By Ella Koeze

In response to Russia’s invasion of Ukraine late last month, Western powers turned to an increasingly common playbook: imposing a broad range of sanctions that had immediate and devastating impacts on Russia’s economy, financial system and citizens.

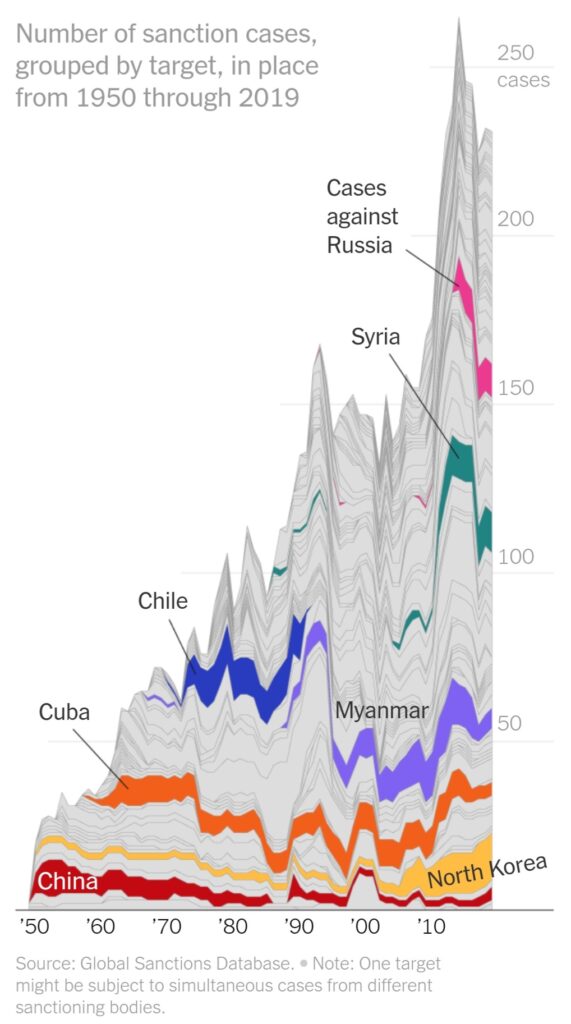

The use of these kinds of penalties has risen sharply in recent years, according to the Global Sanctions Database, a project from Drexel University that has become the most comprehensive tally of its kind.

The database includes more than 1,100 cases: instances when a sanction or a set of sanctions were ordered by a country or intergovernmental body against another country or organization. Some sanctions, including those against Cuba, have been in place for decades.

South Africa faced strict penalties during the apartheid era. In addition to combating military aggression, sanctions are often used to target human rights and other abuses. Iran was the target of a growing set of cases until a number were rescinded with the signing of the Iran nuclear deal.

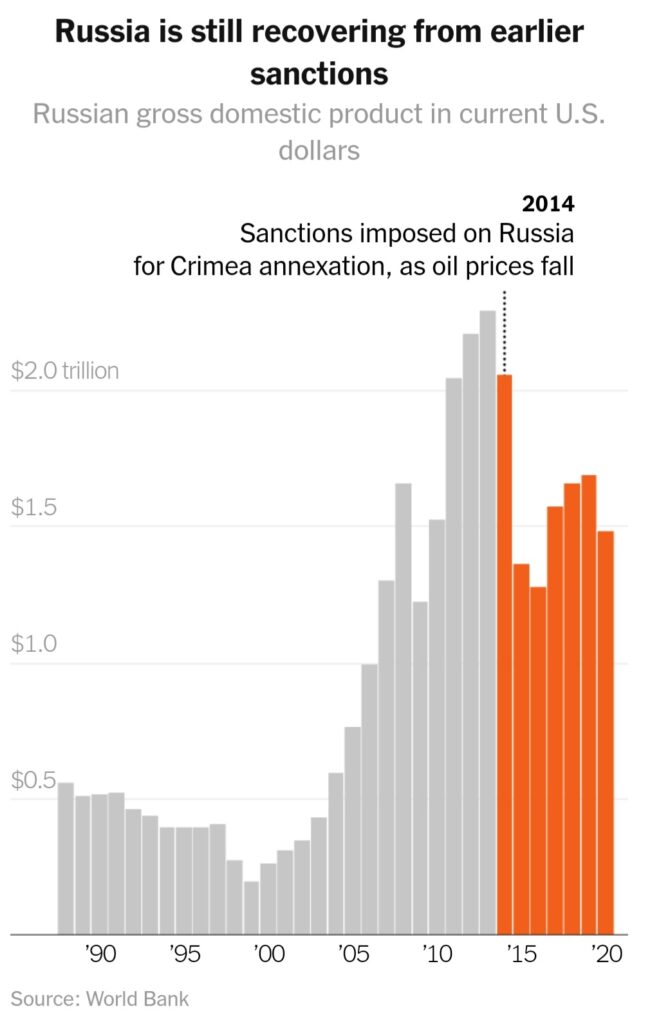

Russia was previously punished in 2014 when it invaded Crimea. Many of those provisions remain in place.

Constantinos Syropoulos and Yoto Yotov, trade economists and two of the researchers behind the database, suggested that one factor driving the popularity of sanctions could be a resistance to engaging in military conflict. The United States, for example, has long used sanctions as a foreign policy tool. But it has accelerated their use in the last 20 years, just as support waned for the costly and unpopular wars in Iraq and Afghanistan.

The United States is responsible for the most sanctions cases, accounting for 42 percent of those in place since 1950, according to Drexel’s data. Next is the European Union, with 12 percent, and the United Nations, 7 percent.

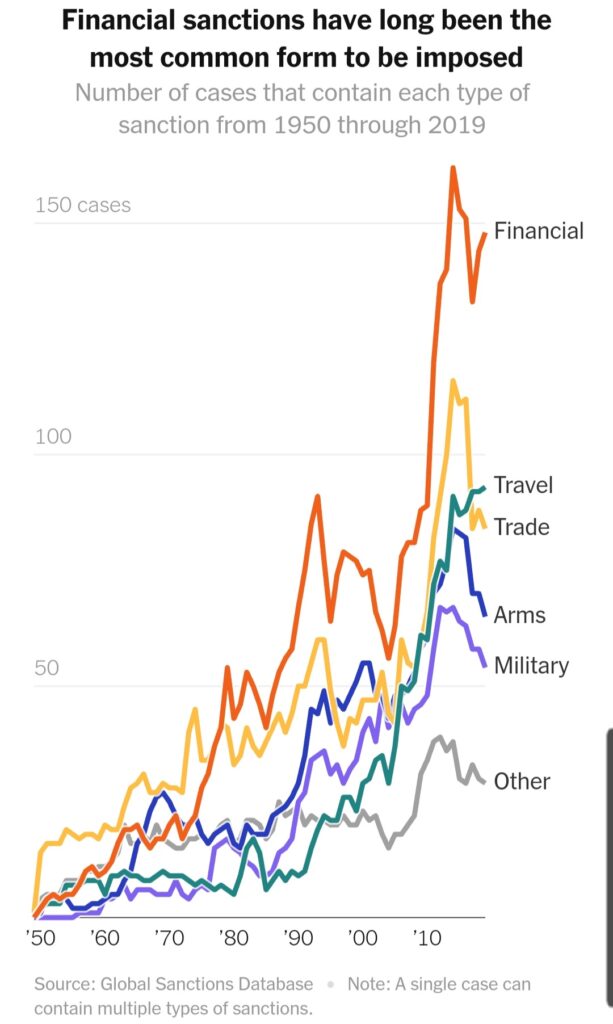

Sanctions have also become increasingly specific. The aim is often to directly punish responsible parties — without harming citizens of the target country, decimating its economy or jeopardizing valuable trade relationships with allied nations.

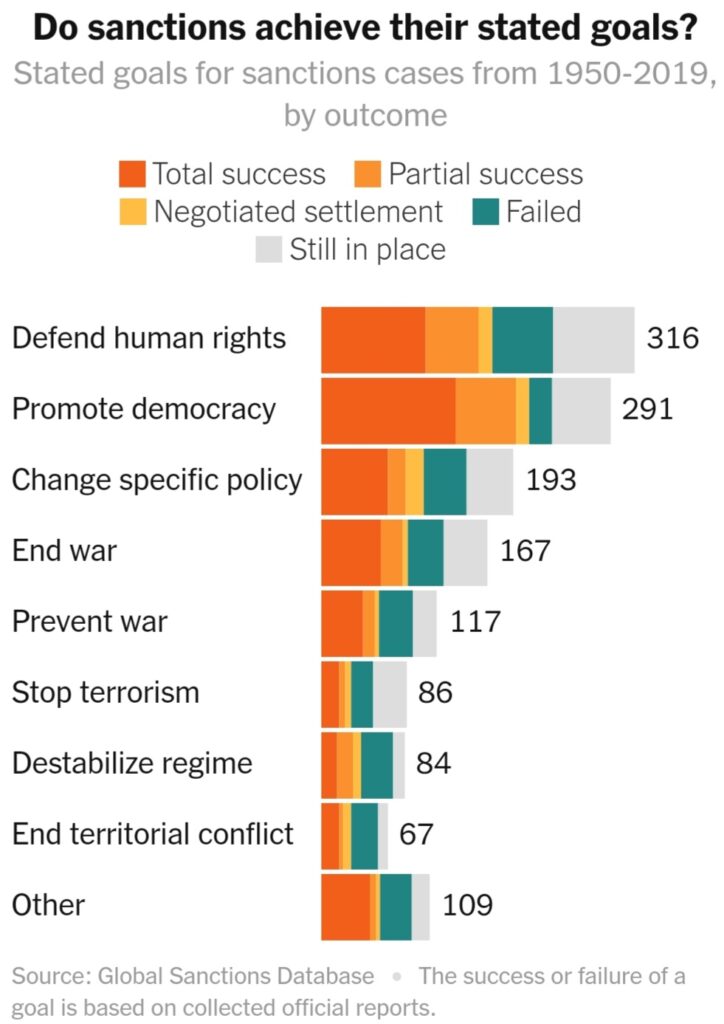

As their use has increased, so has the urgency of the question: Do sanctions work? “There is no doubt in our minds, sanctions are economically very, very painful,” said Mr. Yotov. But, he added, “this doesn’t imply necessarily that they’re going to reach their ultimate goals.”

To assess the success of sanctions in their database, the researchers compared stated policy goals for each case with determinations from government or official sources such as the United Nations on whether the goal was achieved. Using this framework, they found that about half of the stated goals in the sanctions cases were at least partly achieved, and about 35 percent were completely achieved. These estimates are roughly in line with previous research, though Mr. Yotov and Mr. Syropoulos cautioned that quantifying the objectives or the outcomes of sanctions inherently involved a degree of subjectivity and interpretation.

These numbers include only sanctions that were imposed, but sometimes a threat alone is enough to achieve a specific goal. Estimates from another database that contains instances of threatened and imposed sanctions through 2005 suggest that if cases when penalties were threatened are counted alongside cases when they are imposed, the success rate of sanctions overall is higher. And even when a goal is not achieved, enforcing sanctions can make future threats of sanctions more credible, said T. Clifton Morgan, a political scientist at Rice University and a lead researcher behind this database.

In the current crisis, the threat of sanctions did not prevent Russia’s invasion of Ukraine, and it’s too soon to say whether imposed ones will help encourage the war’s end. Determining what makes sanctions successful involves many factors, including how coordinated they are across countries and how important the underlying cause — in this case President Vladimir V. Putin’s desire to control Ukraine — is for the target country.

Whether or not they reach their stated goals, such penalties are often very effective at causing extreme economic pain and severely decreasing quality of life in the target country. Russians are experiencing this right now — as they did to a lesser extent after 2014, when the country’s G.D.P. contracted nearly 2 percent after sanctions were levied while global oil prices were falling.

In the current crisis, the first wave of sanctions against Russia was largely financial. The international assets of oligarchs and other powerful Russians within Mr. Putin’s inner circle were frozen and their foreign travel was limited. Russian banks were excluded from a critical communications system used for international transactions. These actions formed part of a wider strategy to cut off the means for Mr. Putin to finance his war effort.

As Russia has refused to change course in Ukraine, Western countries have ratcheted up their tactics, including blocking the sale of Russian oil and gas. Private companies like McDonald’s and credit card companies have also stopped operating in the country, wreaking even more havoc.

Russia’s economy has been struggling under the weight of these heavier penalties, and is expected to go into default, sending ripples around the world as oil prices and other costs rise.

The response to a pileup of sanctions is not always predictable. One concern Western leaders have had is that Russia may deepen its ties with China if it’s further cut off from the rest of the world. One example of that came last weekend, when Russia’s central bank said that some of the country’s financial institutions might begin using China’s credit card system after Visa and Mastercard stopped functioning there.

Sometimes sanctions can also have the counterintuitive effect of consolidating the power of an authoritarian government, according to Dursun Peksen, a political scientist at the University of Memphis. When a nation becomes isolated, he found, access to state resources becomes even more important, and elites unite behind the leader and quell opposition. Sanctions are often detrimental for human rights, democracy, gender equality, press freedom and public health in affected nations such as Iran and Cuba, Mr. Peksen’s research showed.

“Russia will become a lot more authoritarian, more isolated, and it’s the average Russian citizen that will incur the most cost,” he said. Ultimately, he added, when imposing sanctions “we have to strike a balance between political gain and civilian pain.”

Credit | New York Times