Summary: Russia’s invasion of Ukraine has significant economic, geopolitical, and social implications that reach African countries, too. Without swift action to shore up African economies, debt defaults, hunger, and instability could ensue.

By David McNair

Russian President Vladimir Putin’s invasion of Ukraine is a watershed moment that has devastated Ukraine, created a European refugee crisis, and united NATO allies in taking unprecedented steps to counter Russian aggression. For African countries, the conflict’s second-order effects compound a series of existing economic and debt challenges already heightened by the coronavirus pandemic. The IMF and World Bank should respond decisively with an economic package that averts the worst impacts of these crises in Africa.

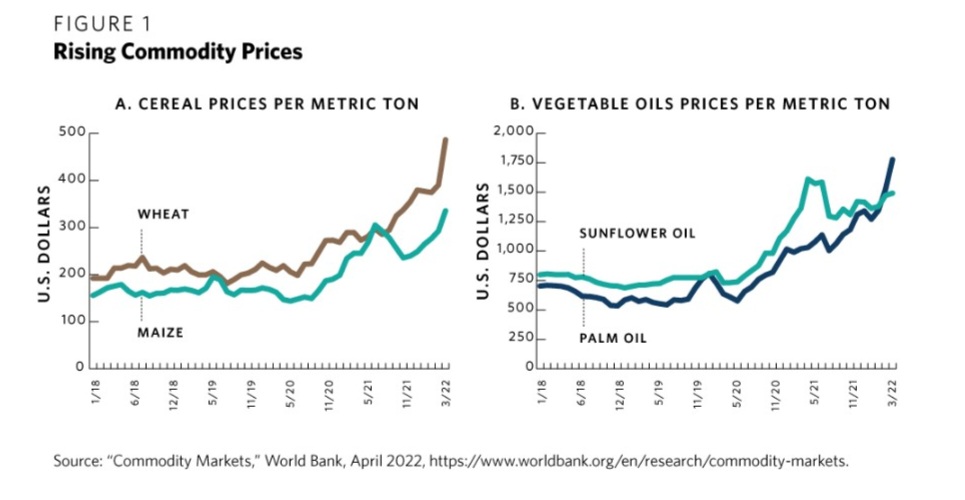

In the wake of the invasion, the prices of staple commodities such as wheat, barley, and vegetable oils have skyrocketed. In March, the UN’s Food Price Index hit record highs. With a monthly increase of 12.6 percent in March from February, food prices are now 33.6 percent higher than they were a year ago (see figure 1). This is, in part, because Russia and Ukraine are the breadbasket of the world, exporting a third of the world’s wheat, a quarter of the world’s barley, and 69 percent of the world’s sunflower oil.

Because the majority of these commodities are exported through Black Sea ports that are now closed, there are 20 million metric tons of wheat and corn in Ukraine that cannot be exported this season. Planting for next year’s harvest has been disrupted by the conflict, with farmers going to the battlefield and those that remain facing fuel and fertilizer shortages. Russia has apparently shelled granaries and even mined farmland.

Russia, which accounts for 18 percent of global potash exports, a critical ingredient in nitrate fertilizer, banned exports before the invasion. Former Russia president Dmitry Medvedev said in March that the country would “supply food and crops only to [its] friends,” because food was its “quiet weapon”—alluding to the fact that Russia may weaponize its export of food commodities.

Energy markets have also seen significant volatility, with oil reaching $130 a barrel in early March before falling again as the United States announced it would release 1 million barrels a day from its strategic reserves to lower prices, as have other oil producers. While rising energy prices could benefit African commodity exporters such as Angola and Nigeria, much of this gain could be offset by the increased costs of importing refined petroleum products. Historical analysis from the IMF suggests that a $5 per barrel increase in oil prices reduced the level of global output by around 0.25 percent, but for African nonexporters that figure increased to 0.6 percent. Furthermore, since the Russian invasion of Ukraine, the UN has cut its global growth forecast by 1 percent, and the IMF’s World Economic Outlook will likely downgrade growth projections.

SUMMER OF DISCONTENT

There are clear parallels with the conditions that led to the Arab Spring protests in 2010–2012, when rising living costs aggravated discontent and catalyzed widespread civil unrest.

The link between food insecurity and stability is well established. In a report on the issue in 2015, the U.S. Intelligence Community assessed that “major food-related interstate conflict (war) is unlikely through 2025, but that lesser forms of conflict and tension—both between groups within countries and between countries—will increase.” The report predicted several changes: those in cities would be first impacted by loss of living standards but small-scale clashes between farmers and pastoralists would arise, too; terrorists and international crime organizations would increase control over food sources to promote their own interests; and disputes over shared marine fisheries and major river basins would rise.

In April 2022, 811 million people had insufficient food intake worldwide. In Africa, this is converging with an acute hunger crisis in West and Central Africa, where the World Food Program (WFP) and the International Fund For Agricultural Development have warned that 41 million people could face a food crisis this year. Prices for basic food staples have jumped 40 percent above the five-year average in Burkina Faso, Liberia, Mali, Mauritania, Niger, Nigeria, Sierra Leone, and Togo. In East Africa, 28.1 million people face acute food insecurity while 7.4 million are experiencing emergency food insecurity, which means “very high acute malnutrition and excess mortality.”

With increasing needs across Africa as well as in Afghanistan, Syria, and Yemen, much of the immediate attention has focused on the direct humanitarian fallout and the need to support organizations such as the WFP, which procures half of its wheat for distribution in humanitarian settings from Ukraine and is simultaneously grappling with increased demand and rising costs to procure food stocks. The organization’s executive director, David Beasley, has warned that the crisis could be “beyond anything we’ve seen since World War II.”

But beyond acute humanitarian situations, rising food prices will have widespread impacts on the livelihoods of African families. The IMF has highlighted that while food’s share of the consumer price index in advanced economies is less than 20 percent, in sub-Saharan Africa it amounts to nearly 40 percent. (The IMF does not breakdown this data for Africa as a continent.)

These challenges add to the ongoing risk of coronavirus variants. A World Health Organization report in April 2022 estimated that by September 2021, 800 million Africans had contracted the virus, yet official data suggests this number is only 11.5 million. July and August 2021 saw a major spike in cases across the continent. As of early April 2022, 84 percent of the continent’s population had not been fully vaccinated.

COMPOUNDING DEBT DISTRESS AND FISCAL PRESSURES

The fallout of the Ukraine crisis, however, is likely to run much deeper because it intersects with weakened economic positions in the wake of the pandemic, preexisting debt challenges, and meager economic support provided by multilateral institutions during the pandemic. The IMF talked of a “great divergence” driven in part by vaccine inequities. But increased costs facing many countries in the wake of Russia’s invasion of Ukraine could dramatically increase the risk of debt distress.

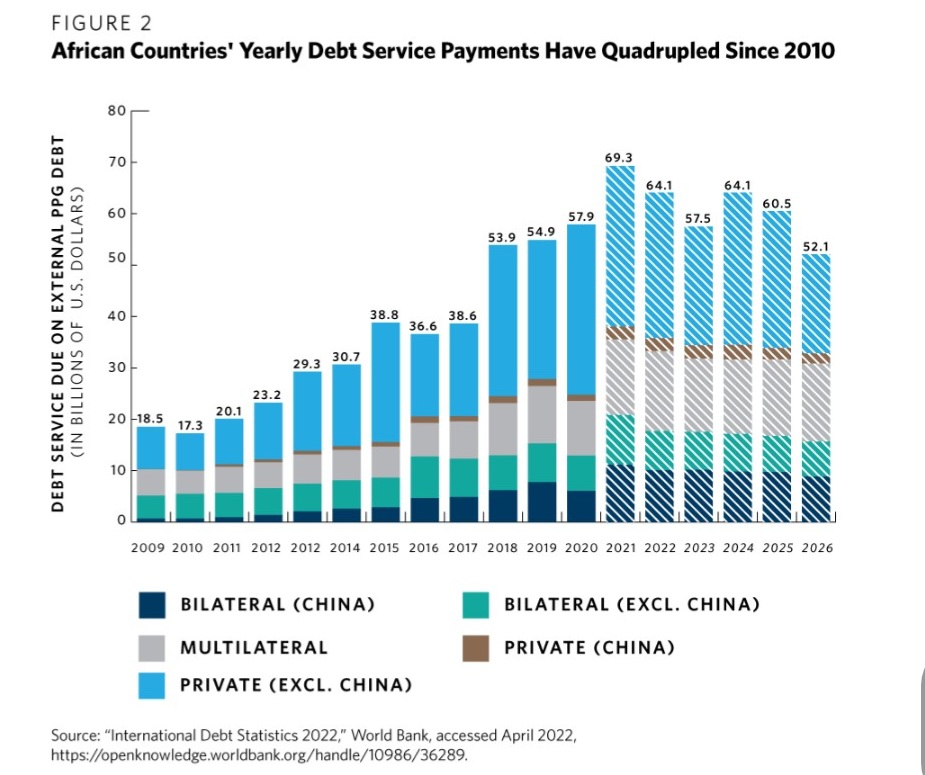

In early April both the IMF and World Bank called for decisive action on debt. Twenty-three African countries are now either bankrupt or at high risk of debt distress. Debt levels in Africa have not been as high as they are today in over a decade. With debt service sucking up increasingly large proportions of budgets and revenues, a wave of defaults in the world’s most vulnerable countries is likely to occur even faster than expected. The debt-to-GDP ratio for low- and middle-income countries increased by 9 percentage points in 2020 (compared to an annual increase of 1.9 percent the decade beforehand).

Of Africa’s external government debt, 57 percent is denominated in U.S. dollars.1 With the U.S. Federal Reserve signaling significant tightening of monetary policy, this is likely to devalue local currency in African countries against the dollar, increasing the costs of servicing existing debt in real terms while potentially increasing the cost of future borrowing. This risks a so-called taper tantrum, where investors exit emerging markets and the cost of borrowing increases.

This is a challenge, not least because the steps taken by the G20 to address debt challenges are failing. The group’s Debt Service Suspension Initiative (DSSI) offered temporary relief from bilateral debt payments during the height of the pandemic, but debt service payments to multilateral institutions and private creditors remained in place. The initiative expired in December 2021.

Its successor, the G20 Common Framework for debt treatments beyond the DSSI, was intended to offer a more comprehensive solution for countries facing debt challenges. But to date only three countries have applied—with good reason. A year and a half into the process, those three countries—Chad, Ethiopia, and Zambia—have been offered no relief. Countries risk being downgraded by credit rating agencies on application to the initiative.

The one area of meaningful economic support from the multilateral system, IMF Special Drawing Rights (SDR), has seen glacial progress. An IMF reserve asset, SDRs are designed to provide liquidity in times of crisis. They can be used to pay debt or can be exchanged for hard currency to support budgetary spending. A general allocation was approved by the IMF board on August 23, 2021.

Due to IMF rules, these SDRs are allocated on the basis of IMF shareholding—so while $440 billion (68 percent) went to G20 countries, only $33 billion (5 percent) went to Africa. As a result the G20 agreed to a $100 billion target to “recycle” SDRs to vulnerable countries. In April 2022, only $36 billion had been pledged. China alone pledged almost a third of this number. None of the pledged SDRs have been disbursed to date.

African countries have a heightened vulnerability to commodity price shocks. For example, Benin and Niger are particularly vulnerable to high food prices, with net food imports adding up to 15 percent and 7 percent of private consumption, respectively. There are particular risks for Africa’s low-income countries: during the 2007–2008 and the 2010–2011 food price shocks, inflation in low-income countries more than doubled.

Inflation was already high in many African countries, in part as a result of pandemic-related supply chain shocks. Ghana’s headline inflation rate in January 2022 was already at 13.9 percent, with food-related inflation at 17.4 percent and with regional rates higher for Accra than rural areas. In Kenya, consumer inflation was 5.39 percent in January 2022.

With the necessary fiscal space, governments could respond with social protection measures to cushion the impact on the most vulnerable. During the pandemic a number of African governments used this to good effect by distributing transfers to households through mobile phones, paychecks, and other means. In 2020, the Senegalese government launched a food distribution program to 1 million vulnerable households.

But all of that requires fiscal space of the kind that is in short supply. In 2020, African finance ministers made the case for a $100 billion stimulus package to help them weather the impacts of the pandemic. Since then, they have watched advanced economies countries offer 18 percent of their GDP in stimulus measures to protect their own economies and to hoard vaccines. African countries are still waiting for that stimulus package, but now the scale of need is much greater and the risks of debt distress and instability are higher.

AN AGENDA FOR THE IMF AND WORLD BANK SPRING MEETINGS

African countries clearly need economic support on a different scale. The stakes could not be clearer in terms of debt sustainability, food insecurity, and political stability.

The World Bank has recognized the scale of the challenge, stepping up with a new, fifteen-month crisis response package of roughly $170 billion to cover April 2022 through June 2023 to help countries deal with the fallout from the war in Ukraine, including food insecurity and lingering aftershocks from the pandemic.

But more needs to be done. Global leaders and finance ministers would therefore do well to respond rapidly with the following actions:

Rapidly provide $100 billion SDR to support pandemic-related response and recovery.

- This should be provided through the IMF Poverty Reduction and Growth Trust and the IMF’s Resilience and Sustainability Trust.

- SDRs should also be channeled through the World Bank and other multilateral development banks.

Provide a comprehensive debt sustainability solution.

- Provide a debt standstill from all creditors upon country application to the Common Framework.

- Explore and provide concrete options to bring private creditors to the table, such as lending-into-arrears policies or domestic legislation.

- Push for publication of eligible debt relief, as estimated by the IMF and World Bank using their Debt Sustainability Framework, to incentivize participation of all creditors and borrowers.

- Set a time line and outline the process for treatment under the Common Framework to promote accountability and quick resolution.

- Support borrower countries to effectively negotiate for their interests.

Instruct multilateral development banks to maximize the use of their balance sheets.

- The World Bank and other multilateral development banks should use their AAA credit rating to borrow more money on capital markets to offer up to $1 trillion in increased lending for vulnerable countries.

NOTES

1 Calculation from ONE, a not-for-profit organization working to end extreme poverty and preventable disease worldwide.

David McNair is a nonresident scholar in the Africa Program and the executive director at ONE.org.

Credit | Carnegie Endowment for International Peace