself to and fro the hospital and you get there, sit for hours because nobody would attend to wounded soldiers. They will keep telling you doctor is coming. We will be there, tired, in pains and waiting on empty stomachs.”

If a soldier is wounded and goes for treatment and has not returned within three to five days, Gandoki says such soldier’s account would be frozen.

“They will say he has gone AWOL. If you sustain a bullet wound while fighting in the bush, you are supposed to RTU (return to unit). But now, they will ask you to return to front line.”

When Gandoki refused to return to the front line, he was slammed with a two-count charge; disobedience and failure to perform military duty.

Gandoki has lost hope in the hospitals. He had thought as a special force soldier, he would have enjoyed some special medical treatments. The strong-willed fighter now uses salt and water to mop his injured leg, a post-surgery treatment he can afford. And for his bad ear, he uses cotton wool to cover it.

SOLDIERS SLEEP INSIDE CLASSROOMS

Special force soldiers deployed for operation Lafiya Dole have been camped in classrooms of a secondary school along Gubio road, outskirt of Maiduguri.

“When we return from the bush, these are the classrooms we live in,” Gandoki says, shaking his head. “One has spent six months in the bush, and when you return to Maiduguri to shop for a few things— after being on the road for about 12 hours— you come to sleep on the floor of this classroom, because you have nowhere to sleep. Even when the commanding officer came and saw our condition, he shook his head, pitying us.”

He adds that soldiers who have mattresses got them from deserted villages.

“I sleep inside the tank,” Gandoki’s friend who does not have a space in the classroom says. “We get mosquito net ourselves for N400, because if you wait for the army, mosquitoes will kill you here.”

‘IF I DO NOT WET THIS FLOOR, THE DUST MAY KILL ME OVERNIGHT’

Rusty zinc houses where hundreds of soldiers rest their heads are scattered on the dusty expanse of land inside the Maimalari barracks in Maiduguri.

One evening, Danje, one of the old serving soldiers in operation Lafiya Dole, returns from Konduga, tired but he still had to fetch water some metres away so he can wet the sandy floor of his zinc house.

“If I do not wet this floor, the dust may kill me overnight,” Danje says, flashing a smile as he drops his rifle and picks up a bucket. For three months, he has not been paid, too, but as soon as he gets his operational allowance, he intends to buy five bags of cement and fill the room with concrete.

“When we arrived here many years ago, with all our loads, we were told all the blocks of flats in the barracks have been occupied,” he explains. “And you know, as soldiers, we just have to find our way.” For almost a year, Danje says, he will spread his mat atop one of the abandoned and faulty vehicles at a mechanic workshop to spend the night. He did this until he was able to save enough money, like other soldiers, to construct his own zinc house.

“This is my own self-contain apartment,” he laughs. “I built this place myself, with my money and my hands. A sheet of fairly used zinc sells for N700, while the new goes for N1,000, we can only afford the former. And to put this whole structure together, you will spend at least N31,000 on zinc alone.”

Danje says soldiers have been abandoned and that the authorities do not make an attempt to refund them. “Soldiers would go to the bush to fight, and when some of us are lucky enough to return here, are we supposed to be spending our own money to construct where we will rest our heads? Is it not the responsibility of the Nigerian army to make provisions for our accommodation here?”

The soldier says his condition is better than some of his colleagues who still have nowhere to put their heads. “The system here is; carry your cross, I carry my cross.”

FOOD WITHOUT MEAT

Willie has just been posted to Maiduguri. The young soldier is three weeks old at Giwa Barracks and he is struggling to come to terms with being served food without meat.

“Not once, in my three weeks here have I tasted meat,” Willie says, as he waves off the teeming flies on the wrap of semovita and watery soup by his side.

“All they give us here; beans, rice and semo, we have never eaten vegetables here. They will share food by 5:00 pm and if you do not rush, you will not get food.

“By right, our feeding timetable says every Saturday, I will eat food with soft drinks or bottle water or sachet water. We are also supposed to get fruits twice in a week, but we don’t get all of those. They said they will give one soldier one bag of water for a week but we don’t get it. Before, from theatre command, we heard they used to give soldiers popcorn and juice but not anymore, and we don’t know why.”

Once, the soldiers were to advance to the bush for a task and they “had to buy garri and take along, because we were not given food, and we were going to walk some 15 kilometres”.

The experience is the same with soldiers in Maimalari Barracks and those currently in the bush.

“Yesterday, they gave us one soup you cannot even describe as okra or ewedu,” Jacko, a soldier in Maimalari turns their feeding into a subject of mockery. “The food was tasteless, and this morning, they cooked beans and pap; the pap, oh my God, o my God!”

‘WE STARTED EATING HUMAN FLESH WHEN FOOD SUPPLY STOPPED’

His eyes are almost covered with blood clot, with his eyeballs uncomfortably positioned. He looks strange — like a character in a horror movie.

Gimzy, a sergeant, has spent the last three years, from one bush to the other in the dreaded Sambisa forest, and now he is back in Jimtilo Barracks, Maiduguri.

“I lived in Sambisa for three years,” he begins, adjusting the rifle dangling around his arm, and groping for a stick of cigarette from his chest pocket. Like many others, Gimzy and Motu, his brave wife who lived with him in Sambisa, have not had an accommodation in the barracks since they returned. “And, I don’t have any money, my wife and I just found one corridor to sleep when it’s dark. But, they keep telling the whole world we soldiers are fine that they are taking care of us, that they are paying us.”

Gimzy is more worried about food than accommodation. While in the bush, they were being supplied food, but at a point the food stopped coming and soldiers were left to fend for themselves.

“Normally, they bring in food for us with gun trucks and escort. And it takes days before they get to us, that is if they are not ambushed by the enemies. But for almost three months we didn’t get food and we had finished all we have, we gathered that the enemy had set ambush everywhere and it was hard to get food across to us.

“And they don’t use helicopter to supply us food, because the hovering helicopter would reveal our location to the enemies.”

MANY SOLDIERS HAVE EITHER SALARY OR ALLOWANCE PROBLEM

https://w.soundcloud.com/player/?url=https%3A//api.soundcloud.com/tracks/495159987&color=%23ff5500&auto_play=false&hide_related=false&show_comments=true&show_user=true&show_reposts=false&show_teaser=true&visual=true

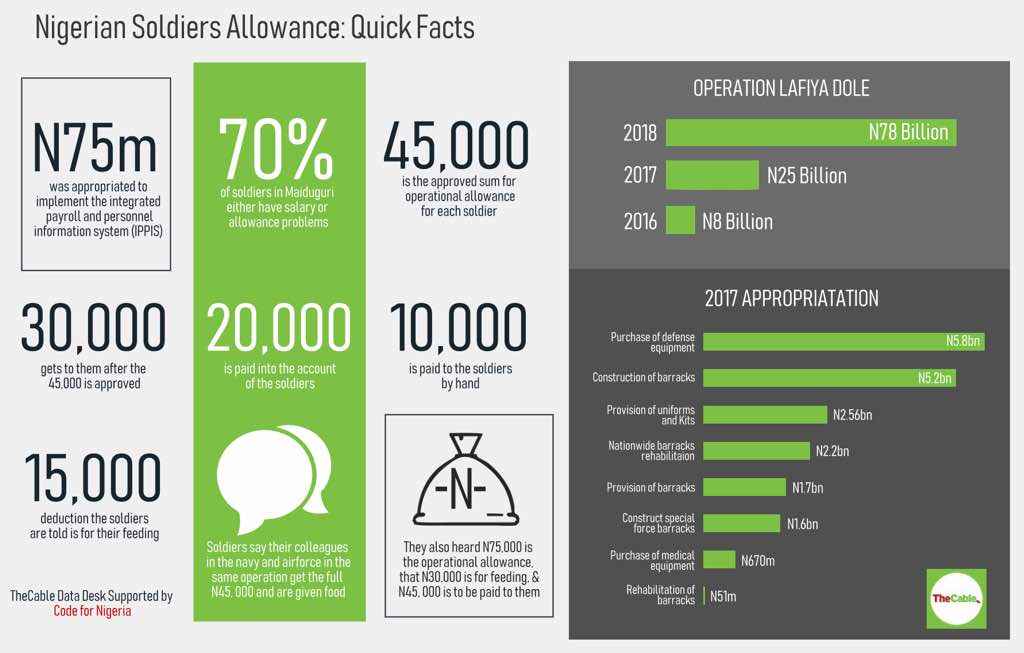

The administration of former President Goodluck Jonathan had re-initiated the integrated payroll and personnel information system (IPPIS) where payment of salaries and wages were to be directly paid into the government employees’ accounts. The main aim of the system is to pay accurately and on time with the statutory and contractual regulations.

About N75 million was appropriated to implement this. In September 2017, the presidential initiative on continuous audit (PICA) wrote to the armed forces to submit its payroll for migration to IPPIS, but soldiers at the frontline accused the army authorities of not responding as irregularities continue to dog their payment.

“We heard the navy and air force have submitted the payrolls of their personnel for IPPIS, but it does not appear the army has,” says Kazau, a soldier who is yet to get his two months pay.

“Our money comes through the army authorities, and before it gets to us, they would have cut from it. And that is why we have been praying they agree with the IPPIS so that we can get paid directly from the government.

“Seventy percent of soldiers in Maiduguri here either have salary or allowance problems. Some soldiers are owed nine months allowance, and you will still be sent to the bush despite the suffering because you don’t have an option.”

NO DANGER ALLOWANCE, SHORTCHANGED ON OPERATIONAL ALLOWANCE

For each soldier fighting insurgency, N45,00, they understand, is the approved sum for operational allowance. But, of this approved sum, N30,000 is what eventually gets to them. N20,000 is paid into their account, and N10,000, a hand-to-hand payment. A deduction of N15,000, the soldiers are told, is used for their feeding.

The soldiers feel cheated. They say their counterparts in the navy and air force who are also in the operation get the full N45, 000, and they are given food.

“In fact, we heard the operational allowance is originally N75,000 from which N30,000 is for feeding, and the remaining N45, 000 is to be paid to us,” a soldier in Baga explains.

“Apart from that, if a soldier is going on pass, he is supposed to be given transport allowance or a military vehicle drops him, but we don’t get that here.”

Soldiers who have been in the operation for over three years and are daily exposed to danger on the frontline have not, for once, been paid danger allowance, and this, the soldiers say they are entitled to.

BUT, WHAT HAS HAPPENED TO THE BILLIONS APPROPRIATED BY THE ARMY?

“We will devote a significant portion of our recurrent expenditure to institutions that provide critical government services. We will spend N369.6 billion in education; N294.5 billion in defence; N221.7 billion in health and N145.3 billion in the ministry of interior. This will ensure our teachers, armed forces personnel, doctors, nurses, policemen, fire fighters, prison service officers and many more critical service providers are paid competitively and on time,” President Muhammadu Buhari said in 2016 when he presented his ‘budget of change’ to a joint session of the national assembly.

Eight billion naira, N25 billion and N78 billion were appropriated for operation Lafiya Dole in 2016, 2017 and 2018 respectively.

In the 2017 appropriation, the ministry of defence budgeted N2.2 billion to rehabilitate barracks nationwide. There is also a separate budget of N1.7 billion for the construction/provision of barracks while another N1.6 billion is budgeted to construct special force barracks.

In the same budget, the Nigerian army is to purchase defense equipment for N5.8 billion, construct barracks for N5.2 billion while N51 million on is for rehabilitation of barracks.

N2.56 billion is budgeted for the provision of uniforms and other kitting items, and N670 million for the purchase of health/medical equipment.

N5.5 billion is for the provision of barracks and N1.4 billion for uniforms and kitting in the 2016 budget.

In spite of these huge budgeted sums, the soldiers at the end of the chain feel no effect.

ARMY AUTHORITIES NOT SAYING ANYTHING

Twice, the army refused to respond to a FoI request sent for budgetary and fund release records.

Same request was also sent to the office of the accountant-general of the federation, and there has been no response.

When contacted, the Nigerian Army Finance Corps asked TheCable to return to the army headquarters in Abuja. An officer at the corps office in Lagos who pleaded to be anonymous, however, said the top generals are to answer for these funds.

“Indeed, funds were released for our troops but they boys in the bush are being shortchanged,” he says. “Check out those generals, and ask them where they get money to build mansions and estate in Abuja and soldiers don’t have where to sleep when they come out of the bush.”

The information requested from the army were; a breakdown of amount released for the construction/rehabilitation of barracks across Borno, Yobe and Adamawa states; the name of each construction/rehabilitation project for which funds were approved from January, 2014 to October, 2017; a breakdown of total amount released to kit soldiers and officers in Borno, Yobe and Adamawa states from January, 2014 to October, 2017; a breakdown of total amount released as operational/danger allowance for soldiers and officers drafted into the Operation Lafiya Dole across Borno, Yobe and Adamawa states.

Interestingly, in the 2017 appropriation, the ministry of defence earmarked N20 million for a line item it called “implementation of FoI”.

Jude Chukwu, army spokesman wouldn’t hide his anger when he was reached for comment over the poor welfare of troops fighting insurgency.

“Which soldiers? I am with the soldiers you are talking about and I don’t know who is giving you that report,” he said with an unfriendly tone.

“Sometimes you people will just be asking some questions that one would just imagine how you people came about it. Do you know the meaning of a soldier? If you know the meaning of a soldier, you wouldn’t ask that question. You wouldn’t ask me whether a soldier can comfortably be taken care of or not. People are fighting war, and you are talking like this? Do people stay in the room and be fighting war?”

Chukwu, beating his chest, said no soldier ever complained of poor welfare.

“You journalists just pick up something. Soldier have enough, they have food to eat. No issue with welfare, I don’t know why you are asking.”

Chukwu, however, did not respond to why the army authorities failed to make available information on how funds have been spent on the soldiers’ welfare.

*Names and designation of soldiers have been altered to protect their identity.

This investigation by The CableNg is supported by the John D. and Catherine T. MacArthur Foundation and the International Centre for Investigative Reporting, ICIR