European leaders have set a target to end their reliance on Russian oil and gas “well before 2030,” which could lead to new market gains for Nigeria, Angola, Libya, and Algeria on liquified natural gas.

“It seems that Africa now is the most reliable alternative for these countries in Europe,” said Kennedy Chege, a researcher and doctoral candidate at the University of Cape Town, specializing in oil and gas law. “It essentially opens up a great opportunity for African countries to move in and get deals done quickly.”

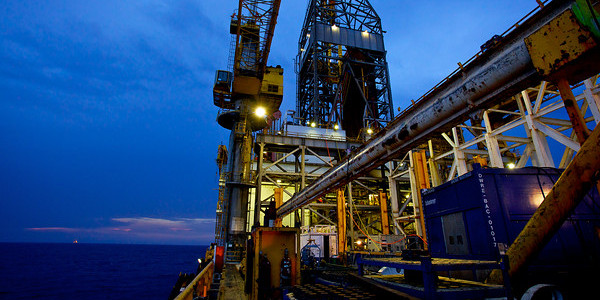

There is a huge amount of capacity on the continent, but top producers lack the infrastructure that can quickly plug the gap. “The largest challenge is financing,” said Linda Mabhena-Olagunju, managing director at DLO Energy Resources Group, an independent power provider in South Africa. There has not been the incentive for foreign capital investments in African hydrocarbon infrastructure amid a global emphasis on developing renewable energy.

In this context, Nigeria, the continent’s biggest oil producer, is pushing for local investors, such as the African Export-Import Bank, to provide alternative funding sources. The country has the largest known gas reserves in Africa. “We want to build a trans-Saharan gas pipeline to take our gas all the way down to Algeria, to Europe,” said Timipre Sylva, Nigeria’s minister for petroleum resources. But he warned, “There is no spare capacity that we can immediately offtake to Europe.”

Plans for the 2,500-mile trans-Saharan gas pipeline, known as NIGAL, were inked in 2009. It aims to run through northern Nigeria, on to Niger and Algeria, and through to Europe. However, construction was only revived last year due to a dispute between Algiers and Niamey.

Algeria, which currently provides about 11 percent of European gas, is perhaps best positioned to see a boon in exports. Despite the closure of a pipeline to Spain over tensions with Morocco, Algeria’s gas exports to Italy jumped 76 percent last year to 21 billion cubic meters, and it has the capacity for another 10 billion cubic meters in exports. Last month, Italy signaled its intention to further increase those imports from Algeria.

The European Union also announced a financial backing of the Eastern Mediterranean pipeline that will connect the region to gas fields in Egypt, but it has run into geopolitical problems with the United States, which pulled out of the project in January citing a decision to no longer back projects that are not green.

Some of Africa’s biggest production sites are in areas with major security challenges. Mozambique holds the third-largest natural gas reserves in Africa. But ongoing armed conflict in the northern province of Cabo Delgado has delayed $50 billion in gas projects. Libyan gas and oil fields are connected by pipelines to Italy but they suffer frequent blockades.

Insurgency has also affected outputs in the Niger Delta. Nigeria depends on refined petroleum imports to meet its own energy needs. “On the one hand, [the U.N. climate change conference] says we are moving away from hydrocarbon fuels, but the reality of today shows that we are going to need oil and gas production more than ever to meet the current demand,” Mabhena-Olagunju said.

The idea that African gas could immediately replace Russian energy is a misconception, experts told Foreign Policy. For example, Nigeria’s OPEC production quota was raised this month to 1.73 million barrels per day from April, but the country has struggled for months to reach assigned oil outputs and said its immediate focus was on meeting the current quota.

“We have spare capacity of about 600,000 barrels at the moment,” Sylva said, “but it needs investment.” Similarly, Toufik Hakkar, the chief executive of Algeria’s state-owned energy firm Sonatrach, suggested that production will focus on growing domestic market demand and current client obligations. Still, in the long term, sanctions against Russia create an opportunity for African leaders to rapidly invest in the infrastructure required to supply significant amounts of African gas to European markets.

Credit | Foreign Policy’s Africa Brief.