By Alexander Onukwue

Nigeria’s dependence on foreign imports to satisfy growing wheat consumption might face its biggest challenge yet due to Russia’s war with Ukraine.

Bread, pasta, noodles, and semolina are among the most threatened food items made from wheat flour in the country. At least three of these increased in price by 50% or more between late 2020 and January 2022, with supply pressures set to induce further increases this month.

“We are expecting between a 10 and 15% increase in the price of flour and flour-based products,” says Deepankar Rustagi, the CEO of Omnibiz, a startup that uses web apps to help retailers order groceries from manufacturers.

Russia supplies a lot of Nigeria’s wheat

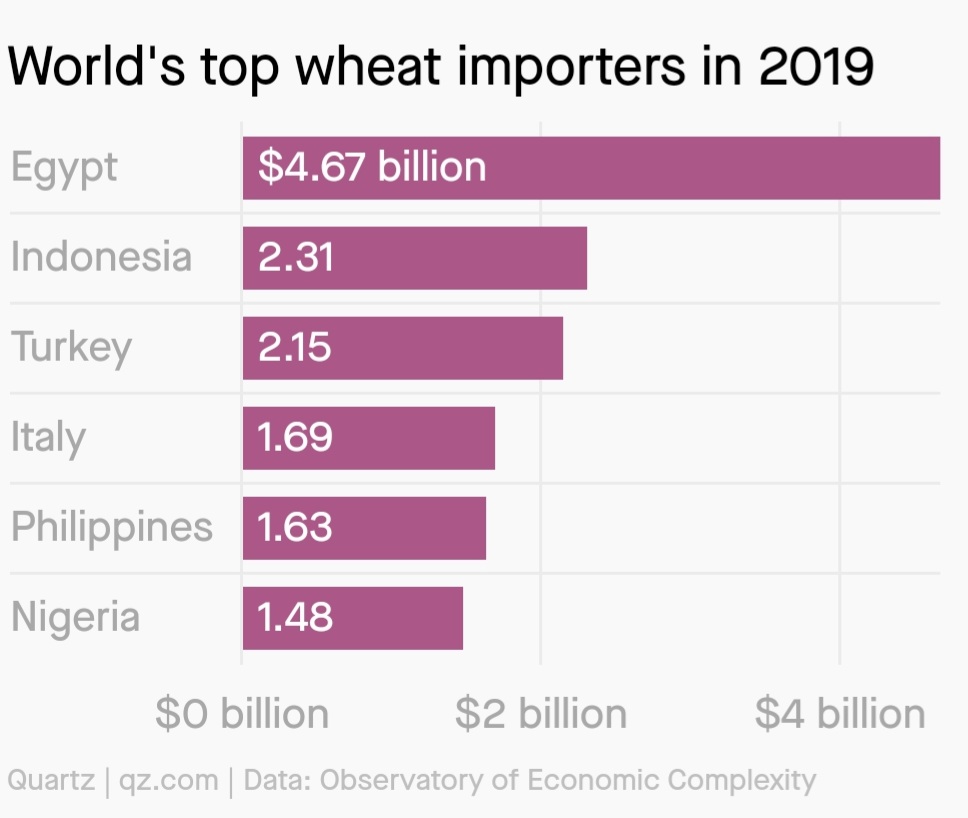

Nigeria’s import of $1.48 billion worth of wheat in 2019 made it the world’s 6th largest importer of the cereal grain that year, according to the Observatory of Economic Complexity, an aggregator of economic and trade data.

The top two sources of that wheat were the US, and Russia. Wheat was Nigeria’s third most imported product in 2019, according to the OEC.

The European Union became the leading exporter of wheat to Nigeria in 2020, as flour millers looked to countries like Latvia and Lithuania for cheaper wheat. Still, Russia supplied 17% (pdf) of the wheat that transforms to bread on Nigerian breakfast tables, per the US Department of Agriculture (USDA), citing industry data.

As the specter of the Russia-Ukraine war rose in February, analysts began warning of the potential adverse impact on food prices and political stability in North Africa, where expensive food has ignited a revolution before. The level of alarm has not quite been the same in Nigeria as the war raises oil prices which has politicians making promises ahead of next year’s presidential elections.

Nigerian bread was already becoming more expensive before the Russia-Ukraine war

But international wheat prices have hit record highs this week, which could invite tougher questions on worsening food insecurity in Africa’s largest economy where more than half of household expenses is on food alone, and nearly 9 million people are food insecure, thanks in part to militant insurgency in the northern states.

Local production needs to step up

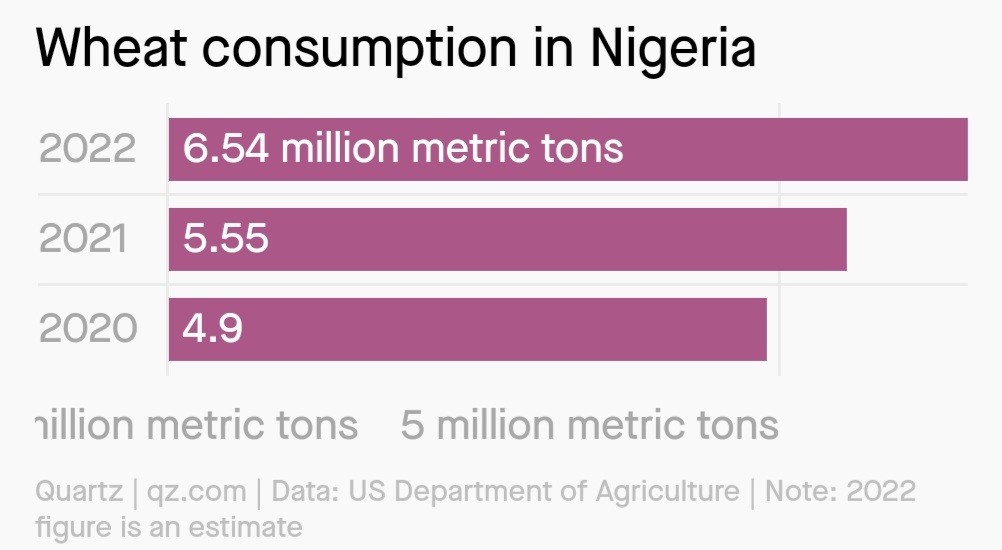

Nigeria’s wheat demand could reach 6.5 million metric tons this year, 13% more than 2021, the USDA says.

Filling that demand is a problem for at least two reasons: foreign exchange scarcity that leads flour millers to buy dollars at 20% higher than the central bank’s rate, and increasing cost of freight for imports.about:blank

But even if these were fixed in the short term, Rustagi, the Omnibiz chief executive, thinks Nigeria has to become more self-sufficient on wheat production to limit the impact of events like the current war. A combination of poor farming practices and lack of improved seeds restricts national average yield to 1.1 metric ton per hectare, but the broader irony of Nigeria’s food insecurity is that most of the country’s wheat is produced in those northern states besieged by terrorism.

Credit | Quartz Africa