By CSIS

DOWNLOAD THE REPORT

There is no way to predict whether Russia will actually take military action against the Ukraine, what kind of actions it will take, and how serious the military results will be at the time of this writing. What is already clear, however, is that the U.S. and the North Atlantic Treaty Organization (NATO) are not prepared for a serious military challenge from Russia. It is equally clear that the U.S. blundered badly under the Trump administration by focusing on burden-sharing rather than developing an effective mix of U.S. forces and a coherent effort to correct the many shortfalls in European forces. Furthermore, it is clear that NATO is not making any serious real-world effort to improve its capabilities.

The U.S. did provide some $2.7 billion in military aid to the Ukraine following the Russian seizure of the Crimea and the Russian military intervention in the Eastern Ukraine in 2014. The U.S. did make some improvements in the forces it deployed to Europe. NATO European states also made limited improvements, and various NATO countries took action to improve the speed with which U.S. and European forces could deploy forward in a crisis.

The Russian buildup has also led the U.S. to respond by accelerating improvements, albeit limited, to its own forces. Several NATO European countries have also rushed aid and deployed small military elements forward.

Nevertheless, it is all too clear from this analysis on the size of current European forces by country as well as from any analysis of the current military balance between NATO and Russia why the U.S. has threatened to use sanctions against Russia as a substitute for military capability. Regardless of how the current crisis develops, NATO will now need to make far more effective efforts to improve its forces, make them interoperable, and deal with the challenges posed by the lack of any real integration and by emerging and disruptive technologies (EDTs).

The Emeritus Chair in Strategy at CSIS has prepared an analysis of these issues and challenges. It is entitled, NATO and the Ukraine: Reshaping NATO to Meet the Russian and Chinese Challenge, and is available for download at https://csis-website-prod.s3.amazonaws.com/s3fs-public/publication/220216_Cordesman_NATO_Ukraine.pdf?cS8vKRNOdoYvg3t_y6QMZMSCpadAo90a

In fairness to NATO as an organization and to the advice coming from many U.S. and allied military experts, they all focus on the need for added military forces, for a new strategy, for more effective and interoperable forces, and for modernization on an interoperable level that can adopt to a wide range of new technologies and tactical concepts.

As the following analysis shows, however, the steps toward these objectives fell far short of creating an effective mix of forces and deterrent capabilities in NATO’s forward areas near Russia. Most European states continued at failing to properly improve and modernize their forces, and they ignored the growing warnings that NATO still faced a Russian challenge.

The U.S. failed to exercise effective leadership in building up NATO’s capabilities after the initial Russian invasion of the eastern Ukraine and seizure of the Crimea. Worse, the U.S. wasted nearly half a decade under the Trump administration by focusing on NATO-wide spending quotas like member country defense spending as percent of GNP and by ignoring the need for effective and fully interoperable national military forces.

In fact, if one looks at individual NATO European country’s orders of battle, at the continued aging of many key categories of weapons, the lack of focus on interoperability and sustainability, and the lack of coordinated efforts at modernization, the overall capability of NATO country forces continued to deteriorate in spite of the emphasis on burden-sharing.

The U.S. failed to lead effectively at the presidential level. It failed to effectively rebuild its forward deployed forces and power projection capabilities. Worse, the Trump administration effectively turned U.S. policy toward NATO into a mathematically absurd form of burden-sharing bullying. It pushed America’s European allies to spend more without addressing their many differences, the very different key deficiencies in most member countries’ forces, and their very different shortfalls in modernization and interoperability.

Today, the crisis in the Ukraine makes it all too clear that the U.S. and NATO need to take a very different approach to creating an effective strategy and to NATO’s force planning and modernization on a country-by-country level. Regardless of how Russia’s present pressure on the Ukraine works out, it is clear that Russia is likely to be hostile as long as President Putin is in power.

Moreover, the risk of Russia cooperating with China in putting strategic pressure on the West (and on the world) is increasingly serious. At least on this point, there is no practical prospect that history will end in some form of beneficent “globalism,” rather there is all too high a prospect of global strategic competition at every level from economic power to the capability to wage thermonuclear warfare.

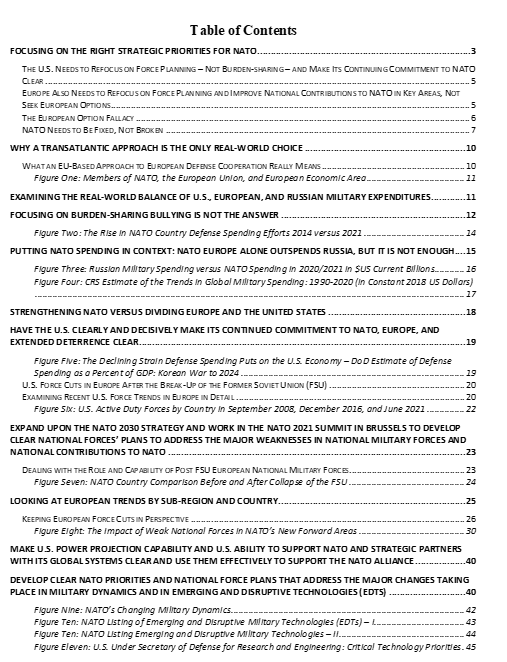

The attached analysis addresses these issues in summary form. It quantifies key trends and problems in existing NATO forces by region and country to the degree that is possible with unclassified data. It highlights the range of new emerging and disruptive technologies (EDTs) that NATO recognizes will be a problem members must now address. It also highlights the need for far more transparency in analyzing NATO’s real-world capabilities and the balance between NATO and Russian forces.

This analysis makes it clear that the U.S. must remain the center of the Atlantic alliance and that any rebalancing of U.S. forces to Asia must take this into account. It makes it clear that most European powers have left important gaps in their military efforts, and they have not created effective plans to modernize and strengthen their contributions to the NATO alliance. It also makes it clear that there is no European alternative to safely deterring Russia and to meeting its military threats that can significantly reduce European dependence on the U.S. – and there are no meaningful ways the European Union can substitute for NATO.

Focusing on the Right Strategic Priorities for NATO

If the Ukraine crisis ends in anything other than a major conflict, the U.S. and its NATO allies must now take a far more serious look at how they are shaping the future defense of Europe, the Atlantic, and the Mediterranean if NATO is to hold together; create an effective structure of deterrence and defense; and ensure that the West, other democracies, and other major powers can compete with both Russia and China. In doing so, the U.S. and all of its strategic partners in NATO must focus on correcting the major shortfalls in the military and deterrent capabilities of each member state, instead of fixating on NATO-wide concepts or common funding efforts.

This is not simply a matter of setting broad priorities and issuing new strategies. Military reality is not an exercise in writing more vague generic statements of good intentions. The Russian threat to the Ukraine has made it all too clear that the U.S. and its allies must create and actually implement meaningful force plans instead of issuing more strategic rhetoric.

NATO must work together to assess the role each country should play in creating a more effective alliance rather than referring to NATO-wide generalities. Member countries must develop credible force plans, programs, and priorities that reflect the radically different capabilities of given NATO countries, and they must find solutions to their radically different funding needs and capabilities by developing a suitable mix of very different national defense budgets.

In doing so, the U.S. must fully recognize its own blunders in focusing on burden-sharing. The U.S. needs to fully consult with its NATO and other strategic partners. The U.S. needs to make it clear that there is no case for some “European” solution to Western security, and it must avoid any future cases like the casual way in which the U.S. engaged Australia and the UK in a closer alliance by suddenly substituting U.S. nuclear submarines for French conventional submarines. As is the case in the Middle East and the rest of the world, the U.S. cannot afford to constantly raise new series of doubts about the ability to rely on the U.S. as a strategic partner.

The U.S. also needs to revitalize its focus on NATO and Europe. China’s emergence as a major strategic challenge is all too real, but Europe and Russia are just as critical to an effective U.S. strategic posture as are China and Asia. The recent U.S. focus on the Chinese threat is all too necessary, but so is the U.S. focus on NATO, Russia, and the rest of the world. The U.S. must treat all its strategic partners as real partners, and the U.S. needs to recognize that its strategic force plans must continue to be global – not swing from region to region.

At the same time, Europe needs to be far more realistic about its strategic dependence on U.S. forces and the major shortfall in most European forces. European members of NATO need to do far more to improve the modernization, interoperability, sustainability, and deployment capabilities of many of its member states. They need to recognize there is no credible European alternative to NATO and an Atlantic alliance, and they should focus on nation-by-nation force improvements, rather than burden-sharing and arbitrary spending levels.

As the following summary analysis of current national forces shows, NATO not only must deal with many individual sets of national military weaknesses, it must address a wide range of “emerging and disruptive” technologies that are steadily reshaping military forces, tactics, and capabilities.1

Once again, it must be stressed that this cannot be done by announcing new NATO strategies in broad terms or setting common goals for the entire alliance. It also cannot be done by repeatedly issuing equally vacuous national defense white papers that do not commit countries to specific actions, plan, programs, and budgets or that do not honestly address the problems in current national forces.

Both the U.S. and European nations need to properly assess national defense spending levels in terms of actual country’s individual military requirements and spending capability. NATO-wide quotes are pointless. At the same time, such efforts need to be driven by net assessments of the relative size of Russian and Belarusian military forces, modernization, and spending, and they need to end the present emphasis on burden-sharing by arbitrary percentage of GDP and equipment spending.

The following data on Russian, U.S., and NATO European military spending alone make it clear that the U.S., all other member countries, and NATO as an organization need to use such net assessments of their present and future capability to deter and defend against Russia, determine what actions member countries should actually do to improve their forces, and set individual national goals for given forces on modernization at a time when there is an ongoing revolution in military affairs that will last for at least the next few decades. They also need to plan collectively to deal with the ongoing emergence of China as a far larger and more effective military superpower than Russia – and in doing so, create a stable balance of deterrence in dealing with both Russia and China.

THE U.S. NEEDS TO REFOCUS ON FORCE PLANNING – NOT BURDEN-SHARING – AND MAKE ITS CONTINUING COMMITMENT TO NATO CLEAR

These changes can only actually occur if the U.S. fully recognizes its own failures to lead effectively and if it revitalizes its approach to the NATO alliance. The Biden administration has already refocused U.S. strategy on some of these goals, rejected the burden-sharing bullying of the Trump administration, and shifted back toward the bipartisan focus on U.S. strategic needs that shaped the policies of both Republican and Democratic administrations since the end of World War II.

At the same time, the Biden administration has not yet defined any detailed approach to shaping an effective U.S. force posture for the future or a strategy that goes beyond generalities and describes clear plans, programs, and budgets for America’s future capabilities in supporting NATO. Europeans still have reason to be concerned about America’s failures.

The U.S. defeat in Afghanistan in August 2021 and the growing U.S. emphasis on the rising threat from China have raised legitimate European concerns over the reliance on the United States. President Macron may be one of the only senior leaders openly calling for a much stronger and EU-based approach to European defense, but in fairness every political leader in Europe still has reasons to be concerned.

For more than a decade there have been series of reports that the U.S. is rebalancing its forces to Asia in ways that reduce its presence outside of Asia and that it is retreating from its strategic commitments to Europe and the Middle East, although such reports have not described real-world trends in U.S. deployments and capabilities that alter the U.S. commitment to NATO.

This became all too clear in February 2022, in the midst of the Ukraine Crisis. The Biden administration issued a new Indo-Pacific strategy at the White House level that was just as vacuous in terms of details as every similar document since the Obama administration, and – with a somewhat astounding lack of any perception of the irony involved – it issued a declassified summary of an equally vacuous top secret strategy document in what seems to have been an effort to show the Biden document should have bipartisan support.2

More substantively, President Trump’s emphasis on “burden-sharing,” and on raising European military spending, came close to strategic bullying. So did his threat to cut U.S. forces in Germany, his failures to confront Russia, and his focus on China. Although the U.S. actually increased some aspects of its commitments to NATO during his administration, his words and actions did undermine European confidence in the United States.

EUROPE ALSO NEEDS TO REFOCUS ON FORCE PLANNING AND IMPROVE NATIONAL CONTRIBUTIONS TO NATO IN KEY AREAS, NOT SEEK EUROPEAN OPTIONS

At the same time, the U.S. has also maintained good reason to be concerned about the defense efforts of most European powers, and there is a need for the U.S. to pressure given NATO European states to increase the key aspects of their defense efforts that really matter. As the country-by-country analysis later in this report also shows, many European states have fallen short in maintaining and modernizing their military forces in spite of Russia’s hardening position and the signals sent by the Russian seizure of the Crimea and the invasion of the Eastern Ukraine.

A majority of the current European members of NATO have been slow – and often faltering – in adapting to the changes in NATO since the fall of the former Soviet Union (FSU) and in reacting to the rise of a more aggressive and threatening Russia – and this is true of many European states that did increase their defense spending and that met NATO’s burden-sharing quotas.

The following review of region-by-region and country-by country European forces as well as their capabilities to deter and defend shows all too clearly how ridiculous the positive rhetoric that has praised higher spending percentages actually appears. This is particularly true in the case of the former Warsaw Pact states, although it is broadly true that pressures to increase percentages of spending did not lead to meaningful improvements in the military capabilities of most European states.

For all of the recent U.S. emphasis on burden-sharing and its claims about the resulting rises in defense spending as a percent of GDP, the following summary analysis of individual country’s military efforts shows how little progress has actually taken place. Moreover, a more detailed review of the force structures and defense plans of individual member countries that examined the largely classified data on their individual shortfalls in interoperability and standardization, progress in joint all domain warfare capability, and their response to emerging and disruptive technologies (EDTs) would show that the overall level of European cooperation in creating effective deterrent and defense capabilities has continued to decline relative to Russia since its initial invasion of the Ukraine in 2014.

THE EUROPEAN OPTION FALLACY

Moreover, the same data make it brutally clear that calls for some form of European defense autonomy linked to the European Union (EU) that have been issued by leaders, such as President Emmanuel Macron of France, are just as absurd as Trump’s emphasis on burden-sharing bullying. Macron stated in a news conference with then German Chancellor Merkel in June 2021 that, “We have succeeded in instilling the idea that European defense, and strategic defense autonomy, can be an alternative project to the trans-Atlantic organization, but very much a solid component of this.”3

President Macron has since raised the same theme on several occasions and repeatedly called for “strategic autonomy.” U.S. and French military relations also deteriorated sharply in September 2021 because of Australia’s decision to buy eight nuclear submarines from the U.S. instead of 12 French conventional ones without consulting France – a decision that highlighted the problems in U.S. efforts to “rebalance to Asia” where the U.S. does not fully inform and consult with its European allies and where other tensions have existed over France’s (Macron’s) efforts to create a “third way” to deal with an emerging Chinese superpower.

At the same time, when it comes to the substance of the issue, the new strategic partnership between the U.S., Australia, and Britain illustrates the fact that cooperation between the U.S. and Europe can play a critical role in strengthening the West’s ability to compete with China. For all of the tensions involved, an actual Australian purchase of nuclear submarines would also give Australia a better and more lasting capability to deter China in the Pacific waters near China than France’s troubled conventional submarine program.

President Macron’s failure to obtain any real gains from his own dialogue with President Putin over the Ukraine is another case in point. France’s effort would have been pointless if the U.S. had not taken the lead in pressuring Russia. Moreover, President Macron’s efforts to actively promote a “third way” in the Pacific that emphasizes trade and cooperation with China seems to be decoupled from the realities of dealing with an emerging authoritarian Chinese superpower that later sections of this report show is becoming an all too real and growing threat. (Although the U.S. failure to join the trade pact that it created in Asia to check China is scarcely a better example.)

At the same time, it is important to note that other European leaders have shown the continued benefits of Transatlantic cooperation. This was true even in the case of Germany. Since 1990, Germany has remained the most uncertain major European power and has become the equivalent of the new “sick man” of Europe in failing to properly maintain and modernize some of the most critical military forces in NATO.

Even so, former Chancellor Merkel emphasized NATO over a “European solution” at the same press conference with Macron, stating that she was glad that President Biden had shifted away from President Trump’s focus on burden-sharing and on reducing the U.S. commitment to Europe, and that instead President Biden was rebuilding a “climate of cooperation.” She noted that, 4

It is very clear from the G7 and NATO talks that the United States sees itself as both a Pacific and an Atlantic nation and, given the strength of China, is naturally challenged to be much stronger in the Pacific than perhaps it was 20 years ago… And that means for us Europeans that we have to take on certain tasks and responsibilities for ourselves… but I see the absolute necessity—and I think this is also expected of the United States of America—that we act coherently.

NATO NEEDS TO BE FIXED, NOT BROKEN

Put simply, the U.S. needs to recognize that NATO needs to be fixed – rather than broken – and Europe needs to recognize that there are no real European alternatives to Atlantic deterrence and defense. It shows that the U.S. and each of its NATO European allies need to focus on making the alliance more effective. They need to cooperate far more in shaping NATO’s real-world strategy and on actual levels of meaningful modernization and cooperation. Moreover, they need to focus on nation-by-nation improvements in the common capability to deter, defend, and cooperate, rather than on burden-sharing, setting arbitrary spending goals, and substituting good intentions for action.

NATO needs new realities, not more rhetoric. Every nation in the alliance needs to do more to actually implement the strategic and force modernization goals set out in NATO’s 2030 plan and to deal with what NATO calls “emerging and disruptive technologies.”5 The plan shows that the creation of a well-balanced, integrated, and interoperable mix of national forces for NATO should be a common U.S., European, and Canadian objective.

At the same time, the summary analysis of individual member country’s forces in this analysis shows that such efforts need to address the military strengths and weaknesses of each member state in very different ways. The NATO alliance needs a far more nuanced country-by-country approach to force planning based on a real net assessment, plans, and budgets. Moreover, the conclusion to this analysis shows that NATO needs to actively review the changing capabilities of the world’s three superpowers and to consult on the rising threat from China, rather than just focusing on Russia, terrorism, and the out of area threats near Europe.

Anthony H. Cordesman holds the Emeritus Chair in Strategy at the Center for Strategic and International Studies in Washington, D.C. He has served as a consultant on Afghanistan to the United States Department of Defense and the United States Department of State.

Please consult the PDF for references: Download the Full Report

WRITTEN BY

Anthony H. CordesmanEmeritus Chair in Strategy

Grace HwangProgram Coordinator and Research Assistant, Burke Chair in Strategy and Transnational Threats Project

Credit | CSIS