French President Emmanuel Macron met with Russian President Vladimir Putin this week in an attempt to ease the standoff with Russia over the fate of Ukraine. As Celia Belin writes, “such long-odds shuttle diplomacy has been characteristic of Macron, who has made high-profile, if often exceedingly ambitious, diplomatic interventions a hallmark of his five years in office.”

Monsieur Fixit :The Perils of Macron’s Shuttle Diplomacy (By Celia Belin)

It was Charles de Gaulle, president of France from 1959 to 1969, who perhaps best encapsulates the post–World War II French leader wanting to commandeer the international stage. In de Gaulle’s mind, France could “never recognize a hegemony other than her own,” Herbert Lüthy wrote in 1965. Some of the frustrations U.S. policymakers had with de Gaulle stemmed from his less pragmatic and more theoretical approach to world affairs, Henry Kissinger argued in 1963. “The unsatisfactory nature of much of our dialogue with Germany and France derives from the fact that their current leaders are a very different sort … Their reality is their concept of the future or of the structure of the world they wish to bring about.”

U.S.-French clashes culminated in 1966 when de Gaulle decided to kick NATO forces out of France. France’s ambivalence toward the United States persisted throughout the Cold War, as David Yost observed in a 1990 essay: “The French want a U.S. military and nuclear presence in Europe, but not on their soil.” But the uncertainty that accompanied the demise of the Soviet Union, Yost noted, had French leaders rethinking the country’s military posture and its role in the Atlantic alliance. The “factors supporting France’s privileged and unique security position may disappear.”

Dominique Moïsi noted in 1998 that “the French always seem to be opposing the United States on some issue or other.” Part of this was due, he wrote, to the French discomfort with being a middle-range power: “The less confident France is, the more difficult it is to deal with.”

The Trouble with France (Dominique Moïsi)

When U.S. President Donald Trump took office, Macron saw an opening, Natalie Nougayrède observed in 2017: “[W]ith the United States’ image, global role, and reliability newly uncertain, Europeans feel a void that someone must fill—and France thinks it should at least try to do just that.” Macron also attempted to curry favor with Trump, due in part to terrorist attacks in France that made cooperation with Washington more imperative. “France can ill afford to dispense with U.S. help in the fight against the Islamic State (or ISIS) and other terrorist groups, whether in the Middle East or the Sahel,” Nougayrède wrote.

France’s Gamble: As America Retreats, Macron Steps Up (By Natalie Nougayrède)

Macron’s vision today is one of “strategic autonomy,” which he interprets as “a Europe with its own place in the world and its own ability to shape world events,” Francis Gavin and Alina Polyakova pointed out last month. But the French president’s approach could backfire. Macron’s vision, they warn, “could splinter Europe and dilute its capabilities and focus, all while playing into the United States’ worst instincts to disengage from the transatlantic alliance.”

Macron’s Flawed Vision for Europe: Persistent Divisions Will Preclude His Dreams of Global Power (By Francis J. Gavin and Alina Polyakova)

**********

The Perils of Macron’s Shuttle Diplomacy

By Celia Belin (10.02.2022)

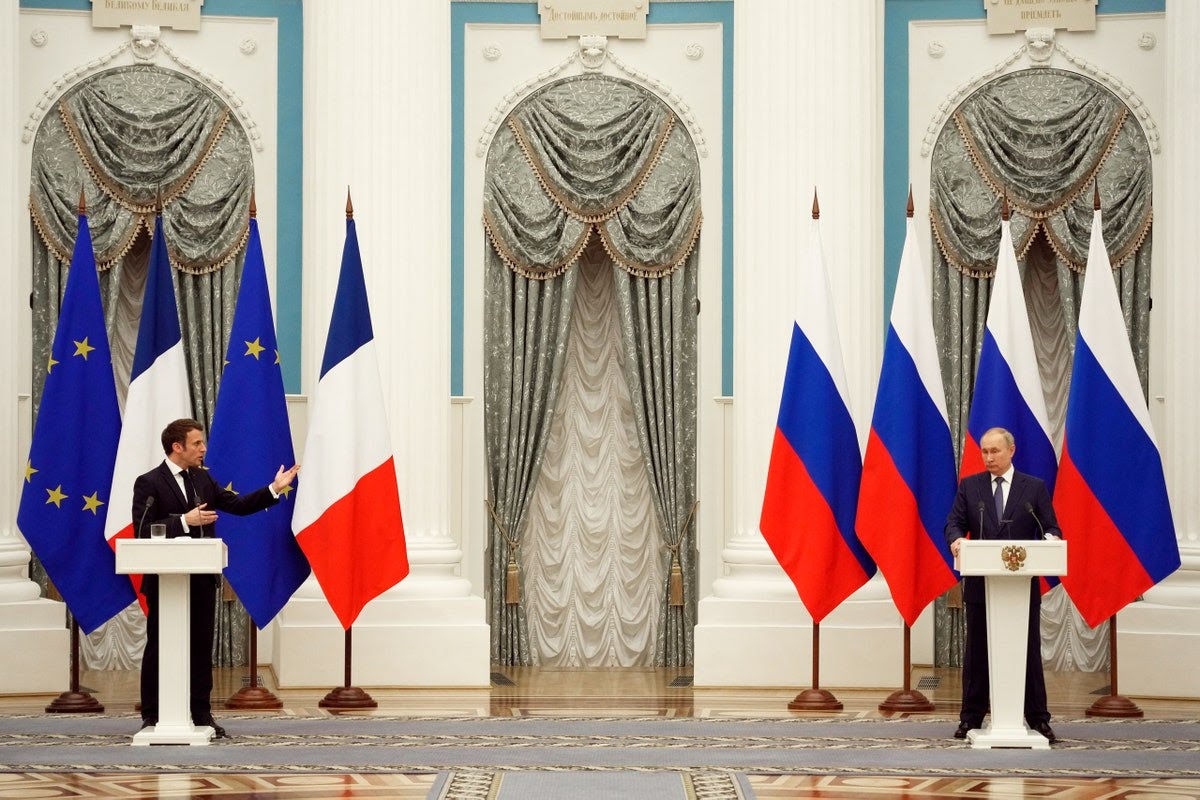

Just two months before he stands for reelection, French President Emmanuel Macron has launched a bold effort to mediate between Russian President Vladimir Putin and the West over the standoff at the border with Ukraine. After meeting with Putin for five hours on February 7, Macron struck a hopeful tone, telling reporters that Putin had assured him that there would be “no degradation or escalation” of the crisis by Russia. But the following day, as Macron met with Ukrainian President Volodymyr Zelensky in Kyiv before flying to Berlin to meet with his German and Polish counterparts, the Kremlin denied that Putin had made any specific commitment to Macron. From the start, it had been unlikely that these meetings would have much effect: Russia and Ukraine remain very far apart on the status of the Donbas and Ukraine’s sovereign right to decide its own future, and Russia has made de-escalation contingent on demands regarding NATO that many in the West view as unacceptable. Yet this bleak outlook didn’t discourage the French president: such long-odds shuttle diplomacy has been characteristic of Macron, who has made high-profile, if often exceedingly ambitious, diplomatic interventions a hallmark of his five years in office.

On issues ranging from reforming European governance to dealing with crises in the Middle East, Africa, and now Ukraine, Macron has pursued a fast-paced, extremely active foreign policy. During the Trump administration, he was one of the few Western leaders to make a point of cultivating a relationship with the American president, despite vast policy differences. And Macron has consistently pushed to shore up the European Union’s sovereignty, independence, and power in an increasingly competitive world.

Yet the results of these efforts have been mixed. Macron’s personal attempts to resolve crises such as the U.S. withdrawal from the Iran nuclear deal and the diplomatic dispute between Lebanon and Saudi Arabia have not generated durable outcomes. Rapidly deteriorating relations with the ruling military junta in Mali as well as widespread political instability in the Sahel and West Africa are forcing France to reconsider its long-running counterterrorism mission in the region. Nor have Macron’s efforts to start a strategic dialogue with Russia, which he began in 2019 without broader European support, produced tangible results. They did succeed, however, in fueling suspicion among European partners that Macron was not committed to following a unified European strategy, rendering France’s current mediation efforts in Ukraine all the more difficult.

Indeed, Macron’s foreign policy often leaves observers puzzled. At times, he appears to be a ruthless dealmaker, brushing aside the norms and protocols of diplomacy with the faith that his political talent alone can solve entrenched conflicts; at other times, he seems to be a devoted multilateralist, bringing together leaders around Paris-led initiatives such as the One Planet Summits, which seek to promote cooperation on climate change, and the Paris Peace Forum, a newly created conference on global governance. Although he has long made clear his determination to turn the European Union into a great power, Macron often seems to favor bilateral or ad hoc formats or going it alone. And although Macron’s supporters applaud his audacity and agility, his critics accuse him of grandstanding and opportunism. The Ukraine crisis is no exception. At a time when many of France’s European allies are laser focused on maintaining unity, Macron has insisted on the importance of a revised European approach to Russia even at the risk of undermining U.S.-led negotiations with Moscow.

Now, as Macron comes up for reelection, new questions remain about what his underlying foreign policy goals are and how, with a renewed mandate, he might pursue them. At the core of his efforts is a drive to position France at the center of Europe and Europe as a stabilizing alternative to a bipolar world dominated by the United States and China—all the while ensuring that France’s own interests are heard loud and clear. As Europe faces its most serious security challenge from Russia in decades, and with France now holding the presidency of the Council of the European Union, Macron has a golden opportunity to prove the merits of his particular brand of pragmatic and personalized foreign policy to Europe and the world. But his strategy has also raised the stakes—for his reelection, for France’s voice on the global stage, and for the future of Europe.

TOGETHER AND ALONE

At the time of his 2017 victory over far-right candidate Marine Le Pen, less than a year after the Brexit referendum and the election of U.S. President Donald Trump, Macron was embraced by many as a bulwark against a rising tide of nationalist populism. The young French president seized on this image and quickly worked to establish himself as the liberal leader of a multilateralist camp. As the Trump administration distanced itself from the international order, Macron worked to fill the vacuum of global leadership—by championing the Paris agreement on climate change after Washington’s withdrawal, defending the Iran nuclear deal, and rallying partners and allies behind international efforts ranging from ensuring global access to COVID-19 vaccines to preventing radicalization and violent extremism online.

But the image of Macron as a “multilateralist in chief” fails to account for some of the unusual bilateral relationships he has cultivated—including with Trump and Putin—often to the distaste of other European leaders. In many ways, Macron’s self-identification as a “progressive” has less to do with a political philosophy than with a method. In a 2019 pamphlet, Le progrès ne tombe pas du ciel, David Amiel and Ismaël Emelien, two former Macron advisers, defined his progressivism as “maximizing possibilities,” with the mission of “expand[ing] individual opportunities and perspective.” In practice, this has translated into an unorthodox, risk-taking foreign policy. Consider Macron’s convening of rival Libyan factions in a surprise effort to relaunch a political process in Libya or his rushing to Beirut after the deadly port explosion in the summer of 2020 and berating the Lebanese political class for their shortcomings. To Macron’s critics, these efforts have amounted to little more than public relations stunts. But the French president seems to believe that if there are enough wins, the losses won’t matter: possibilities will have been maximized and opportunities will have been expanded.

A FRENCH UNION

Macron’s foreign policy does have one identifiable end goal: bolstering and transforming Europe. Although his predecessors blamed Brussels for France’s own failures, Macron embraces the European Union unapologetically. As he sees it, by making Europe stronger, France can maximize its influence: as he wrote in his 2016 book Révolution, Europe must be approached as a “true political project,” because “Europe is our chance to recover our full sovereignty.” For Macron, France alone cannot confront the global challenges of migration, terrorism, climate change, and digital transformation or withstand the power of the U.S. and Chinese economies—but a sovereign Europe can.

Focusing on Europe has largely served Macron well, and France’s influence in Europe has only grown in the past five years. Macron has reaped successes on a range of fronts: he has worked to overhaul rules governing mobile workers within the European Union; he has supported the establishment of an EU defense fund to foster Europe’s military industrial base; and he has helped design a new European Commission in a direction favorable to French interests. With former German Chancellor Angela Merkel having departed from the political scene and the new German leadership still finding its footing, Macron has also been given greater stature to lead Europe.

Macron believes that the pace of change in the world compels him to tackle every problem, on every front, at the same time.

And France currently presides at the Council of the European Union, for which Macron has no shortage of ambitions, such as advancing European legislation on digital affairs, pushing for an EU-wide minimum wage and a carbon border tax, encouraging a reform of migration and asylum laws, holding a summit with the African Union, and adopting the Strategic Compass, a security proposal which lays out a common vision for European defense. The range of the French proposals reveals the enormity of the work that is commonly carried out by EU institutions, but it also reflects an unfortunate lack of prioritization on Macron’s part. For the political analysts Francis Gavin and Alina Polyakova, despite Macron’s calls for Europe to assert its “strategic autonomy,” his actual proposals appear to be more of a “laundry list” of disparate ideas that “dilute its capabilities and focus.”

Other European leaders have not always played along. Macron’s “centrist revolution” has been stymied by nationalist forces on one side and the forces of the status quo on the other. As the Europe experts Yves Bertoncini and Thierry Chopin have argued, leadership in Europe requires humility, patience, and a capacity to create consensus—characteristics that stand in sharp contrast to Macron’s “imperial” approach, his occasional failure to consult European allies, and his often grandiose rhetoric. At times, Macron’s willingness to carve his own geopolitical path has generated backlash among his European peers: his unilateral launch of the strategic dialogue initiative with Russia in 2019, combined with his infamous description of NATO’s “brain death” in The Economist a few months later, made him appear out of sync with the rest of the continent rather than at its helm. Nonetheless, the current crisis with Ukraine has only reinforced Macron’s conviction that a strategic dialogue with Russia is needed. Although Washington seems convinced that a Russian invasion is imminent, Macron insists that war can and must still be avoided. With that objective in mind, he is pushing for the implementation of the 2014 Minsk Agreement that sought to end conflict in the Donbas, but he also seems open to discussing fundamental questions behind Europe’s security architecture in relation to Russia such as risk reduction efforts, arms control treaties, and transparency measures.

Macron’s approach, however, can be viable only if other European leaders are on board. Notably, in contrast to the United States and other Western powers, Macron has suggested that Russia is “legitimate” in stating that its security needs should be discussed. As Europe is threatened by Russia’s troop buildup on the Ukrainian border, it behooves France, as the holder of the Council’s presidency, to play the role of honest broker in the determination of a collective stance. Macron must first and foremost work to reassure Europeans on France’s position.

DISRUPTIVE REALISM

Observers have struggled to describe Macron’s foreign policy doctrine, which Macron himself has declined to define. To the former French diplomat Michel Duclos, Macron is an “eclectic spirit” whose foreign policy consists of a “disruptive realism,” seeking to “face problems head on, assume conflict with interlocutors, use difficulties and disagreements to gain leverage.” As the Le Figaro diplomatic correspondent Isabelle Lasserre has written, Macron doesn’t mind letting a chaos of ideas reign in the Élysée Palace, although “in the end, Emmanuel Macron decides on his own.” Macron’s relations with the French Ministry of Foreign Affairs over foreign policy have long been fraught, in particular concerning his insistence on a dialogue with Russia, which has encountered quiet resistance within the French diplomatic corps. Unfazed, the president continues to concentrate decision-making at the top and imposes a frenetic rhythm of work.

If Macron is impatient, it is not just a function of his youth or character—it is a function of his worldview. The French president believes that the pace of change in the world compels him to tackle every problem, on every front, all at the same time. Democracies, in his view, cannot afford to be slow and ineffective at a moment when the lives of their citizens are being upended, whether as a result of rising inequality, digital transformations, climate change, or pandemics. He has often called for a “results-driven multilateralism” aimed at leading and promoting desired policy goals rather than waiting for them to be imposed by others.

Macron has paid a growing price for his impatient pragmatism.

Macron’s frenzy to meet the moment affects Europe, too. Europe, Macron believes, must have a strong voice at a time of large-scale social and political change—and he is willing to take on the mantle of leadership even at the occasional expense of relationships with his neighbors. In particular, he argues, Europe needs to be less economically and strategically reliant on the United States and China. The European Union can do so, he asserts, by giving itself greater sovereignty and regaining control over its markets, its borders, and its security. If it fails to do so, predatory powers such as China and Russia will increasingly limit Europe’s influence and independence, as they have already begun to do. And Europe’s security is deteriorating faster than Macron’s capacity to rally European partners around concrete common defense projects.

The United States remains a particular challenge for Macron. Ever since the Biden administration came to power, Macron has had difficulty calibrating France’s positioning relative to Washington’s. Despite his self-characterization as a progressive fending off nationalists, the French president has done nothing to embrace the Biden administration’s democracy agenda. His camp is also indifferent, if not outwardly hostile, to the particular brand of progressive American thinking that underpins the Biden coalition.

The gap between France and the United States is widening on security challenges, too. The dispute with Washington over the AUKUS submarine deal—which preempted France’s own submarine deal with Australia—although well managed in the aftermath, exposed a structural vulnerability: as the United States increasingly focuses on Asia, its relationship with France, which in the years after 9/11 had become a crucial partner in the fight against terrorism—has lost some of its urgency. The current Ukraine crisis seems likely to test the U.S.-French relationship even further. For now, the United States has cautiously supported Macron’s effort at diplomacy—but skepticism runs high, as Washington believes that Putin is determined to invade either way. Macron seems to recognize the necessity of presenting a somewhat unified front with the United States. On February 8, he and his Polish and German counterparts echoed Washington by warning Moscow of far-reaching political, economic, and geostrategic consequences should Russia breach Ukraine’s territorial integrity. As Macron positions himself as the world leader capable of steering Putin toward a path of de-escalation—and of recalibrating Europe’s security architecture with less reliance on Washington’s help or input—he must tread lightly in order not to appear to be opening a rift among allies at a time when unity is the best deterrence against Russia.

MORE CHANCES, MORE RISKS

As his first term comes to an end, no one can deny that Macron has transformed the way France asserts its leadership in Europe and internationally. Arriving in office declaring that he is beholden to no particular ideology, he has not let historic allegiances, customs, or his own inexperience get in the way of his ambitions. With time, however, Macron has paid a growing price for his impatient pragmatism. In the current crisis with Russia, France’s role as an honest broker has been weakened by suspicions from allies that Macron may be blind to the true nature of the Putin regime or intrinsically opposed to U.S.-led negotiations.

Should Macron be reelected for a second term, he will be given a further chance to turn his frenetic foreign policy into concrete results. Macron’s success in the coming months will be inextricably linked to that of the European Union: if he is able to get the EU to adopt an ambitious common defense strategy and push through new new digital or carbon rules, he will be able to claim a productive presidency. But he will also have to take care of a rapidly deteriorating situation in Mali and political instability throughout West Africa and decide whether to pull out troops, with the acknowledgement of failure that such a move might convey. Hardest of all will be to maintain a united, collective European voice on the question of Russia and Ukraine, especially if the situation deteriorates rapidly. Macron’s course correction from his unpopular, unilateral, and unfruitful strategic dialogic with Moscow in 2019 to the care he has now taken to consult with allies on Russia sets him on a good path to help guide Europe through a turbulent future. But the French president’s impatience, audacity, and consistent impulse to maximize possibilities may continue to cost him—and the continent.

CELIA BELIN is Visiting Fellow at the Center on the United States and Europe at the Brookings Institution.

************

The Trouble with France

By Dominique Moïsi (05/06/1998)

A ROTTEN MOOD

To Americans, France is a beautiful country, home to that most elegant of cities, Paris, the seductive tones of the French language, and some of the world’s finest wines, which makes it all the more difficult for them to understand how such a charming nation could be so irritating an ally. The French always seem to be opposing the United States on some issue or other, whether it is in the realm of international diplomacy, where between the lines of France’s carefully worded diplomatic statements one can discern a distinct distaste for America’s oft-proclaimed sole-superpower status, or on matters of culture, where France is always the first to denounce American “cultural imperialism.” Lately, Franco-American friction has manifested itself most visibly in the Persian Gulf, where France’s interests—in Iraq and Iran—seem to clash with America’s security needs. Many Americans ascribe France’s prickliness to the legacy of “Gaullism,” the conservative, nationalist inheritance bequeathed by that country’s greatest twentieth-century leader. But in France nobody even knows what Gaullism means anymore, apart from being able to say no to the United States.

In fact, the annoying behavior coming out of Paris is best explained by the fact that the country is, quite simply, in a bad mood, unsure of its place and status in a new world. The less confident France is, the more difficult it is to deal with. On the eve of the 21st century, France faces four major challenges, which are together the source of its melancholy. The first is globalization, which is often blamed for the erosion of France’s culture and its depressingly high levels of unemployment. (Last year, one of Paris’ biggest bestsellers was a tract titled The Economic Horror—a bitter philippic against globalization’s ills.) The second is the unipolar nature of the international system, in which the United States leads and a once-proud France is grudgingly forced to follow. The third is the merger of Europe, which threatens to drown out France’s voice. The fourth, and by far the toughest, challenge is France itself. The nation must overcome its economic, social, political, moral, and cultural shortcomings if it is to successfully face its other challenges. The rise of Jean-Marie LePen’s extreme right National Front is symptomatic of France’s internal difficulties. To combat them, France must, in essence, transcend itself.

IT’S NOT EASY BEING MEDIUM

All men are equal, but some are more equal than others. In the age of globalization, size matters. If small is beautiful and big is powerful, then medium is problematic. The Internet, information technology, and other trappings of the global economy can reinforce the centrality of the United States or multiply the strength of a small city-state like Singapore, but they often penalize middle-size countries like France. France’s special strengths are its culture and its heritage, and these are being worn away, replaced by a “universal culture” that looks strangely American. If France were a young state, less set in its ways, less burdened by the weight of old traditions or images from the past, it might be able to adapt. But France is an ancient country. It cannot forget its history, and in trying to reconcile it with elements of the modern world ends up merely superimposing it upon them, creating a hodgepodge that is true to neither. Tellingly, France’s most popular computer game today is not a high-tech, outer space adventure, but a thriller called “Versailles,” which takes place amid the grandeur of the court of Louis XIV.

Consider the difference between France and the United States. America is not only big and young; it is, above all, open. French society remains closed and rigid—incapable of attracting the best talent from other countries while unwittingly supplying its own to America. For example, Dr. Luc Montagnier, co-discoverer of the AIDS virus, now teaches and conducts research in the United States because he reached mandatory retirement age at the Institut Pasteur. Contrast the essential message of Hollywood—if you want to make a difference you can—with the classical archetype of the French movie: A loves B, who loves C, who loves D, all of whom end up in despair. America’s flexibility can be seen in the success of its melting pot, which, in an age of globalization, is exported worldwide. Today, the sounds of the world are essentially African-American, everybody eats Italian-American pizza at least once a week, and children the world over delight in films by an Eastern European, Jewish American named Steven Spielberg. The American-accented brand of English is the closest thing we have to a universal language, while the French, obsessed with defending “Francophonie” and dreaming of a world united by their tongue, erect protective linguistic barriers, not understanding that this isolates them instead of preserving their culture. What France should seek to preserve—once it has conceded defeat in the language battle—is the context and originality of its message, not its medium.

France’s struggle with globalization is complicated by its people’s high quality of life. Most of the French feel they have little to gain and much to lose from globalization—the space and beautiful diversity of their countryside, the quality of their food and wine, and the respect for tradition. Why risk all these unique pleasures for the sake of an uncertain competition in a global world? The temptation for many Frenchmen is to retreat into the protective bubble of the good life.

TOPPLING THE GIANT

The end of the Cold War only reinforced French envy of America. They resent the global reach of America’s power and Washington’s presumption to speak in the name of the international community. Unlike the pragmatic British or the historically guilt-ridden Germans, the French feel that they, like the United States, carry a universal message. Remember that France, like the United States, is the font of ideas about “the rights of man,” liberty, equality, and fraternity. French frustrations are exacerbated by the mixture of benign neglect, sheer indifference, and mild irritation with which Washington considers Paris’ initiatives. In the absence of the unifying threat posed by the Soviet Union, Franco-American tensions can be eased only by shared interests. In the short run, France’s jealousy of America will be muted by the political constraints imposed on it by a united Europe, the other members of which do not share France’s feelings. The French know all too well that their secret dream—to build a Europe that will challenge the United States—is the nightmare of their continental partners. By openly expressing its differences with America, over the Middle East for example, Paris more often than not isolates itself from London and Bonn, not to mention the rest of the European Union. There are, however, subtle issues on which France can tilt Europe against America. If France is alone in supporting Iraq, for example, on Iran the rest of Europe is on its side and against the United States.

On security matters, Paris and Washington are at once allies and competitors. France’s ambition to create a genuine European foreign and security policy, although formally welcomed by Washington, clashes with the United States’ inclination to take the lead. France well knows that its long-term European ambitions will require it to rejoin NATO and give up on trying to attain some special status. France understands that more Europe tomorrow means more NATO today—a bitter pill, since expanding the alliance could reinforce the U.S. monopoly on security. But there is no alternative, since Europe lacks the political will to take on such a large commitment alone. In fact, the French have come to see any expansion of NATO without a corresponding widening of the European Union as an American attempt to preclude any specifically European initiatives in the security field.

In Paris, the peaceful end to the most recent crisis in the Persian Gulf was considered a triumph of French diplomacy over American belligerence. But it was a cosmetic victory, since Saddam Hussein’s receptiveness to diplomacy was certainly the result of his fear of being bombed by America. The neat division of labor that France and the United States enjoyed in the Middle East in the 1970s—France in Baghdad, America in Tehran—did not exist this time around. U.S. and French policies over Iraq are antithetical—the French eschew military options, and the Americans show little faith in diplomacy. This essential difference will not disappear and could rebound at the first opportunity—most probably when Saddam takes his next adventure.

Exploiting its position as a permanent member of the U.N. Security Council, France can present itself as an alternative Western voice to the nations of the Third World. In the Middle East, for example, Benjamin Netanyahu’s election and the resulting stall in the peace process has given a new legitimacy to Europe’s and in particular France’s role as an honest broker between Arabs and Israelis. Not content with merely bankrolling a peace process led by others, France intends to play a more active role, political as well as economic, complementing the United States but not replacing it. But the French cannot afford to balance America’s pro-Israeli position simply by being pro-Arab. France must demonstrate that it is serious about peace. It has certain advantages: unlike the United States, it is not a prisoner of domestic politics. If Paris cannot make peace, it can at least facilitate it.

On the African continent, the French must admit that they need Washington’s clout, just as Washington must admit that it needs France’s experience and presence. Africa brings out the best and the worst in the French. France is per capita the largest donor of foreign aid in the world after Japan, and well ahead of most European countries. But French money has gone more to regimes and leaders than to the African people. Rivals in economic terms, Paris and Washington are necessary geopolitical partners in this area. The United States has been keen to reassure the French that America has no secret agenda, no ambition to become Africa’s gendarme. In fact, the French are starting to realize that their views on the continent’s future converge with those of the Americans. Both fear regional destabilization, as in the new Democratic Republic of the Congo, formerly Zaire.

LOST IN THE CROWD

Although “Europe” does not yet exist in security and diplomatic terms, it is very real in economic and commercial terms, an actor whose power and influence will be strengthened by the coming of the euro. This is the only hope for the Europeans to balance America—only in the monetary field does a new bipolarity seem within reach. There is an irony here: The only card with which France can challenge American hegemony is Europe, and to play it, Paris must abandon much of its sovereignty.

For the Germans, European unification has been, together with their participation in NATO, the way to sever their links with their Nazi past, to erase the grim legacy of that dark period. For the Italians, always in search of domestic stability and a way to overcome their low self-esteem, Europe provides legitimacy, allowing them to triumph over their doubts about themselves and the credibility of their nation-state. For France, however, Europe—in its various forms, from the confederal model favored by de Gaulle to the federal one preferred by Francois Mitterrand—has been at the very heart of the French nationalist project, a way to pursue France’s past glory and power by multiplying its influence. For France to remain France, it must become Europe. Leaders of the left and the right, once in power, have strictly adhered to the European credo. France’s allegiance to the cause of Europe is now focused on the achievement of a common currency. To create a common European identity, to strengthen the voice of Europe in the world, to forge a new economic power, there is only one answer: the euro.

Yet for all of France’s devotion to the European ideal, one can sense its apprehensions. Beyond their fear of having created a technocratic monster, too intrusive for some, too impotent for others, the French worry about their country’s place within this new and enlarged Europe. In 1992, the debate about the Maastricht referendum was really a debate about Germany. Did the treaty offer the best guarantee against the potential threat of a reunited and powerful Germany, or would it lead to German supremacy in Europe? Does France run the danger of being squeezed between an economically dynamic Britain and an ever more powerful Germany? The city of London has recovered its old financial power, bursting with energy and activity. Berlin, once torn, will soon become not just the capital of the new Germany, but the capital of the new Europe. But Paris, some French fear, is in danger of becoming a new Rome, a pleasant and beautiful metropolis but one that is mainly a museum of its own past.

For now it seems that France’s best option is to continue to pay lip service to a united Europe and promote the Euro, while taking advantage of the lack of a diplomatic and military “Europe” to pursue an independent French foreign policy. This is the kind of Janus-faced exercise for which France certainly has the cunning and skill but which could prove dangerous for the future of Europe—if France were to be imitated by the Germans, for example.

Hesitant about their influence within an enlarged Europe, with a strong Germany at its center, the French are also anxious about the applicability of France’s model of state centralization to the requirements of a new Europe. There is a nagging fear in France that Britain’s laissez-faire economic model, built by Margaret Thatcher and largely preserved by Tony Blair’s New Labour, and Germany’s form of decentralized government are more modern than France’s old-fashioned statist recipe—a fear bolstered by the number of young French who are heading to Britain to find jobs in that dynamic economy. The state, once the pride of France, is now the main obstacle to adjustment and change.

L’ETAT, C’EST LA FRANCE

The French behave toward their state the same way that adolescents behave toward their parents: with a mixture of rebellion and submission. They criticize its heavy-handedness and inefficiency, but they appreciate its reassuring presence and protection. The spring 1997 legislative elections, which brought the Socialists to power, perfectly demonstrated this contradictory attitude. Socialist leader Lionel Jospin’s triumph showed that, on a moral and political level, the majority of the French want a less corrupt and more accountable government. At the same time, the electorate wants the state to protect the weakest, poorest elements of society and regulate the effects of the market. For example, Jospin’s plan to cut the maximum working week from 39 to 35 hours, against the wishes of many employers, may not make sense economically but is in tune with the feelings of most Frenchmen, who want to be protected by the state from long working hours. It does not matter to them if the idea that governments can create jobs better than market forces is outdated. France is a conservative society—its majority clings to the status quo.

The centrality of the French state is compounded by the society’s rigidity. France’s work force, for example, is decidedly less mobile than Britain’s. Too many people prefer to remain unemployed instead of moving to new towns or villages to fill jobs. This may contribute to family stability or the harmony of social life—which means that French families can always have Sunday lunch at grandma’s—but certainly not to the dynamism of the economy.

Criticisms of the state extend to those who incarnate it at the highest levels. The prestigious but stiflingly conformist civil service training school, the National School of Administration, is the focus of most complaints about the administration and political class, since its graduates have long monopolized the corridors of power. The French often accuse their civil servants of knowing neither the importance of social dialogue nor the way to govern in a genuinely democratic environment in which all citizens expect to be treated as equals. These attacks are almost reminiscent of their ancestors’ challenge to the nobility at the end of the ancien regime. If those who embody the state at the highest level cannot find an answer to unemployment and social injustice, the French ask, why should these mandarins enjoy virtual immunity from accountability?

Since the days of Alexis de Tocqueville, France has been described as a country forced into revolution by its inability to reform. Although today’s France is not about to revolt, it is suffering from a lack of hope for the future, which in large part explains the success of rightist groups like the National Front. The French economy is actually doing far better than the unemployment figures suggest: French industry is increasingly competitive, the trade balance is positive, inflation is down, and the franc is strong. Nevertheless, the French are morose. Their country is slowly and painfully transforming itself from a welfare state into a modern one, learning to live within its means. France has not chosen the easiest path to its goals and certainly not the most direct one.

IN SEARCH OF IDENTITY

Europe’s attempt to transcend its fratricidal quarrels by integrating its resources, economies, currencies, and political institutions into a quasi-federal state will serve it well in the global era. Regionalization is the best way to meet the challenges of globalization, because it makes states bigger, and bigger is better. But globalization reinforces the likelihood of fragmentation. Today, the need to express one’s difference in a global world leads to a desperate search for identity that can end in peaceful divorce between some nation-states and jingoistic tensions and bloody conflicts between others.

France is a perfect example of this identity dilemma. For decades the French have oscillated between celebrating their exceptionalism and proclaiming its end. Today France is torn more than ever between the desire to be a modern, normal country and the reflex to cling to the belief that France is not like other nations. The first choice presupposes openness, flexibility, and a secure sense of one’s identity. The second opposes globalization, is wary of a more unified Europe, and embraces anti-Americanism. But the second choice is no choice at all; protectionism would lead to isolation and decay.

France is probably sicker politically than is generally thought. The fact that large numbers of the French have thrown their support behind LePen’s National Front, which is highly represented in the country’s regional assemblies, indicates that the people of France have reached the end of their tether. Gripped by despair over their country’s high unemployment rate and declining importance in the world, they have begun to cast their lot with the exceptionalists, in a wistful but dangerous attempt to recapture France’s past glory. The moderate right is falling by the wayside, incapable of producing a message that will resonate with the masses like LePen’s and increasingly co-opted by it. The left and the Socialists, though in power, must contend with the fragility of their own coalitions. Corruption—and the threat that it will be exposed—hangs like the sword of Damocles over the heads of politicians on both sides. All of this combines to coarsen France’s political life and plunge the country further into its depression.

Yet despite the weaknesses, there is hope for France. The exceptionalists may be making gains, but for the time being, they are in the minority. Indeed, the National Front has lost its only seat in Parliament. And the more successfully France’s internal problems, particularly its unemployment, are tackled, the less political and social discontent men like LePen will have to exploit.

France has surmounted crises worse than this current crisis of confidence. Its long history will ultimately guarantee its stability. The land of Liberte, Egalite, Fraternite will not soon cede all of that for an imaginary kingdom of French supremacy, for its citizens know the despair that would bring. The French will come to realize that globalization, that most feared bogeyman on the streets of Paris, will not bring France’s demise but rather force it to hone its skills and refurbish its message. A more unified Europe will not smother it but in fact give it new purpose, allowing it to determine its own destiny in the world far better than it could do alone. The depression will subside. In the end, France will endure.

DOMINIQUE MOÏSI is Deputy Director of the French Institute for International Relations and Editor in Chief of Politique Etrangere.

****************

As America Retreats, Macron Steps Up

By Natalie Nougayrède (09-10/2012)

the Marquis de Lafayette’s help in the American Revolution to France’s gift of the Statue of Liberty and up through the shared fight in two world wars—the U.S.-French relationship has always been complicated. During the Cold War, French President Charles de Gaulle sided with the United States when it mattered, as during the 1962 Cuban missile crisis. But he also clashed with U.S. leaders as he sought to assert French autonomy within NATO and position his country outside the U.S.-Soviet rivalry. In the 1980s, U.S. President Ronald Reagan’s free-market policies made many French cringe (they tended to overlook his successful efforts to win the Cold War). But his French counterpart, François Mitterrand, also stood up to the Soviet Union, memorably declaring in 1983, “The pacifists are in the West, but the missiles are in the East.” After U.S. President George W. Bush ordered the invasion of Iraq, the United States’ popularity in France hit rock bottom. Things got so bad that a 2003 poll found that 33 percent of French hoped that the United States would lose to Saddam Hussein. It didn’t help that Americans had started calling the French “cheese-eating surrender monkeys” and sporting “First Iraq, then France” bumper stickers on their cars. Yet U.S.-French relations survived the disagreement over Iraq, with French President Jacques Chirac successfully seeking Bush’s support for a joint effort to get Syrian troops to withdraw from Lebanon in 2005.

The election of Barack Obama certainly swayed French public opinion. By the summer of 2009, according to a survey by the Pew Research Center, the United States’ favorability rating in France had soared to 75 percent (the highest score in Europe), up from 42 percent in 2003. But relations between Obama and French President Nicolas Sarkozy were awkward. Sarkozy found his American counterpart cold, and Obama joked about Sarkozy’s looks and his fast speech. Tensions over Iran went deeper: the French were wary of Obama’s outstretched hand and pushed for harsher sanctions. The NATO intervention in Libya was another stumbling block, with Sarkozy frustrated by Obama’s decision to withdraw U.S. bombers ten days into the operation.

Then came Donald Trump, a U.S. president like no other. During last fall’s U.S. campaign, France’s then president, the Socialist François Hollande, spoke for many of his compatriots when he said that Trump’s “excesses” made him want to “throw up.” On the right, Bruno Le Maire (who has since become France’s finance minister) called Trump “a dangerous man.” Days after Trump’s election, a survey found that 75 percent of French held a negative opinion of the incoming U.S. president. Most were convinced that he would damage U.S.-European relations and threaten world peace. Even half of the supporters of the far-right French presidential candidate, Marine Le Pen, opposed Trump, despite sharing many of his views on Islam, immigration, and trade.

Yet behind this widespread revulsion lies a diplomatic opportunity. With the United States looking inward and Trump having torn up the traditional foreign policy rule book, France’s new president, Emmanuel Macron, is seeking to reinvigorate the European project as a way of restoring French leadership. French power is no substitute for American power, of course. But with the United States’ image, global role, and reliability newly uncertain, Europeans feel a void that someone must fill—and France thinks it should at least try to do just that.

ENTRE NOUS

France and the United States have historically offered up similar but competing messages to the world: “American exceptionalism” is matched by France’s claim of being “the birthplace of human rights.” As Sarkozy once quipped, the two countries “are separated by common values.” France and the United States may not always see eye to eye on policy, but they both stand for humanistic values harking back to the Enlightenment. Against that backdrop, Trump’s blunt abandonment of even the pretense of defending the liberal international order and its accompanying body of human rights conventions has marked a watershed.

Trump’s style is also anathema to the French. The view from Paris is that Trump is a vulgar plutocrat who came to office by pandering to the unsophisticated masses and who might leave office early in scandal. His foreign policy positions, in their view, alternate between 1930s-style isolationism and trigger-happy unilateralism. As tempting as it may be for the French to look down their noses at the United States, however, they know that their country is not immune to right-wing populism: in France’s presidential runoff in May, Le Pen received more than ten million votes, a third of the total.

France feels as much discomfort as it does smugness.

But in the wake of Macron’s decisive victory over Le Pen, the French have rightly felt a sense of pride for having slowed down, or perhaps even halted, the march of populism across Europe, especially when across the Atlantic, Trump’s America looks like something out of Ubu Roi, the nineteenth-century French satirical play about an obscene king. But anxieties persist, and with the destiny of the West seemingly at stake, France feels as much discomfort as it does smugness.

Still, to a certain degree, the country is adopting a wait-and-see approach to Trump. His election has not brought the French out on the streets. There have been no demonstrations with such slogans as Vive la France! À bas l’Amérique de Trump! (Long live France! Down with Trump’s America!). Nor have the French seized on Trump’s disregard for NATO as a pretext to revive past grudges against the alliance, which some French saw as a vehicle for American imperial domination. De Gaulle has long ago turned in his grave: no official in Paris wants to undo France’s 2009 return to NATO’s integrated military structure, which he had pulled out of in 1966. Nor has Trump’s presidency sparked a groundswell of hostility toward the United States as a whole. It’s his personality, not his country, that draws so much contempt. This is good news for any future U.S. president who decides to revive the transatlantic link.

To be sure, anti-Americanism hasn’t vanished from France. It’s still present on both extremes of the political spectrum. Jean-Luc Mélenchon, the former Trotskyist who won nearly 20 percent of the vote in the first round of this year’s presidential election, loves to rant against U.S. policies while evincing little discomfort with those of various dictators. Le Pen, for her part, was seen sipping coffee in Trump Tower during her campaign (without meeting the man), and she did applaud his election (“Congratulations to the American people, free!” she tweeted). But her party’s nationalist ideology, as well as French opinion polls showing a deep dislike for Trump, made it hard for her to speak of the prospect of a Franco-American love fest. Instead, she chose to accentuate her fondness for Russian President Vladimir Putin. Setting aside these populists, most French distinguish between Trump, whom they see as an aberration, and the United States’ institutions, on which their hopes still rest.

But even though many French look back at Obama with nostalgia—so much so that Macron sought out and received his endorsement—he was not universally loved inside the Élysée Palace, the official home of France’s president. In fact, it is hard to overstate how livid the French foreign policy establishment was with Obama’s hesitant decision-making style, particularly when it came to Syria. The paroxysm came in August 2013, when Obama, having warned Syria’s Bashar al-Assad that the use of chemical weapons would represent the crossing of a “redline,” prepared to enforce it with an air strike when Assad did just that. Rafale fighter jets were ready to take off for a joint U.S.-French operation that French officials thought would set the stage for a major shift in the Syrian civil war and possibly lead Assad to accept a negotiated settlement. But within hours, Obama made a massive U-turn, declining to intervene and thus failing to carry out his own threat.

As the ensuing years have made clear, the prolongation of the Syrian conflict has not only produced untold human suffering; it has also inflicted severe damage on Europe, with the resulting terrorism and migration fueling the rise of populism. It was that moment in 2013, and not Trump’s election, that made Paris realize that it could no longer count on its ally across the Atlantic. Obama, with his advertised “pivot” to Asia, was already seen as aloof from Europe, but now France’s decision-makers learned that the White House could demonstrate total disregard for the objections of a close ally, and that it could go back on its word in ways that harmed European interests and international norms.

Macron was a senior aide to Hollande in the Élysée when these events unfolded, and they left deep traces on his own thinking about Europe and the United States. In an interview in June, he drew an explicit link between Obama’s turnaround in Syria and Putin’s aggression in Ukraine, which shattered Europe’s security architecture. “When you draw redlines, if you don’t know how to get them respected, you decide to be weak,” he said. He went on: “What emboldened Putin to act in other theaters of operation? The fact that he saw he had in front of him people who had redlines but didn’t enforce them.”

HOW TO TREAT TRUMP

Immediately after Macron took office, fresh from an electoral battle against political forces that Trump seemed ready to promote, he made it clear he would not submit to the U.S. president. At a NATO meeting on May 25, Macron managed to fend off Trump’s apparent attempt to dominate him during a handshake. He wasted no time in capitalizing on the episode. “That’s how you ensure you are respected,” he told reporters. “You have to show you won’t make small concessions—not even symbolic ones.” Macron went on to deliver a remarkable video address to the American people in response to Trump’s withdrawal from the Paris climate agreement, calling on U.S. scientists, engineers, and “responsible citizens” to “find a second homeland” in France. And he launched a campaign to “make the planet great again” that gained traction on social media. For a moment, it seemed as if Macron would single-handedly take on Trump and cast himself as the leader of Western liberalism.

In Paris, foreign policy grandees took to the television studios, barely hiding their excitement: now was the time to demonstrate a Gaullist independence, they claimed. Dominique de Villepin, a former foreign minister and former prime minister, argued that France needed to be put back on its traditional track of “mediating” and “balancing” between powers. A debate had been raging in Parisian circles about whether Hollande—and, before him, Sarkozy—had been too “Atlanticist” in orientation, too dangerously aligned with the United States. This hardly matched the facts, considering the bilateral tensions that existed under both Sarkozy and Hollande. But Macron, it was thought, would offer a welcome course correction.

But those who hoped for a full-on clash with the United States would be disappointed. Macron, it turns out, has recognized that anti-Trumpism can hardly serve as the animating idea behind French foreign policy. He has chosen his words carefully, eager to preserve relations with the White House. Unlike German Chancellor Angela Merkel, who has publicly confronted Trump over his lack of commitment to Western values, Macron has aimed narrowly—for instance, criticizing the Trump administration’s stance on climate change rather than declaring, as Merkel did, that the United States can no longer be relied on. In the run-up to the federal election in Germany in September, Merkel has no doubt been aware of the risks of appearing to agree with Trump on anything. Macron is much less constrained. In May, after meeting with Trump at the G-7 summit, he said that despite their differences, he found Trump “pragmatic” and “someone who listens and who is willing to work.” Macron even went so far as to invite Trump to this year’s Bastille Day festivities in Paris. Macron’s team framed the gesture as aimed at honoring the United States’ long-standing role in Europe, but it was hard not to see it as an attempt to generate good chemistry with Trump.

For Macron, antagonizing the new U.S. leader simply carries too many downsides.

For Macron, antagonizing the new U.S. leader simply carries too many downsides—above all, the prospect of jeopardizing cooperation on counterterrorism. French officials see national security as paramount. For years, France has been positioning itself as the United States’ most active European ally when it comes to counterterrorism, and since the 2015 terrorist attacks in Paris and the 2016 one in Nice, that has proved truer than ever. It’s no mystery why: with its constrained defense resources, France can ill afford to dispense with U.S. help in the fight against the Islamic State (or ISIS) and other terrorist groups, whether in the Middle East or the Sahel. Trump’s election will not change the centrality of counterterrorism in the relationship. Indeed, Macron has declared counterterrorism his “number one priority,” and his first meeting with Trump centered on the fight against ISIS. But what Trump’s election will likely change is the way France manages the relationship. Like other U.S. allies, France is struggling to navigate an increasingly indecipherable Washington power structure.

EUROVISION

Instead of seeing Trump’s election as a reason to completely distance France from its ally across the Atlantic, Macron is looking for ways to boost France’s standing in its immediate neighborhood. French influence in Europe has waned in recent years, in turn weakening France’s position on the broader international stage. During the Obama era, it was Germany that served as the United States’ preferred interlocutor. From a French standpoint, that was a highly unbalanced arrangement. Ever since its creation 60 years ago, the European project has been seen in Paris as an amplifier of French influence, not an instrument of its marginalization. Remember that it was only after France lost its empire in 1962, when it withdrew from Algeria, that de Gaulle fully committed to a common European endeavour. (He signed a friendship treaty with West Germany the very next year.)

In an important campaign speech in March, Macron described his vision of France’s place in the shifting global landscape:

To those who have become accustomed to waiting for solutions to their problems from the other side of the Atlantic, I believe that developments in U.S. foreign policy clearly show that we have changed eras. Of course, the alliance with the United States is and remains fundamental, at the strategic, intelligence, and operational levels. . . . But for now, the Americans seem to want to focus on themselves. The current unpredictability of U.S. foreign policy is calling into question some of our points of reference, while a wide space has been left open for the politics of power and fait accompli, in Europe, in the Middle East, and also in Asia. So it is up to us to act where our interests are at stake and to find partners with whom we will work to substitute stability and peace for chaos and violence.

That Macron hasn’t publicly repeated those thoughts in so many words since his election does not mean they have changed: rather, he recognizes the diplomatic constraints of being in office. But while somewhat toning down his rhetoric, he has already started putting some of these ideas into practice.

The centerpiece of Macron’s plan for Europe is to usher in a new era of continental defense cooperation. The French president has supported the creation of a “European defense fund” to pay for continent-wide projects, and he envisages ad hoc European coalitions for military interventions in and outside Europe. On this front, the French think it’s only natural that their country take the lead. The United Kingdom has become obsessively inward-looking—almost a disappearing act, to France’s deep regret. In continental Europe, France remains the top military power, and the only one with a nuclear deterrent and a permanent seat on the UN Security Council. For historical reasons, Germany is still reluctant to expand its military and put soldiers in harm’s way. France has no such qualms, and its political culture allows the president to act militarily without much parliamentary oversight.

But Macron recognizes that France cannot go it alone, and that Germany is key to what he likes to describe as a “European renaissance.” His team is considering taking steps toward deeper integration of the eurozone, although much will depend on the outcome of the German election, as well as on Macron’s capacity to implement economic reforms at home. In the future, expect Macron to showcase his closeness to Merkel, as when he went to great lengths to support the chancellor’s refugee policies—ones Trump has repeatedly castigated. Reviving the so-called Franco-German engine is crucial to the continent’s newfound sense of self-confidence, momentum that Macron wants to capitalize on.

Macron has also called for reform of the European Union, which he sees as ineffective and out of touch. In his view, it must build better defenses against terrorism, Russian aggression, and abusive trade practices (including China’s). Macron had drawn up this wish list well before the U.S. election, but Trump’s maverick streak has made those steps even more urgent, because Europe now questions the United States’ traditional security guarantees and lacks a reliable partner on free trade.

NOW WHAT?

Trump is arguably as much an opportunity for Europe as he is a problem. But those hoping that Europe will weather the United States’ turn inward easily should manage their expectations. For starters, Europe can hardly fill the shoes of the United States. There is no such thing as a European nuclear umbrella on offer, and talk of a “European army” remains lofty. Rather, Europeans will take more modest steps, such as pooling their resources for the joint procurement of military equipment. Besides, there are powerful historical hang-ups that haven’t entirely disappeared. Macron knows well that it was France, not Germany, that rejected plans for a European army in 1954.

Given all the threats to Europe today—Brexit, Putin’s aggression, Turkey’s authoritarian turn, and the specter of terrorism—Europe can only try to mitigate some of the consequences of the Trump phenomenon. On this, Macron would surely agree with how one former Obama administration official framed things for me: “Europe needs to hold the fort for as long as Trump remains in office.”

Frans Timmermans, the deputy leader of the European Commission, once said that there are two kinds of countries in Europe: “small ones, and those who don’t know yet they are small.” The French would like to renew their country’s sense of grandeur, but France is no superpower. The contrast with Trump may make them feel good about themselves. But as Macron reflects on what he has called “the strategic void” left by the United States’ retreat, he knows that he has no other option but to address Europe’s weaknesses if he wants France’s voice to matter. In other words, he must hedge against “America first” by focusing on Europe first.

NATALIE NOUGAYRÈDE is a columnist for The Guardian.

*************

Macron’s Flawed Vision for Europe

•Persistent Divisions Will Preclude His Dreams of Global Power

By Francis J. Gavin and Alina Polyakova

On May 11, 1962, U.S. President John F. Kennedy hosted an extraordinary gathering of American cultural talent to welcome France’s minister of culture, André Malraux. The dinner—which included luminaries such as the novelist Saul Bellow, the painter Mark Rothko, the playwright Arthur Miller, and the violinist Isaac Stern—was a celebration of the long-standing historical ties between the United States and France. Only hours before this glamorous fete, however, Kennedy, Malraux, and the French ambassador to the United States had a sharp exchange over French President Charles de Gaulle’s increasingly strident critiques of U.S. policy and accompanying demands for strategic autonomy.

De Gaulle’s complaints included criticism of the United States’ strategy during the Berlin crisis, the primacy of the dollar in the international economy, and U.S. support for the United Kingdom’s application to the European Economic Community. The French president, Kennedy remarked, appeared to want both U.S. protection and the unfettered ability to chart his country’s own path, “a Europe beyond our influence—yet counting on us,” as his national security adviser, McGeorge Bundy, summarized him saying. The French president should be careful what he wishes for, Kennedy added, since “Americans would be glad to take the U.S. out of Europe if that was what the Europeans wanted.” When Malraux proclaimed that the United States didn’t dare leave, the president retorted that the United States had “done it twice” already, referring to the United States’ withdrawal after both world wars.

The discord was only partially alleviated by the president’s toast, which Kennedy claimed would be the “first speech about relations between France and the United States that does not include a tribute to General Lafayette.” Instead, Kennedy highlighted the first president to live in the White House, John Adams, who “asked that on his gravestone be written, ‘He kept the peace with France.’” Ultimately, Malraux was proved right: de Gaulle continued to undermine the United States, yet successive U.S. administrations, although tempted, did not withdraw the United States’ security umbrella.

On January 19, 2022, French President Emmanuel Macron took a page from de Gaulle in a speech before the European Parliament, at the beginning of France’s six month presidency of the Council of the European Union, calling for Europe to make “its unique and strong voice heard” in the continent’s security. For Macron, strategic autonomy means a Europe with its own place in the world and its own ability to shape world events, even if it that means pursuing a security pact with Russia as the U.S. pushes for sanctions. Similar to his predecessor de Gaulle, Macron does not want Europe—or France—to be a powerless observer in a world increasingly defined by a competition for influence between a rising China and the United States.

It may seem like not much has changed since Kennedy’s meeting with Malraux given that France and the United States are still arguing over Europe’s independence. But today’s geopolitical reality is not that of the 1960s. The world is no longer defined by Cold War struggles between two superpowers; the United States now sees China and the Indo-Pacific as its greatest foreign policy priority, and the transatlantic alliance faces many challenges, such as addressing climate change and regulating new digital technologies, that it was not designed to tackle.

But although Macron is right to push Europeans to evaluate the continent’s place in the world, he has yet to lay out the priorities that should guide Europe, nor has he put forth a strategy for expanding the continent’s capacities so that it can act on them. Macron’s vision is more of a laundry list, addressing everything from increased multilateralism to counterterrorism strategies to talks about beefing up the continent’s security. Some proposals seem contradictory, such as the desire for a France that possesses “the ability to rank and have influence among other nations,” a country in which the French would be the “master of our own destiny,” yet also a country in which “our independent decision-making is fully compatible with our unwavering solidarity with our European partners.” Other ideas seem problematic and unlikely to find wide adherence, such as Macron’s suggestion that “there can be no defense and security project of European citizens without political vision seeking to advance gradual rebuilding of confidence with Russia.”

This vision assumes that a continent with a long history of divisions is now united on its defense and foreign policy. But a cursory look at the recent debates on Russia, China, and even the United States shows a lack of strategic coherence among European states. Macron’s vision, in short, could splinter Europe and dilute its capabilities and focus, all while playing into the United States’ worst instincts to disengage from the transatlantic alliance to focus on China.

SAME AS IT EVER WAS?

All sovereign states value their autonomy; the real historical puzzle is understanding those moments when states subsume some element of their freedom of action for the common good. This is what is so remarkable about NATO. Most people expected the United States to bring its military forces home after the end of World War II, as it had never participated in a peacetime military alliance in its history. But the alliance’s transatlantic security arrangements have lasted almost eight decades, weathering profound changes in the international system from the fall of the Soviet Union to the rise of China.

To be sure, there have been moments of tension and even crisis, dating from the Suez crisis in 1956 to the United States’ invasion of Iraq in 2003. The larger transatlantic relationship has been plagued by disagreements over who controls nuclear weapons, trade and monetary policy, gas pipelines, and now technology regulation. Sharp disagreements are a feature, not a bug, of transatlantic relations, and the ability to manage these conflicts is the unique genius of the Western alliance. Strategic autonomy—where each state pursues its own national interests—is and always has been the easiest answer but not the most effective one.

Europe has been more peaceful than anyone could have imagined when NATO was founded in 1949. Its divergent economies, societies, and governments are integrated in ways that would have been unthinkable when the Treaty of Rome, which brought about the creation of the European Economic Community, the forerunner of the European Union, was signed in 1957. The EU’s population is highly educated, technologically advanced, and by some measures as rich as, if not richer than, those of the United States and China. Developing its own grand strategy and providing for its own security would be a natural next step.

The United States should not dismiss the potential upsides of greater European autonomy.

Such autonomy is especially appealing at a time when the United States’ reputation on the continent has been damaged. The erratic policies of the Trump administration and the decision to withdraw from Afghanistan raised questions about the United States’ reliability as a strategic partner. Then the AUKUS submarine deal the Biden administration brokered with Australia and the United Kingdom raised hackles in Paris: it deprived the French of a lucrative contract without, allegedly, giving the Macron government advance notice. No wonder many European leaders welcome a compelling, coherent, and widely shared strategic vision.

The United States should not dismiss the potential upsides of greater European autonomy. It would be far easier for the United States to contain China if Europe assumed more responsibility for its collective security. Indeed, the U.S. architects of the postwar order in Europe committed to the continent in the hope that the U.S. presence eventually would become unnecessary. The U.S. commitment to Europe not only has been expensive; it also has limited the United States’ own strategic autonomy, given the extensive commitments it has made to European countries. The consequences of this interdependence are playing out as the United States negotiates with Russia on the future of European security in Ukraine. It is striking that Europe has been unable to deter aggression on its own continent without U.S. involvement.

WRONG SOLUTION, WRONG PROBLEM

Both Europe and the United States would benefit, then, from the Europeans’ stepping up. But Macron’s proposal to speak on behalf of Europe while demanding a leading role in hot spots around the world is the wrong solution to the problems he has identified. China’s rise, Russian aggression, the weakening of democracy, global warming, technology regulation, and public health all demand collective action, and that is the opposite of what the French president appears to be proposing. Rather than going it alone, Europeans would be better off working together with the United States on a few key priorities. For example, they should identify where they could invest more to augment defense capabilities in their neighborhood and allow the United States to focus on shared economic and political challenges emerging from East Asia, in particular by supporting U.S. efforts to compete with China.

Macron’s proposed strategy, in contrast, embraces all of the world’s major geopolitical challenges while also seeking to lead on the great transnational challenges of the day. The French president has made clear that European states should assume more responsibility for the defense of the continent. He has also declared France to be an Indo-Pacific power. France has not abandoned its focus on terrorism, which along with its colonial-era ties drives it to take a keen interest in the politics of the Sahel and the greater Middle East. Meanwhile, France and Europe proclaim the climate crisis to be the world’s most existential challenge. All this must be confronted while buttressing democracy and strengthening the liberal economic order in the midst of the calamitous COVID-19 pandemic. This agenda would be challenging, even impossible, for a state far more powerful than France or even for Europe as a whole. Macron’s approach would result in a Europe that, instead of doing one or two things well, might do everything poorly.

France also does not speak for the EU, and in trying assume that role, it threatens to fracture the continent further. There is great disagreement within Europe over how to deal with the array of challenges it faces, but especially when it comes to security. The EU has put forth a number of defense initiatives, including the Permanent Structured Cooperation (PESCO), a set of initiatives created four years ago to heighten defense cooperation among participating EU member states; the European Defense Fund, which supports collaborative military research and development; and a potential European army, an old idea both Macron and former German Chancellor Angela Merkel revived in recent years. None of these ideas can get off the ground without European consensus on priorities, and that simply does not yet exist.

Take Russia. France wants to give Russia a say in European security: in his speech to the European Parliament Macron urged Europeans to “conduct their own dialogue” with Russia just as the Kremlin seems ready to invade Ukraine again. This latest call to go against U.S. led diplomatic efforts follows a 2019 initiative when Macron dispatched his defense and foreign ministers to Moscow to explore ways of bringing the country back into the fold of industrialized nations, breaking a four-year freeze on such high-level diplomatic visits. Macron also advocates for taking stock of NATO, which he claims is experiencing “brain death.” In contrast, Poland and other NATO allies in close proximity to Russia want hardened defenses on their borders and a permanent U.S. troop presence—and with Russia mounting a potential reinvasion of Ukraine, those views seem justified.

It is dangerous to presume Europe is a stable, coherent actor on a positive trajectory.

The same divisions are reflected in the treatment of the United States. After the AUKUS fiasco, France views the United States as an unreliable partner that stabs allies in the back in the interest of defense contracts, whereas eastern European countries see it as an indispensable partner. Schisms also exist in regard to China. Former diplomat and French Finance Minister Bruno Le Maire has said that Europe wants to “engage” with China. Germany under Merkel sought a far-reaching investment deal with China, the Comprehensive Agreement on Investment (CAI), which was later suspended by the EU, and Italy joined China’s Belt and Road Initiative in 2019. Meanwhile, the Lithuanian government has told its own officials to stop using Chinese phones that it says contain censorship software, cozied up to Taiwan, and quit a Chinese-led regional forum. Romania, too, kicked Huawei out of its 5G networks and blocked deals for China to build nuclear reactors in the country.

Macron’s strategic autonomy also presumes that Europe is a stable, coherent actor on a positive trajectory. That is a dangerous assumption: after decades of impressive economic and political integration and institution building, the European project itself is under duress. From Brexit to democratic backsliding to uneven economic growth, European cohesion or stability cannot be taken for granted. Germany has new leadership for the first time in 16 years, and its future strategic orientation is uncertain. To be fair, Macron recognizes the desultory state of European affairs, and much of his strategy is a call for the continent to “wake up.” Yet his recommendations risk further fracturing Europe.

Macron’s vision could also spur the United States to reconsider its security guarantees. There is a mythology that the United States dislikes European autonomy, but a brief look at postwar history shows U.S. policymakers have long harbored a desire to leave the continent to its own devices. Presidents Harry Truman, Dwight Eisenhower, and even Kennedy saw the United States military commitment to Europe as temporary, a bridge to a future when Europe could defend itself. After the Cold War ended, every administration from Clinton through Obama encouraged Europe to take a greater role in providing for its own security. Many in the United States would like nothing better than for Europe to take care of its own defense, a worrying attitude at a time when Europe is increasingly fractured and lacks the capabilities to meet various strategic challenges.

To be sure, a weak and divided Europe will not benefit the United States in the long term. Nor will a Europe that is rushing to grow up too fast, leaving itself dangerously vulnerable before it is able to defend itself. China and Russia would no doubt like nothing more.

TIME FOR A RETHINK

Macron is right that Europe needs to reevaluate its priorities and act on them. The European Union cannot continue to drift and depend entirely on a distant and distracted superpower for its security while standing on the sidelines. At a time when the U.S. position in the world is uncertain, a vigorous European effort to contribute to a strategy for the West would be most welcome.

Any new strategy, however, should be built on several principles. For one thing, Macron should make a greater effort to generate consensus on the most pressing security challenges. The threat presented by Russia provides an early but crucial test in a way that goes beyond immediate military decisions. For example, Europe depends on Russia for energy. Whether the continent is willing to explore serious efforts to end this dependence will reveal the outer limits of what individual nation-states are willing to sacrifice in exchange for reducing President Vladimir Putin’s leverage.

A new European strategy also cannot emerge solely from Paris. It will be Germany, with its economic power and historical legacy, whose actions will matter far more than France’s. And it is an open question whether Berlin can be enticed to contribute to a shared, forward-looking European strategy that goes beyond Merkel’s mercantilist legacy. On decisions ranging from Nord Stream 2 to engagement with China, the longest-serving chancellor was driven, despite her other virtues, by narrow domestic political and economic motivations rather than an outward-looking strategy that recognized new geopolitical dangers. For Europe to play a meaningful role in the world, Germany must be engaged and strategic.

Nor can the continent go it alone; it must involve non-European partners. This goes beyond the obvious need to coordinate with the United States. It is imperative to include the United Kingdom despite Brexit, which, after all, reflected the country’s own desire for greater say over its affairs. No European strategy—especially one advocating for increased autonomy—will have meaning without the capabilities to back it up. European countries, both collectively and individually, massively underinvest in their ability to defend themselves. The European Union spends an embarrassing 1.2 percent of its GDP on defense, less than one-third of what the United States spends. European states must spend more on their militaries. Finally, any European effort must establish priorities, including confronting a difficult question most Europeans avoid: What are they willing to fight and die for?