By Vincent Duhem

A constellation of Israeli firms, businessmen and consultants with a long-standing foothold in Africa are leveraging their connections to local corridors of power, to indirectly serve the interests of their country. This brand of back-channel diplomacy is thriving – and thoroughly devoid of transparency.

Part 1 of a 4-part series

In early October this year, a military delegation from Sudan made a discreet visit to Israel. Sudanese officials – including Lieutenant-General Mirghani Idris Suleiman, head of the state-run Defense Industries System (DIS) – met with their Israeli counterparts for two days. The visit proved controversial because in Sudan, like in other African countries, the establishment and normalisation of relations with Israel is a hotly contested issue.

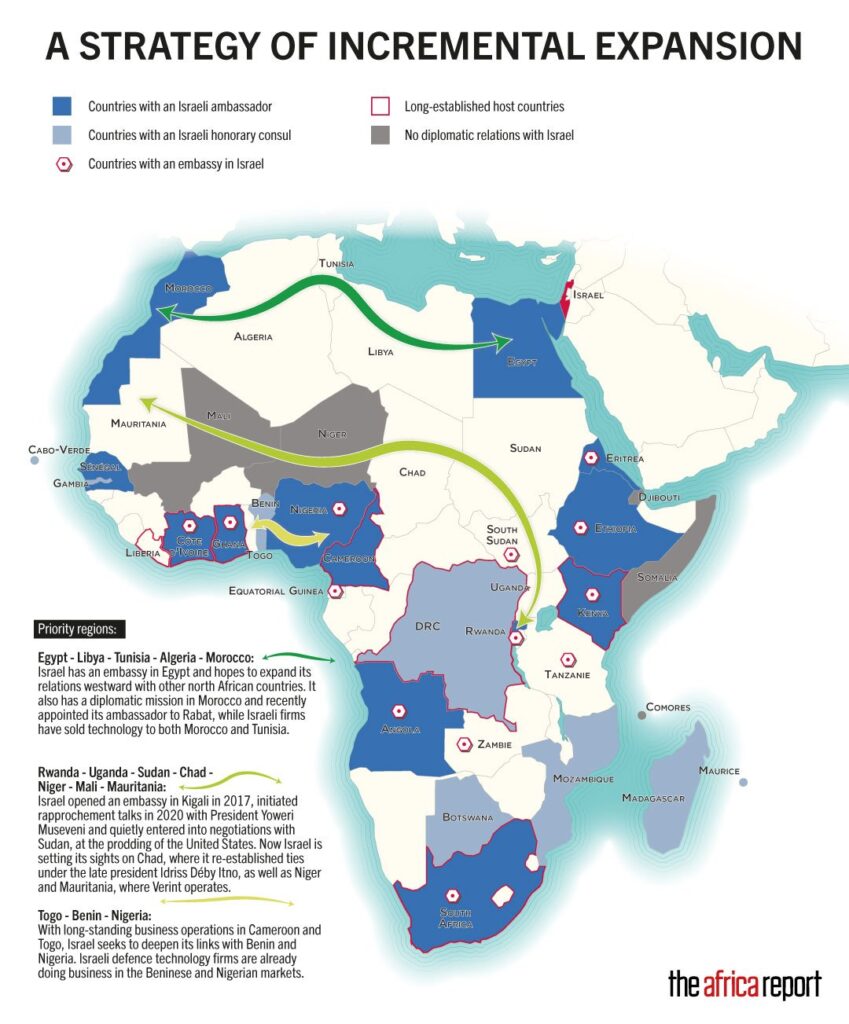

Though the opening of Israel’s first consulate on the continent, in Ghana, which dates back to 1957, the nation’s relations with Africa have especially flourished in the last 10 years, driven by former Prime Minister Benjamin Netanyahu (2009-2020).

His Africa policy oscillated, however, between assertive action and reluctance.

“Although the Israeli leader has undoubtedly achieved some milestones regarding the recognition of his country by almost all African states, he has not yet succeeded to fill these relationships with tangible content. Netanyahu has chosen not to provide his diplomatic corps with sufficient financial resources to further strengthen its involvement in Africa and has thereby failed to deploy his political gains by enhancing his influence on the continent,” Benjamin Augé, an associate research fellow at the French Institute for International Relations (Ifri), said in a November 2020 report.

Dark underside

Lurking beyond surface-level diplomatic relations between states is a somewhat darker underside to Israel’s relationship with Africa – one that stretches from Abidjan to Yaoundé.

Businessmen, a wide array of consultants, and firms with long-established operations on the continent form a system of back-channel diplomacy and its players indirectly serve the interests of their home country. They are Eran Moas, Gaby Peretz, Didier Sabag, Orland Barak, Hubert Haddad, Eran Romano and Igal Cohen.

They have access to African presidents and expertise in areas like intelligence, surveillance, cybersecurity and the arms trade, while acting as a gateway for Israeli companies to expand to Africa.

Some companies and business leaders set up shop in Africa to develop agricultural projects, and then later branched out into the security field because African states approached them for help.

Israeli firms have dominated the wiretapping and electronic surveillance market in sub-Saharan Africa for several years now. The most well-known outfits are Verint and NSO Group, the latter of which was founded by Shalev Hulio and whose star product is the spyware software Pegasus.

Others are Mer Group, which operates in the Democratic Republic of the Congo – providing services to its national intelligence agency – as well as in Guinea, Nigeria and the Republic of Congo, and Elbit Systems, which is present in Angola, Ethiopia, Nigeria and South Africa.

These firms’ main selling point are their close ties with the Israeli army and intelligence services. Many of their employees previously served in the Israel Defence Forces’ cyber-warfare-focused Unit 8200. This is true of Shabtai Shavit, who runs the Mer Group subsidiary Athena GS3 and was the director of Mossad, Israel’s national intelligence agency, from 1989 to 1996.

Shavit is more than well acquainted with Africa, having fostered relations between the intelligence services of Israel, Zaire under Mobutu Sese Seko’s rule and Cameroon. Verint, for its part, is headed by Dan Bodner, a former Israeli army officer.

Approached by African states

“Some companies and business leaders set up shop in Africa to develop agricultural projects, and then later branched out into the security field because African states approached them for help,” a source familiar with the continent’s cybersecurity sector tells The Africa Report.

While these firms have actual ties to Israel’s intelligence services, some don’t hesitate to oversell them. “There are lots of wild ideas about this supposed proximity. Yes, it’s true that most systems developers served in Unit 8200, but apart from that, the Israeli government doesn’t necessarily have a direct connection with them and uses equipment that’s even more up-to-date than what they offer. Sometimes these firms end up treading on Mossad’s toes, but the agency doesn’t rely on them for African intel,” says an Israeli businessman working in the continental space.

In sharp contrast to this strategy, other companies choose to play down their Israeli connection altogether, so as to gain entry to markets in countries whose governments have yet to normalise diplomatic relations with Israel.

Such an approach was adopted by a firm that was in attendance at the Milipol Paris security conference in late October. The company recently supplied Nigeria’s government with a phone-tracking system. Incorporated in Canada and with production in Bangladesh, the firm’s management are nonetheless based in Tel Aviv.[H5] In 2018, the company approached the intelligence services of a certain north African country which cut off contact upon discovering its Israeli origins

Eran Moas, a ‘consultant’ to Cameroon’s special forces

By Mathieu Olivier

The Israeli national’s name might not be mentioned in any official military organisational chart, but everyone in Cameroon knows he’s a key player in an Israeli-trained military unit tasked with protecting the president and his wealthy acolytes. Read on for insight into this ex-Israeli soldier and his sprawling network of contacts.

This is part 2 of a 4-part series

One drink after another is poured behind the bar that runs the length of the restaurant. A cocktail bartender handles the shakers like a pro, drawing patrons’ eyes towards him. A few bottles of stronger stuff await their new owner in a bucket brimming with ice that won’t take long to melt.

On this evening, the city’s nightlife delivers for the VIP, affluent customers of The Famous, the trendiest restaurant and bar in Cameroon’s capital, Yaoundé. It takes the form of the amber hue of whisky and the bubbly flavour of champagne.

In the heart of the upper-class neighbourhood of Bastos, The Famous has become a favourite watering hole among Yaoundé’s wealthy set. Retired footballer Samuel Eto’o was recently spotted partying there alongside FIFA head Gianni Infantino. Singers like Charlotte Dipanda and Lady Ponce have performed there, not to mention the rapper Gims and the late musician Wes Madiko.

Amid the crowd of African and international celebrities, one in particular catches our eye: Eran Moas. The bar’s most frequent clientele easily recognise the face of the adviser to the Rapid Intervention Battalion (Battalion d’intervention rapide – BIR), Cameroon’s special forces unit.

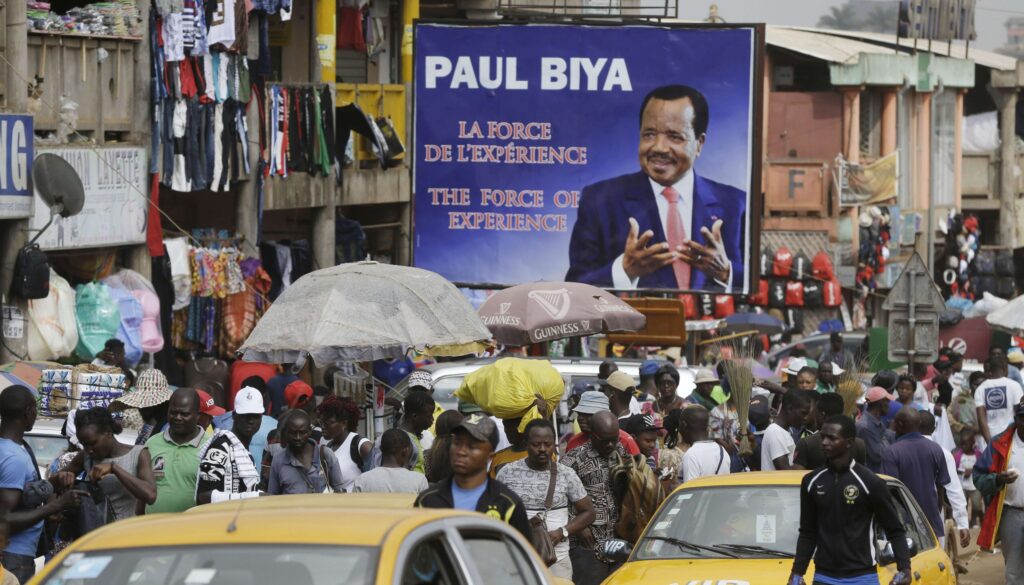

This past 3 November, the Israeli national, who has been living in the central African country for 23 years, celebrated his 45th birthday at The Famous in the company of his closest friends. The festive atmosphere lends a decidedly unguarded air to President Paul Biya’s shadowy elite forces trainer. He feels at home, and with good reason: he is.

Known as ‘the Israeli club’ to members of Yaoundé’s high society, The Famous is run by a company named Danaet. Though its owner isn’t identified in documents provided to the trade and companies register, Moas is one of its main financial backers.

From Kinshasa to Yaoundé

According to several associates, the military adviser manages (or used to manage) stakes, purchased by members of Cameroon’s Israeli community, in a variety of companies, including the communications firms MegaHertz and Ringo, the restaurant Espresso House and the nightlife venue Safari Club, which less than a year ago was renamed Trust Club.

The past sheds some light on how he came to occupy such a central role in Cameroon. Right after completing his mandatory military service in Israel, a then 22-year-old Moas landed in Cameroon in 1998. He worked as a communications technician for Israel-based Tadiran, a leading company in the field of surveillance radar technology. Yaoundé was already on good terms with Tel Aviv at that time.

Following the nearly successful coup against Biya in 1984, the President has placed his trust in the Israelis to reform his security apparatus. He wanted to free himself from French influence, believing France to be too close to his predecessor, Ahmadou Ahidjo. His Zairian neighbour, Mobutu Sese Seko, introduced him to Meir Meyuhas, an Egyptian Jew, who knew Central Africa like the back of his hand.

After working as a secret agent for the Israel Defence Forces (IDF) in the 1950s in Egypt, where his cover was once blown, leading to his arrest and imprisonment, he was moving in Mobutu’s orbit in Kinshasa in the early 1970s. When Zaire severed its relations with Israel after the eruption of the 1973 Arab-Israeli war, Meyuhas was the first person to inform the Israeli ambassador to Egypt, a close confidant of his, of the new development.

In 1982, while he helped train the Zairian leader’s security forces, he was behind the push to re-establish the two countries’ relations, acting as an intermediary between Mobutu and Israel’s prime minister, Ariel Sharon, and defence minister, Shimon Peres.

The Israelis never had to fret about funds drying up: at the express request of President Biya, the BIR was financed through an off-budget account of Cameroon’s national oil company.

Meyuhas jumped at the opportunity to renew his country’s ties with President Biya. Back in Yaoundé, the regular guest at Mont Febe hotel – suite no. 802 became his headquarters – invited a fellow Israeli, Avi Sivan, to join him. Initially appointed as Israel’s defence attaché to Cameroon, Sivan was quickly put in charge of reforming the Presidential Guard, which had until then been trained by the French military.

He lent his share of expertise, being a founding member of one of Israel’s most storied forces, Unit 217. This elite counter-terrorism unit – originally made up of Druze fighters trained to operate in Arab areas – was also called Duvdevan, the Hebrew word for cherry, in honour of its ‘cherry-on-top’ status.

The golden years

Sivan’s training methods drew on Meyuhas’s own strengths. The former secret agent owned several private firms and had – for his prior service – received an exclusive export licence for military equipment from Israel’s ministry of defence.

Reeling from the 1982 Lebanon war, Tel Aviv moved to privatise its defence industry and facilitated the creation of a bevy of arms companies at which former IDF members took on leadership roles.

In other words, it was a great time for anyone looking to get into the security business, especially in Central Africa. Following Sivan’s stint with the Presidential Guard, he threw himself into training Cameroon’s light infantry battalion, which was later rechristened the BIR.

Sivan fully outfitted his troops, providing, among other supplies, uniforms, Galil assault rifles, Negev machine guns and armoured personnel carriers, thanks to his connections to Meyuhas and his son Sami, who joined the family business. The Israelis never had to fret about funds drying up: at the express request of President Biya, the BIR was financed through an off-budget account of Cameroon’s national oil company.

The BIR answered solely to the secretary-general of the presidency. In 1998, when a youthful Moas first arrived in Yaoundé, Sivan was the BIR’s undisputed head, working under Biya’s supervision. Fond of the city’s nightlife, it wasn’t uncommon to see him dancing at a club into the wee morning hours. He also owned a villa in Kribi, where he loved to spend his days fishing.

Though Israel’s defence minister revoked Meyuhas’s exclusive export licence around 2000, business remained lucrative and the BIR continued to be an excellent customer for Israeli companies like Israel Weapon Industries.

The Israeli community’s ranks in Yaoundé had swollen under Sivan’s watch, who was serving as security adviser to the president. In addition to Moas, brigadier generals Meyer Heres and Erez Zuckerman – who resigned from the IDF in 2007 after being involved in a failed operation during the 2006 Lebanon war – joined the BIR as trainers.

In 2010, Sivan died in a helicopter crash under unknown circumstances. Heres and Zuckerman took the reins, but Zuckerman eventually left Cameroon in 2017. Moas worked alongside the pair, becoming adviser to the BIR forces.

Primates and business dealings

Moas picked up French quickly, married a Cameroonian, Lucie, and carved out a life for himself in the heart of Central Africa, in the hills of Yaoundé. Described by a close associate as “an active philanthropist and community member in Cameroon”, he supports NGOs like Ape Action Africa (AAA), which was founded by Sivan in 1996.

In fact, one of his former military comrades, Ofir Drori, is also an ape conservation activist. Whenever Moas meets someone new, he whips out pictures of a chimpanzee that has shared his moniker, Eran, after it was rescued by Mefou Wildlife Sanctuary. He owns at least three villas in Yaoundé and one in Douala, on top of various luxury homes he has bought over the years in the United States, including in Los Angeles.

Though he meets with President Biya several times a year, another Israeli, Brigadier General Baruch Mena, occupies the role of technical adviser to the BIR. According to several sources, Moas is in charge of the business side, such as equipment supply contracts, in addition to the strategic relationship with Ferdinand Ngoh Ngoh, who has been serving as the secretary-general of the presidency since 2011. Both men – and their wives – are on familiar terms.

For years, they have been spending holidays together in Kribi, where Moas still uses Sivan’s old boat, a powerful quad-engine vessel ideal for offshore fishing. What do the decision-makers tied to Biya’s presidency and the Israeli entrepreneur discuss when they are out on the Atlantic?

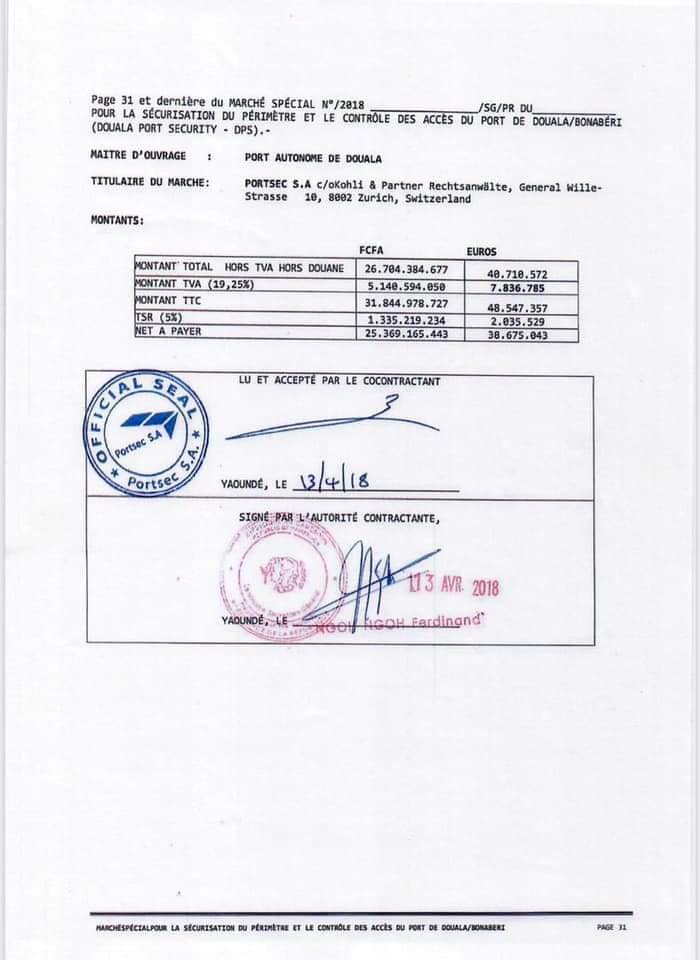

According to documents we have obtained, two companies linked to Moas – PortSec SA (registered in Panama) and Tandyl Development – have records that were signed or drawn up in the past few years by Ngoh Ngoh’s office, including an order of expropriation regarding a real estate project in Yaoundé, and a security agreement – concluded without a tender – involving the Autonomous Port of Douala.

Moas declined to comment when we reached out to him on 6 October. His name missing from the BIR’s organisational chart, he now introduces himself to his less informed interlocutors as a ‘consultant’ and ‘freelance entrepreneur’. It’s quite a half-truth.

Real estate deals and political friends, the underbelly of Israeli Eran Moas’ system

Eran Moas and his Israeli compatriots, big players in the security industry, are investors, thanks to their political connections. In this third part of our series, we delve into a real estate investigation of Yaoundé.

This is part 3 of a 4-part series

It’s midmorning and Philippe Mbarga Mboa is not serene. The minister, who works as a project manager with the presidency of the Republic, exceptionally decides not to go to his office at Etoudi Palace.

Instead, he remains at his home in Yaounde. It is there, in the cozy villa near the national security buildings and the governor of the Centre Region, that he sometimes tackles his most difficult files. The visitor of the day, Ignace Atangana, a teacher by profession, arrives at 10am. A former advisor to the ministry of national education, he is a member of the family – his uncle raised Mboa as his son – and thus, the minister would have preferred to receive him in a warmer setting.

In 2017, Atangana was a dissatisfied man. Representing the Mvog Mbia Tsala and Mvog Ela families, he intended to defend the rights of these founding families of Yaoundé over land located in the centre of the capital, opposite the Palais des Sports. As early as 2011, Roger Semengue, a teacher and businessman, had hoped to build a shopping centre there, approaching the South African ShopRite before turning to the French group CFAO (Carrefour). Plans were drawn up. Visits were made… But the project is no longer progressing.

For years, the state, which does not want to be left out of this large-scale project, has been seemingly doing everything it can to slow down the project, such as not granting the necessary building permits. At the Etoudi Palace, the secretary general of the presidency, Ferdinand Ngoh Ngoh, has taken over the project. As for Atangana, he wrote to the head of state, Paul Biya – with whom, as a privilege of family connections, he has direct contact – to express his discontent. At the beginning of 2017, when he received his interlocutor, Mboa was asked to play the mediator, but the discussions would turn out to be long.

Ferdinand Ngoh Ngoh and discreet expropriation

Atangana is sure of his rights and that of the communities that hold the land permits for the coveted land. When the minister called on him to find an amicable solution with the state, he remained inflexible. Unlike Mboa, he was unaware that the presidency had already made a surreptitious move intended to be decisive.

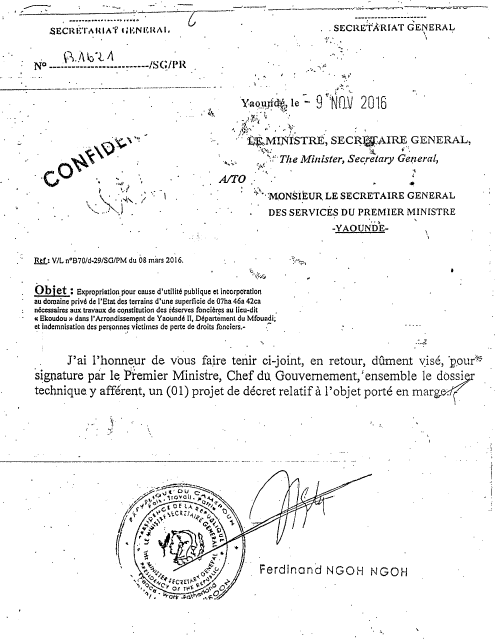

On 9 November 2016, Ngoh sent a letter to the office of Prime Minister Philemon Yang. This letter, classified as confidential, contains a “draft decree” of expropriation “for public utility” applying to a little more than seven hectares of land located opposite the Palais des Sports.

On 14 November, Yang signed the agreement, but his act was not published in the journal officiel (the official journal of the Republic of Cameroon). In return for compensation that the aggrieved communities claim they never received, the state expropriated the Mvog Mbia Tsala and Mvog Ela families.

In complete secrecy. Atangana only learned of the decree several months later, when he was summoned to the ministry of state property. The teacher immediately decided to take legal action to invalidate the act. On 27 November 2020, the administrative court annulled the decree for part of the land titles concerned and will be considering a similar move for the rest of the land in coming months. Nevertheless, the state has not had its last word on the matter.

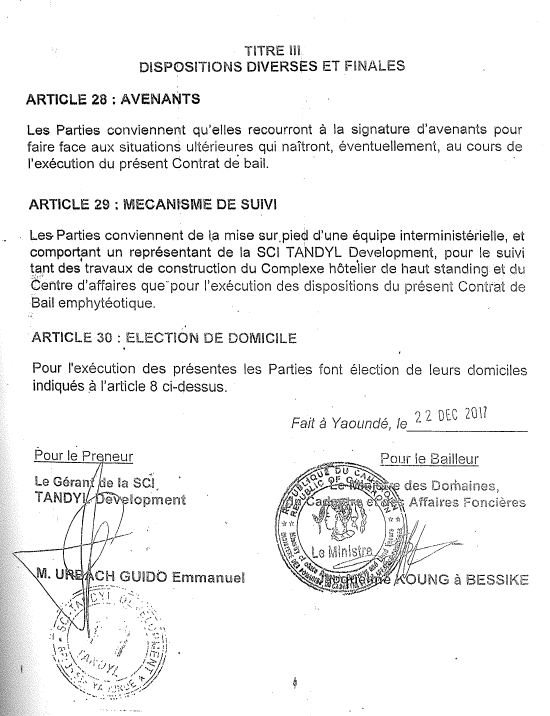

Reserving the right to challenge the court’s decisions before the Supreme Court, the state has remained active since its November 2016 decree. In 2017, it sold the 7 hectares of land to two companies: CFAO and Tandyl Development. The latter was awarded half of the site for 100m CFA francs per year ($171,198), as part of a 99-year long lease signed on 22 December 2017.

In negotiations with the state since the beginning of 2017, the company plans to build a “high standard hotel complex and a business centre” adjacent to the CFAO shopping centre. No doubt due to the legal battle in the administrative court, no work has yet been carried out on the site, and it seems unlikely that a hotel complex will soon be built. If the project did exist, it is now dormant, like Tandyl Development.

From Tandyl Development to Eran Moas

A one-person real estate company with a capital of 500m CFA francs, this company was only included in the Yaoundé trade register 10 months ago. The head office doesn’t look like much: a post office box – number 35.588 – in the Bastos district of the capital. As for its manager, Emmanuel Urbach Guido, he is unknown in Yaounde.

According to information that we were able to collect, it is actually Emanuel Urbach Guido, with only one ‘m’ (contrary to the spelling of the 22 December 2017 lease). The 49-year-old Swiss lawyer, who specialises in contract law and practices in German, English and Hebrew, worked at Kohli & Partners, before adding his name to the Zurich-based law firm in 2018 to form Kohli & Urbach.

Contacted by us on 30 September and 6 October, the former student of Zurich, Jerusalem and New York universities, did not respond. Tandyl Development’s telephone numbers and email addresses were not obtained, but the name Kohli & Partners did not fail to attract our attention. It is not the first time that this firm, specialising in offshore arrangements, has invited itself into Cameroonian circles. Its name appears on a document dated 13 April 2018 and originates from the General Secretariat of the presidency of the Republic – the same institution behind the expropriation decree of November 2016 in Yaoundé.

On this occasion, Ngoh ordered the director general of the Port autonome de Douala (PAD), Cyrus Ngo’o, to sign a contract with the company PortSec SA for the “securing of the perimeter and control of access to the port” for a little more than 25bn CFA francs to 31bn CFA francs after an amendment – over a two year period.

The administrator of this company, registered in Panama – another tax haven – by the Panamanian firm Icaza, Gonzalez, Ruiz & Aleman, is none other than Kohli & Partners, the Zurich firm. Several transfers were executed in October 2018 and January 2019 by the PAD to an account managed by the firm in Liechtenstein.

The Moas system in the sights of Paul Biya’s intelligence

The manager of PortSec SA, Tsafir Tzvi, is unknown to Cameroonians, though he shares a commonality with Kohli & Partners and Tandyl Development: Eran Moas, one of the Israeli advisors to the staff of the Rapid Intervention Battalion (BIR, special forces).

Tsafir Tzvi is a close associate of the latter, who was also behind the creation of Tandyl Development, according to sources who have been in contact with the company. Moreover, Moas, who presents himself as an independent consultant, has already used Kohli & Partners services. In 2016, the firm handled the acquisition of a villa worth 6.5bn CFA francs in Los Angeles, United States, and the name of Eran Moas is associated with other real estate companies in California, such as Crown Royal Developers, which he chaired in the early 2010s.

Is the BIR adviser, who is a favourite interlocutor of Ngoh at the presidency, playing the role of luxury sales agent for his community? Several of our sources clearly indicate this, and the list of Israeli participation in Cameroonian companies, from telecommunications to events management, is long. The Israeli, whom we contacted on 6 October, did not answer our questions about Tandyl Development, though he may have to answer to more ‘persuasive’ authorities.

According to a security source, suspicions of favouritism and corruption have attracted attention at the highest level of the state, with Biya having instructed the national intelligence agency, and their boss, Maxime Eko Eko, to look into the matter.

How Israel made Côte d’Ivoire a promised land

Côte d’Ivoire’s Abidjan, which has been a pillar of Israeli influence in West Africa since president Houphouët-Boigny’s rule, has strengthened its alliance with Tel Aviv and companies under the influence of Stéphane Konan, the late prime minister Hamed Bakayoko’s advisor.

At the beginning of this year, French defence industry specialists were smiling, at least the ones who had left the cold greyness of the Paris region for the warmer temperatures of the Ebrié Lagoon. The Shield Africa trade fair was holding its sixth edition in Abidjan. Launched in 2013, it has become one of Africa’s major events dedicated to defence and security.

Every year, world leaders in the sector and apprentice arms dealers congregate there, amidst soldiers in fatigues. Since 2017, the show has been owned by the Groupement des Industries Françaises de la Défense et de la Sécurité Terrestres et Aéroterrestres, which is responsible for promoting the French defence industry internationally. As a result, its boss, General Patrick Colas des Francs (since replaced by General Charles Baudoin), and the French, feel a bit more at home there. French flagships are the best represented.

However, in January 2019, some men in suits from Thales were pouting. As they entered the main tent, two unusual things caught their attention: the pavilion dedicated to Belarus and the unusually high number of Israeli companies.

Although NSO Group Technologies did not plan on participating until this year, another Israeli heavyweight was already there, namely Verint System, a major specialist in listening and monitoring communication networks. In all, a dozen companies under the banner of the Israeli state were present in the aisles. “It came as a shock to us. We all know that the Israelis are formidable when it comes to the defence technology market,” says a French security specialist.

From Houphouët to Ouattara

Although the French have had a long head start in Côte d’Ivoire, Israel’s envoys have in fact been laying the groundwork for many years. As early as 1962, President Félix Houphouët-Boigny paid a visit to Jerusalem, during which time he grew closer to Prime Minister David Ben Gourion and his foreign affairs minister, Golda Meir, who was the main architect behind the Jewish state’s seduction operation abroad, especially in Africa.

The Ivorian head of state was one of the last African presidents to break diplomatic relations with Israel after the 1973 Yom Kippur War, before re-establishing them in 1985, in the wake of Zaire and Cameroon.

Faced with the September 2002 rebellion and the hostility of France’s President Jacques Chirac, Laurent Gbagbo asked for Israeli military aid. His ministry of defence ended up acquiring advanced transmission equipment and two drones from the Israel.

Tel Aviv even sent 50 military advisers to Abidjan, who were in charge of phone tapping and whom the government housed on the top floor of Hotel Sofitel Ivoire. At the instigation of Benny Omer, Israel’s ambassador to Côte d’Ivoire, Tel Aviv also facilitated the arrival of military intelligence specialists and espionage experts, who were tasked with training Ivorian agents.

Although Gbagbo was pushed out during the 2010-2011 post-election crisis, Abidjan had in fact already become – along with Togo – a hub for Israeli business circles seeking investment opportunities in West Africa. Alassane Ouattara did not change this state of affairs.

In June 2012, he made an official visit to Israel and gradually set up his own networks, with help from his old friend Hubert Haddad’s connections. The head of state and the Franco-Israeli businessman know each other well, as they are neighbours in the town of Mougins, their holiday resort in the south of France.

Of mice and men

The young company, NSO, began to establish itself in the Ivorian economic capital during Ouattara’s first term in office. The company has emerged from anonymity in recent years following revelations about its Pegasus eavesdropping, as well as interception software, and gradually taken up residence in Côte d’Ivoire, where Verint, which is a few years older than it, preceded it. Founded in 2010 by electronic intelligence specialists Niv Carmi, Shalev Hulio and Omri Lavie, NSO has been gradually equipping the Ivorian defence and security services, thus making its advisers the real owners of the state’s interception and surveillance system.

The company, based in Herzliya – Israel’s Silicon Valley, north of Tel Aviv – has not only supplied equipment to the presidency, but also to the ministries of interior and defence. In fact, it has provided them with so many supplies that it has even supplanted French behemoths such as Thales on several occasions. Gaby Peretz – an Israeli military equipment broker who has been present in the sub-region since the 1980s, where he has solid contacts – regularly represents the company in Abidjan.

At the head of AD Consultants, he is active in Côte d’Ivoire, Senegal, Ghana and Gabon, both in listening technologies and in ‘traditional’ armaments. As a matter of fact, he recently sold two patrol boats built by Israel Shipyard and is now proposing to equip them with missiles that were manufactured in Israel by Rafael Advanced Defence Systems.

Given his links with NSO, Peretz could also be one of the reasons behind the ongoing reorganisation taking place within the Ivorian ministry of defence. Verint Systems is also believed to be involved, as is another important network, that of Franco-Israeli (born in Casablanca) Didier Sabag, CEO of the company Sapna Ltd. Sabag has also operated in the CAR, Benin, Guinea-Bissau and Morocco on Herzliya’s behalf.

However, in Abidjan, the latter mostly relied on Franco-Ivorian Stéphane Konan, who was close to the late Prime Minister Hamed Bakayoko and a former cybercrime expert who changed his speciality to the electronic defence business.

Konan, the man from Praïa

The name Konan is well known in African Internet circles. A recognised cybercrime expert and the son of the former minister of the Parti Démocratique de Côte d’Ivoire (PDCI) Lambert Kouassi Konan, he has been a key player in the field of security systems and computer exchanges for a long time.

After Ouattara’s arrival to power, he became Bakayoko’s advisor at the ministry of interior, which the mayor of Abobo occupied in April 2011. The two men appreciated each other and, in the mid-2010s, the technician became one of the minister’s closest collaborators when it came to issues related to communication technology.

When we found out about his double-dealing, that was it. Israel and NSO had already conquered Abidjan and sold their equipment…

Although Bakayoko had not yet moved from the interior ministry to the defence ministry, Konan still managed to build a strong network alongside the head of the Grande Loge de Côte d’Ivoire. He regularly collaborated with French cyber-defence specialists, notably Thales and Ercom, the historical service provider of the Direction Générale de la Sécurité Extérieure (DGSE, French intelligence).

According to a source close to the company, French industrialists in West Africa had even listed him as an occasional commercial agent at the time. However, he had other connections as well. During a stay in Libreville, he got close to the Israelis, who equipped the presidency of the Republic’s listening system (the Silam, which remained under the direction of Frenchman Colonel Boisseau).

According to a security source in Paris, Konan’s French friends were not worried at first. Then, at around 2016, Bakayoko’s adviser began to work with NSO and even some of the Israeli’s partners, such as the Indian Purple.

“When we found out about his double-dealing, that was it. Israel and NSO had already conquered Abidjan and sold their equipment to the Direction de la Surveillance du Territoire, the Direction des Services Extérieurs and the Direction des Renseignements Militaires,” says a French Shield Africa regular. The French felt that the ‘damage’ had been done, as Konan had brought Israeli interests closer to the Freemason networks of Bakayoko and Alain-Richard Donwahi (defence minister from January 2016 to July 2017, before Bakayoko succeeded him).

“We had a hard time [with] it,” says a person close to Thales. “During the 2011 post-election crisis, our special forces allowed the Israeli ambassador in Abidjan to be evacuated [Daniel Saada, who was then posted in Paris until July 2021]. So when we saw the Israelis take the markets, we felt betrayed. It’s also a question of means,” says this same source. Today, big French groups are limited by the Sapin II laws on transparency and corruption, which came into force in June 2017. These laws regulate intermediaries’ networks and issue colossal fines if transgressions are committed. However, the Israelis are not subject to these laws.

Mossad’s shadow

Abidjan’s door is now wide open to Herzliya’s actors. The relationship between the Israelis, Hambak and Donwahi has never been better. As for Konan, he still engages in privileged dialogue with Tel Aviv’s envoys. He is now the head of two companies: Picatrix, in Nigeria, and Competences LDA, which he has been managing since 2012 and which is domiciled in Cape Verde. According to a connoisseur of the Abidjan market, the majority of Israel-related business is conducted through the latter.

Konan regularly holds seminars in Praia, where he brings together his Middle Eastern contacts. “The Israelis are among the main partners of my company Compétences, which has subsidiaries in Côte d’Ivoire, Brazil and Nigeria,” he says. “But I […] feel that technology has no nationality […] so I worked with Thales last year on a project for the ministry of defence. The French are very good in some sectors, less so in others.” Konan enjoyed his time with the Israelis, so much so that he sent his son to study law in 2015 at the Hebrew University of Jerusalem, where he graduated top of his class in 2019.

In June 2021, during the latest Shield Africa trade fair, the cybercrime expert acted as an advisor to Téné Birahima Ouattara, the head of state’s brother and current defence minister. Although he was no longer the show’s curator, as was the case in 2017, he still managed to exert a lot of unquestionable influence on those around him: Israeli contacts, former members of Unit 8200 and the Israeli army’s electronic surveillance unit, which serves as a recruitment pool for NSO and Herzliya companies. Are they the armed arms of Mossad, the Israeli foreign intelligence service?

“It’s a little more complicated than that,” says an expert on the subject. “They have a form of independence and Mossad does not necessarily need them to collect information, but they are tools, especially because their employees are all ex-army.”

“In Abidjan, Israel’s ears are tuned to the Lebanese community,” says a security source. According to our information, Tel Aviv and Yamoussoukro have an unofficial agreement to share information obtained from interception systems that Israel installed and maintains.

Mossad suspects that some of the Lebanese in Côte d’Ivoire are financing Hezbollah, a fierce opponent of the Hebrew state and an ally of Iran and Palestinian Hamas. The restaurant sector – and in particular, the large restaurants in zone 4 within the commune of Marcory – as well as the banana, cocoa and rubber industries, are under surveillance, while the overall security of Abidjan airport is in the hands of Avisecure, a local subsidiary of the Israeli-Canadian group Visual Defence.

“Tel Aviv is afraid of seeing a Hezbollah financial base flourish in West Africa, so they kill two birds with one stone, whether it be in Côte d’Ivoire or Nigeria, for example through business and espionage,” says a businessman in the sector. In May 2009, the US Treasury accused Abdul Menhem Kobeïssi, a senior cleric of the Lebanese community in Abidjan, of being one of Hezbollah’s financiers and expelled him from the country.

Tel Aviv and its allies in Washington still believe that Ghadir, the association he represented, strongly backs Hezbollah. As for the Israeli intelligence services, they still view Côte d’Ivoire as the site of the organisation’s first fundraising activity in Africa. It appears that the Herzliya technicians have a bright future on the banks of the Ebrié Lagoon.

Credits | The Africa Report (October 2021 Edition)

[…] and intelligence industries are making inroads across Africa », Global Sentinel, 5 février 2022, https://globalsentinelng.com/how-israels-defence-and-intelligence-industries-are-making-inroads-acro… [consulté le : 29 août 2022].[30]Efrat Neuman, « Behind Big Bucks in Africa: Lawsuit Sheds […]

[…] and intelligence industries are making inroads across Africa”, Global Sentinel, 5 February 2022, https://globalsentinelng.com/how-israels-defence-and-intelligence-industries-are-making-inroads-acro… [Last visit: 29 August 2022]. [30]Efrat Neuman, “Behind Big Bucks in Africa: Lawsuit Sheds […]

[…] para obtener armas y tecnologías de vigilancia29. Una de las empresas israelíes beneficiarias de esta […]

[…] are making inroads across Africa”, Global Sentinel, 5 de febrero de 2022, https://globalsentinelng.com/how-israels-defence-and-intelligence-industries-are-making-inroads-acro… %5BÚltima visita: 29 de agosto de […]

Amazing work

Amazing work keep up the good work

Amazing work keep up the good work.