•Jihadist cells infiltrating as far as Ghana and Ivory Coast, the world’s top cocoa producers, as western counter-terrorism strategy stutters

By Michael M. Phillips

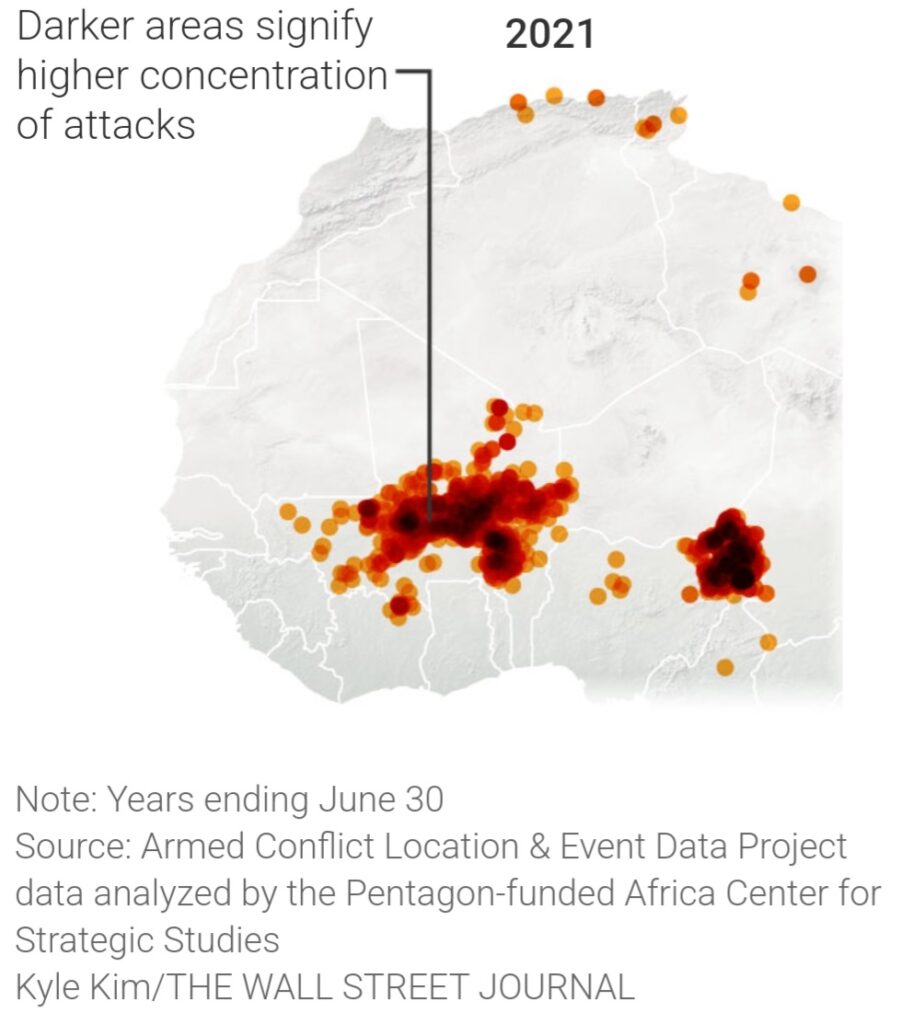

The Islamist militants who have rampaged through the heart of West Africa in recent years are now spreading toward the Gulf of Guinea coast, including some of the continent’s most stable and prosperous countries, according to African and U.S. officials.

The past year has seen an uptick in violence instigated by al Qaeda affiliates along the northern borders of Benin and Togo, with militant cells infiltrating as far as Ghana and Ivory Coast, the world’s top cocoa producers.

The attacks on countries along the bend in Africa’s Atlantic coast appear to confirm warnings that U.S. military commanders have issued for several years: Unless stopped, militant violence won’t remain contained in the landlocked nations of the Sahel, the semiarid expanses directly south of the Sahara.

“It does look like the jihadists have the aim of getting to the sea,” said Ghanaian army Brig. Gen. Felicia Twum-Barima.

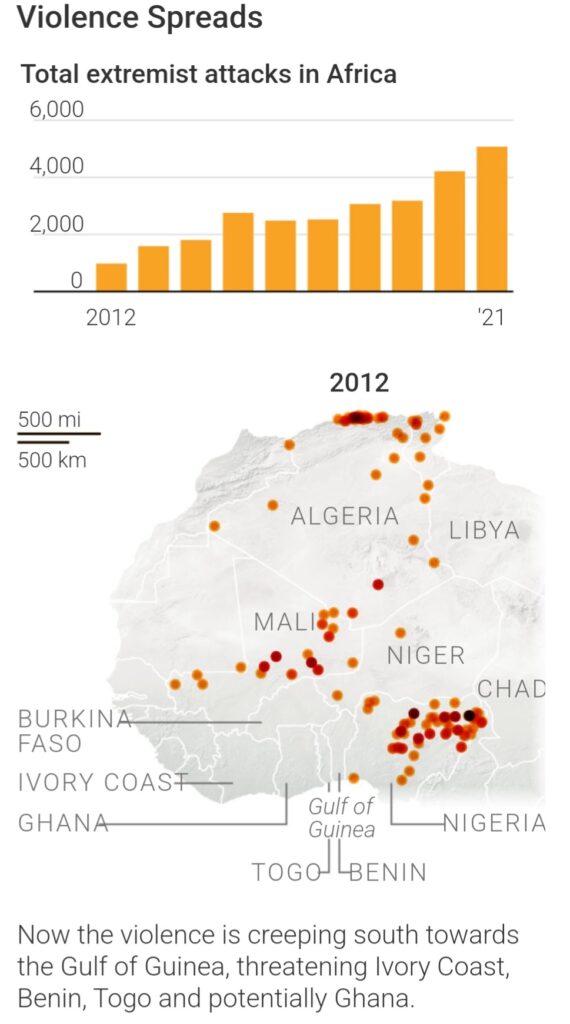

The jihadists’ southward push marks a new chapter in a decadelong security crisis that has claimed thousands of lives since al Qaeda-linked fighters swept through northern Mali in 2012, triggering the deployment of thousands of troops by France to reinforce its former colony. The fighting ebbed, then surged again across the Sahel, with jihadist factions loyal to al Qaeda and Islamic State attacking local and allied forces, as well as each other. Since 2020, the region has seen a wave of coups by soldiers pledging to restore security.

Special-forces soldiers from Ivory Coast at a training base in Jacqueville, Ivory Coast.

France has 4,600 troops fighting in the Sahel, most of them in Mali, but broke with the Malian military junta after it welcomed Russian mercenaries and said it would begin formal negotiations with al Qaeda linked jihadist leaders. In mid February, Paris announced it would withdraw its forces from Mali and redeploy them elsewhere in the region.

“We should be very concerned about the continued expansion of al Qaeda and al Qaeda affiliates across the Sahel, and now threatening to move down into the littoral states,” Rear Adm. Jamie Sands, commander of U.S. special-operations troops in Africa, said in an interview in Ivory Coast last week : “It looks like they’re doing it in a very methodical way.”

Last year, there were 13 Islamist militant attacks in Ivory Coast, five in Benin and one in Togo, according to Armed Conflict Location & Event Data Project figures assembled by the Pentagon-funded Africa Center for Strategic Studies.

By contrast, there were no militant attacks in those countries in 2019, and three in 2020, all in Ivory Coast.

Ghanaian officials say they haven’t seen any incidents inside their country. Attacks, however, have taken place just a few miles away, across the border with Burkina Faso.

On Feb. 8, four park rangers, a French instructor and two drivers were killed and 10 others wounded by a series of booby-trap bombs laid inside the Benin portion of W National Park, according to African Parks, the nonprofit conservation group managing the park.

Two days later, another roadside bomb hit a Benin army commando team, killing one soldier.

A Dutch special-forces soldier coaches Ivory Coast commandos.

France, the former colonial power in Benin and much of the rest of West Africa, retaliated with an airstrike that the French said killed 40 fighters from Ansarul Islam, a small al Qaeda-affiliated outfit.

“I’m not surprised that they’re here—but the speed is alarming,” Gen. Twum-Barima said on the sidelines of the nine-day U.S.-led West African commando exercises in Jacqueville, Ivory Coast that ended Monday.

The annual special-operations training event is intended to help elite West African military units combat militants and counter their guerrilla tactics.

Some 370 troops from four African nations and seven Western countries attended the exercises, hosted for the first time in a country on the Gulf of Guinea. Ghana is slated to host in 2023 and the following year.

The coastal nations aren’t experiencing violence on the scale seen in the hard-hit Sahelian countries. Mali, Niger and Burkina Faso saw 2,005 attacks last year, up 70% from 1,180 in 2020, according to the Africa Center for Strategic Studies. There were 4,839 deaths associated with attacks in the Sahel last year.

But the experience of Burkina Faso is a reminder of how quickly an Islamist insurgency can spread in areas where borders are porous, local grievances festering and government presence limited. The country was relatively quiet in 2017 and, just two years later, found itself overwhelmed by Islamic State and al Qaeda affiliates.

An Ivory Coast commando watches over his comrades during counterterrorism training in mock village, Jacqueville.

Last year, Burkina Faso experienced more than 1,100 attacks.

U.S., Canadian and European efforts to help contain the spread of militancy in the region have been complicated by recent military coups in Mali and Burkina Faso.

In Mali, special-forces Col. Assimi Goïta, a past recipient of U.S. military training, has led two coups since August 2020. Since his second takeover, in May 2021, the military junta has hired 800 to 1,000 mercenaries from a private Russian firm, the Wagner Group, to provide internal security, according to U.S. officials.

The U.S. decried both the coup and the deployment of Russian mercenaries, and didn’t invite Mali to this year’s West African commando exercises.

The U.S. counts on France—which had anchored a 5,400-strong European force focused on Mali until its falling out with the junta—to lead the fight against Islamist militants in the region, with American assistance in intelligence, training, logistics and drone support.

Ivory Coast special forces finish up a morning on the rifle range in Jacqueville.

“Their departure will create a vacuum which will be filled by the terrorist organizations,” Mohamed Bazoum, president of Niger, said after the French announcement. He said that since the coup, Malian soldiers had abandoned posts on Niger’s border.

The U.S. also canceled Burkina Faso’s invitation to the exercises in Ivory Coast following a military coup last month. The Dutch government withdrew its commando trainers.

President Bazoum said French and other European forces would be welcome to set up new bases in Niger and predicted they would also operate in Benin and other coastal countries. France already has thousands of troops stationed across Africa, including 950 in Ivory Coast, 350 in Senegal, 1,450 in Djibouti and 350 in Gabon, an addition to the 4,600 which were spread across the Sahelian battlegrounds of Mali, Niger and Chad.

The U.S. is also discussing ways to boost Ivory Coast’s defensive capabilities, according to American officials.

Governments on the coast now find themselves pinched between the militant threat approaching from the north, and a surge in piracy aimed at commercial shipping in the Gulf of Guinea to their south.

A Ghanaian special-forces soldier checks under a bed during counterterrorism training in Jacqueville.

Militants see economic opportunity in the coastal countries, according to U.S. and African officials. Ghana fears that Islamist groups aim to gain control of the country’s gold mines. U.S. intelligence agencies estimate al Qaeda affiliates already extort about $20 million in cash or gold each year from artisanal miners in the Sahel.

Supporters of Islamic State of the Greater Sahara also operate warehouses in Benin, Ghana and Togo, according to a United Nations report.

Both Islamic State and JNIM, the al Qaeda umbrella group, take advantage of pastoral and smuggling routes in the north of Ghana and Benin, European security officials say.

Commanders and diplomats warn that military action alone is unlikely to stem expansion of extremist violence. African militant groups often take root in isolated areas where governments are weakest, exploiting local grievances and rivalries with the promise of strict enforcement of their interpretation of Islamic law.

—Benoit Faucon in London and Matthew Dalton in Paris contributed to this article.

Michael M. Phillips at michael.phillips@wsj.com. Photographs by Michael M. Phillips/The Wall Street Journal

Credit | WSJ