By Nicolas Florquin

Eolika, a Guyana-flagged cargo vessel, had already been detained in the port of Senegalese capital, Dakar due to ‘inconsistent’ declarations.

Authorities in the West African nation then searched the ship, seizing three containers of Italian manufactured ammunition worth an estimated US$5 million.

According to initial accounts, port authorities in La Spezia authorised the shipment, which was reportedly headed to the Dominican Republic.

But at the time of writing, it remained unclear why the vessel made the unexpected stop in Dakar, leading civil society groups to call for more transparency on the transfer.

The consignment highlights the fact that the international small arms trade is shrouded in ambiguity. Available statistics don’t capture all actual (as opposed to reported) transfers.

Yet it’s important to be able to measure the extent of the trade.

Our organisation, the Small Arms Survey, maintains a database on the transparency of global authorised small arms transfers: the Small Arms Trade Transparency Barometer.

Launched in 2003, the Barometer provides annual updates on states’ arms export reporting. This is a way to assess the transparency of the world’s major exporters of small arms, light weapons, as well as their parts, accessories, and ammunition.

A trade that lacks transparency

The 2021 edition found that the 50 exporters under review scored on average 12.61 points out of a possible 25.

While this score marginally increased compared with 2020, it remains low. It shows that the international community still has a long way to go in fostering openness in the arms trade.

The quality of data on the small arms trade in Africa is no exception. Information on ammunition transfers to the continent is particularly scarce.

Our 2020 trend analysis of the global authorized small arms trade, Trade Update 2020: An Eye on Ammunition Transfers to Africa, showed that African ammunition imports amounted to USD 97.7 million in 2017, or 42% of the continent’s total small arms imports.

This is not the full picture. The scope of the trade originating from the least transparent exporters is particularly difficult to assess.

Field research on ammunition used in conflict areas and export records compiled by commercial entities, reveal a broader range of ammunition transfers than what is reported by African states and their trading partners.

From authorised to diverted

The 2020 Trade Update also illustrates some of the ways in which authorised transfers can subsequently end up in the hands of unauthorised armed groups.

Such ‘diversion’ can occur when declared end users participate in unauthorized retransfers.

There are also often instances where armed groups and criminals manage to seize national stockpiles or capture weapons on the battlefield, sometimes shortly after the delivery of this material to the state entities.

For instance, in 2014, the UN Group of Experts monitoring the arms embargo on the Democratic Republic of Congo (DRC) documented the presence of heavy machine gun ammunition bearing markings that were consistent with Chinese manufacture in armed group arms caches in the country’s North Kivu province.

In its 2015 report, the Group of Experts established that this ammunition was originally part of a 2012 delivery of 12.7 × 108 mm ammunition from China to the Armed Forces of the DRC.

The transfer was not transparent in that it had not been notified to the United Nations Sanctions Committee. It therefore violated the exemption procedures established under the arms embargo on the DRC.

The case illustrates how rapidly –in less than two years– unreported ammunition transfers can be diverted into the illicit sphere.

Destabilising effects

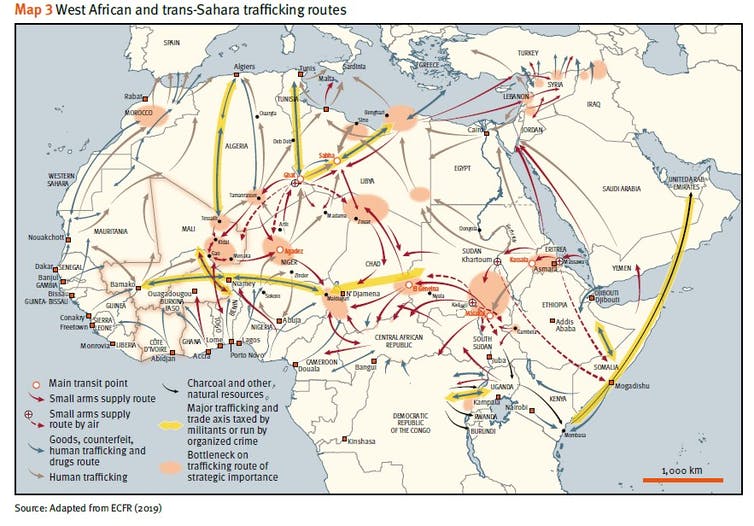

New illicit flows of arms and ammunition feed into existing trafficking networks, which in West Africa contribute to fuelling conflict and instability in several ways.

Small Arms Survey research in the tri-border region of Burkina Faso, Côte d’Ivoire, and Mali, for example, documented an increase in smuggling and trafficking activities due to growing local demand for illicit goods and firearms.

This demand is fuelled by banditry, communities’ need for self-defence, traditional hunters’ reliance on firearms, and artisanal and small-scale gold mining.

The growing trade is challenging states’ ability to monitor and control their borders.

Several governments in the region have sought to contain and respond to insecurity by increasing their reliance on local self-defence groups for providing community protection.

This raises concerns about the risk of excessive use of force, harsh punishments, or even extra-judicial killings.

Regional trafficking routes also extend well beyond local borders, and connect the Gulf of Guinea to the Sahara in the North and to Central and East Africa.

Some of the main smuggling and trafficking hubs are located in the Sahara–Sahel region, which has been particularly affected by conflict and the attacks of prominent terrorist-designated armed groups.

Security-focused responses to address these threats have also shown their limits. They tend to affect the livelihoods of local communities who depend on the informal cross border trade.

They also risk enticing smugglers into becoming involved in trafficking and other illicit activities for a living.

While the specific linkages between arms trafficking and insecurity are complex and context-specific, it is clear that illicit transfers to Africa have the potential to rapidly reach countries and regions affected by insecurity and armed violence.

Achieving more transparency in the small arms and ammunition trade would support better and more independent monitoring of the legal trade. This, in turn, would contribute to preventing its diversion to unauthorised users and traffickers.

Nicolas Florquin is the Head of Data & Analytics and Senior Researcher for the Small Arms Survey, Graduate Institute – Institut de hautes études internationales et du développement (IHEID), and Alaa Tartir, Senior Researcher and Coordinator of the Security Assessment in North Africa project at the Small Arms Survey, Graduate Institute – Institut de hautes études internationales et du développement (IHEID).

Credit | The Conversation