•An Age-Old Profession Has Changed, Raising Questions About Accountability And Effectiveness

By ADF

In Frederick Forsyth’s 1974 novel, “The Dogs of War,” a band of mercenaries slips into a small, fictional African nation at the direction of a Western tycoon bent on deposing the nation’s dictator to exploit valuable platinum.

The novel, and the 1980 movie based upon it, tells a violent tale that paints a stereotypical picture of mercenaries: cynical, amoral, highly trained, heavily armed, single-minded and beholden to those who pay them.

In Forsyth’s story, the small band of hired guns are veterans of other clandestine battles, operating through shadowy deals, selling their services to questionable benefactors.

The modern mercenary is more likely to operate under a corporate banner, sometimes with government ties, striking deals with legitimate administrations to crush insurgencies and end civil wars.

Mercenaries are about as old as war itself. Persia’s King Xerxes I is said to have employed Greek fighters in 484 B.C. Soldiers for hire have populated many of history’s well-known wars, from the Balearic Islands shepherds who fought for Carthage during the Punic Wars against Rome, to the German auxiliary soldiers known as Hessians who fought for the British in the American Revolution.

Mercenaries also have deep roots in African warfare. Egyptian Pharaoh Ramses II is said to have used more than 10,000 mercenaries in the 13th century B.C. Such fighters also were hallmarks of colonial and Cold War eras.

Maj. Michael “Mad Mike” Hoare, a British Army veteran of World War II, once was considered the world’s best-known mercenary. He fought at the behest of Congolese Prime Minister Moïse Tshombe against the communist-backed Simba rebellion in 1964, according to a February 2020 BBC obituary. His men became known as “The Wild Geese,” and a fictional movie was based on their exploits.

In 1981, Hoare’s career ended in embarrassment when he and 46 of his recruits tried to overthrow the socialist government of President France Albert René in the Seychelles. An airport blunder by one man revealed a disassembled AK-47. In an attempt to escape, the mercenaries commandeered an Air India plane back to South Africa, the BBC reported. A year later, Hoare and his men were tried in the hijacking. Hoare spent 33 months in prison.

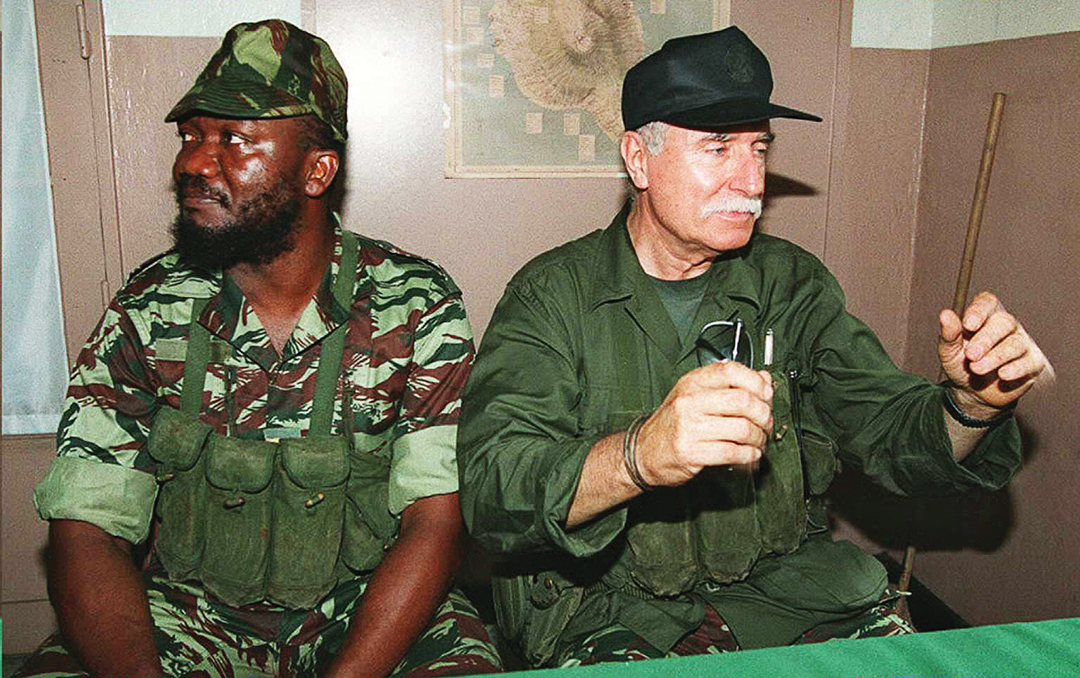

Starting in 1961, well-known French mercenary Bob Denard led uprisings in Angola, the former Belgian Congo, Benin, Zimbabwe (then called Rhodesia) and several times in the Comoros, according to The New York Times. It was in that tiny island nation in October 1995 that French forces stormed the country to reverse his third coup there, marching the limping, gray-haired man out of the barracks outside the capital, Moroni. He died in 2007.

Some more modern incarnations of the “soldier of fortune” are likely to be employed by what are called private military companies (PMCs). These businesses, sometimes formed by veterans of national militaries, can provide anything from logistics and training to lethal force on the battlefield.

They have been a steady presence in Africa for at least a generation, selling their services in high-profile conflicts all over the continent. Their use fuels ongoing debates about accountability. PMCs coming in from outside raise difficult questions about foreign motives and exploitation of African nations and their valuable resources.

TYPES OF ‘MERCENARY’ GROUPS

Mercenary is a term often applied to anyone working in a military or security context outside of a state military or police institution. But there are distinctions that should be noted when looking at those hired to perform functions traditionally reserved for the military.

Here are some useful definitions:

Mercenaries: This term typically applies to individuals who sell their services to fighting forces or causes as freelancers. They take part directly in hostilities, do so for private gain and for sums typically exceeding those paid to combatants in the armed forces, according to international humanitarian law. They are not nationals or residents of territories controlled by parties in the conflict and are not sent by nonparty nations as members of their armed forces.

The 1989 International Convention Against the Recruitment, Use, Financing and Training of Mercenaries forbids the recruitment and use of mercenaries. Thirty-seven nations are parties to the treaty, including 10 African nations: Cameroon, Equatorial Guinea, Guinea, Liberia, Libya, Mali, Mauritania, Senegal, the Seychelles and Togo. Five others — Angola, the Democratic Republic of the Congo, Morocco, Nigeria and the Republic of the Congo — have signed, but not ratified, the treaty.

Auxiliaries: These fighters are organized differently than regular military forces and might consist of troops from foreign or allied nations that serve another nation at war. An example of this would be the Hessians used by the British in the American Revolution.

Also, auxiliaries can include local fighters recruited to serve with colonial troops. For example, French colonial forces used Muslim fighters known as Harkis during the Algerian War of Independence from 1954 to 1962.

Private Military Companies: This is the more modern version of what commonly are called mercenaries. PMCs, sometimes called private military security companies, are legal entities, unlike true mercenaries. However, their use is controversial and often raises questions about accountability and actual or potential abuses. Various countries take differing positions on the use of PMCs.

A PMC is a private business that typically has several characteristics. First, it sells its services to national governments, international groups and other actors. Those services can include guarding convoys, buildings and personnel; maintaining and operating weapons; overseeing detainees; and advising and training local security forces, according to the International Committee of the Red Cross.

Sometimes, these groups engage in “direct, tactical military assistance” to include combat on the front lines of a conflict, according to American scholar and political scientist Peter W. Singer. Sometimes, services include intelligence, logistics and maintenance.

These private groups have been used in conflicts all over the world in places such as Afghanistan, Iraq, Kosovo, Syria and the former Yugoslavia. Such groups recently have been active in Africa in the Central African Republic, Libya and Mozambique, to name a few.

The use of PMCs is complicated from a legal standpoint. Put simply, if PMC employees are not used as combatants, then they are by definition civilians and entitled to all associated protections.

PROMINENT PMCs IN AFRICA

Several PMCs have been involved in high-profile African conflicts over the past 30 or so years. Some of the more prominent ones are profiled below.

Perhaps the most well-known African PMC — and one of the first — was Executive Outcomes (EO), founded in 1989 by Eeben Barlow, a former officer in the South African Defence Force. Barlow’s connections and experience — he was a lieutenant colonel — afforded him access to personnel with a range of military and tactical experience.

That, coupled with equipment that included cargo and troop carriers, light aircraft and surveillance equipment, allowed EO to operate with efficiency and effectiveness in two African conflicts: civil wars in Angola and Sierra Leone, wrote South African journalist Khareen Pech. She reported her findings in the 1999 book “Peace, Profit or Plunder? The Privatisation of Security in War-Torn African Societies,” published by the Institute for Security Studies.

In Angola, EO used Mi-24 helicopter gunships, converted Mi-17 troop-carriers and L-39 trainer jet fighters, Pech wrote. It also operated several light aircraft and two Boeing 727s out of airports in Johannesburg and Malta. Through troop training and other support, EO is credited with helping to turn the tide in favor of government forces during that conflict.

In Sierra Leone, EO was hired in the mid-1990s to help government forces in their fight against Revolutionary United Front rebels. Government forces eventually defeated rebels, secured a peace treaty and held elections.

EO, which frequently has been the subject of controversy, shut down in the late 1990s, but Barlow announced in a December 2020 post to his Facebook page that the company had been reactivated.

Another PMC active on the continent is South Africa-based Dyck Advisory Group (DAG), which was formed by Lionel Dyck, a former colonel in the Zimbabwean military.

DAG offers a range of services, according to its website, which include counterpoaching, explosive hazard management and canine services. Its most recent and high-profile engagement on the continent was its involvement in the growing violent insurgency in northern Mozambique’s Cabo Delgado province. DAG was called in to help Mozambican authorities put down the Islamic State-backed insurgency in 2020, but its one-year contract reportedly was scheduled to end in early April 2021.

DAG had some success during its presence in Mozambique. It came in after extremists had routed the forces of the Russian PMC Wagner Group. However, in a March 2021 report, Amnesty International accused the organization — and other parties to the conflict — of indiscriminate attacks on civilians.

The report accused Dyck Advisory Group staff of opening fire indiscriminately on civilians while pursuing insurgent fighters.

DAG founder Lionel Dyck told Reuters: “We take these allegations very seriously and we are going to put an independent legal team in there shortly to do a board of inquiry and look at what we are doing.”

Russia’s Wagner Group is perhaps the most active and notorious PMC operating on the continent now. It has been active in the Central African Republic, Libya, Madagascar, Mozambique and Sudan. It pulled out of Mozambique after Islamic State-aligned extremists there imposed heavy losses on its personnel.

Wagner Group is a prime example of a private organization being used as a national proxy to secure influence in a foreign nation without having to submit to the scrutiny usually brought on by the use of more official government and military channels.

Wagner is linked to Yevgeny Prigozhin, a Russian businessman and close associate of Russian President Vladimir Putin. The oligarch is said to run the company. In fact, experts say that Russia uses PMCs such as Wagner as a way to advance national foreign policy objectives in other nations without the direct involvement of the Russian government.

BALANCING BENEFITS AND THREATS

The use of PMCs and mercenaries was discussed in February 2019 during the United Nations Security Council debate on “Mercenary activities as a source of insecurity and destabilization in Africa.” Equatorial Guinean President Teodoro Obiang Nguema Mbasogo presided, and members discussed the potential destabilizing aspects of such forces balanced against the supervised use of PMCs to train militaries and offer much-needed logistical support.

Mercenary forces were cited as a threat to African nations, especially in regions with rich natural resources. President Obiang said his nation became a mercenary target after oil was discovered in the 1990s, adding that there had been five attempts to invade Equatorial Guinea using mercenaries. “These mercenaries attempted to assassinate me and my family in December 2017,” he told the Security Council.

Participants spoke of updating legislation on mercenaries, using a legal framework similar to those used to counter piracy and terrorism, and of securing borders. Still others said nations must distinguish between destabilizing mercenary groups and more professional and legitimate groups that provide valuable services.

PMCs are likely to continue as a source of debate in Africa for years to come.

Credits | ADF