•Beijing was once wary of the region. Now, it’s all-in.

By Anchal Vohra

Last month, China hosted foreign ministers of several Persian Gulf countries to hash out ways to upgrade ties and deepen security cooperation. A few days later, Iran’s foreign minister arrived in Beijing to discuss a $400 billion investment and security agreement to mitigate the impact of U.S. sanctions on Iran’s economy. Another report confirmed that Beijing has been helping Saudis build a new batch of ballistic missiles that Riyadh has likely commissioned to counter Iran’s missile fleet.

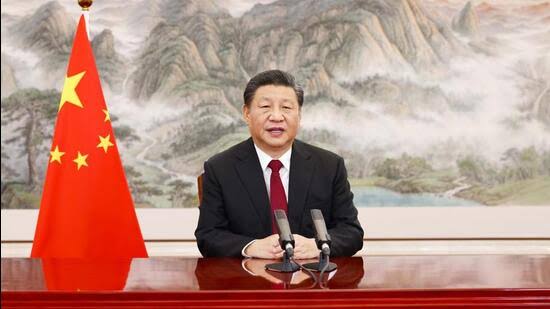

China presented this flurry of visits and announcements as an example of its equal distance policy toward the respective regional players. But it is also an expression of how Chinese policy toward the Middle East has dramatically changed under Chinese President Xi Jinping.

Traditionally, Beijing had been wary of getting embroiled in a region that a Chinese scholar once described as a “chaotic and dangerous graveyard burying empires.” But in 2014, Xi vowed to more than double trade with the region by 2023. China has become the biggest importer of crude, with almost half of it coming from the Middle East, and emerged as the region’s largest trading partner over the last few years.

China has slowly but steadily expanded its security footprint even though it insists on coming across as a development partner in the crisis-ridden region. In mid-January, Beijing unleashed its soft power when it announced the construction of thousands of schools, health care centers, and homes destroyed in Iraq’s successive conflicts. According to Iraqi officials, Iraq needs a total of 8,000 schools to “fill the gap in the education sector.” China has decided to construct the bulk of those—7,000 schools—to help educate millions of children. It will also build nearly 90,000 houses in Sadr City, the bastion of Iraq’s strongest political leader and cleric, Muqtada al-Sadr; improve Baghdad’s sewerage; build an airport in Nasiriyah, Iraq; and construct 1,000 health care clinics all over the country—all to pay for Iraqi oil.

It’s true that China needs oil for its growing markets and large population, and it’s reasonable that China wants to secure the maritime supply routes it fears an adversarial United States can block if it decided to do so. It is also well known that Beijing wishes to expand its business interests in the Middle East through the Belt and Road Initiative, Xi’s pet project envisaged to make China the driver of future globalization. The Middle East lies at the crossroads between Asia, Africa, and Europe and is crucial to China’s economic expansion. But these seemingly innocuous and business-oriented objectives are part of a bigger strategy.

The final aim is to establish China as a world power—its rightful place, according to Xi. China intends to upend the United States’ predominance in the Middle East and carve it out as an area under Beijing’s influence, not just to secure its energy needs or grow its businesses but also to advertise its political ideology.

On the face of it, Beijing claims to be taking the region on a path to economic recovery and is building infrastructure in exchange for oil and gas. In reality, it has extended its diplomatic outreach and marched forth on a much more insidious project—backing regional dictators and authoritarians to grant them credibility and, in turn, seeking legitimacy for its own one-party authoritative regime.

China wants to show the Chinese people that its political ideology has been better all along and seek appreciation at the global level that its thinking—economic growth before democracy or, rather, at the cost of democracy—is the path to ceasing conflict even in the most volatile region and improving quality of life.

Sun Degang, a Middle East affairs specialist at Fudan University, wrote that China proffered developmental peace over the Western concept of democratic peace in the Middle East. He added Beijing believed that the international community should focus on providing much-needed economic assistance to the region “instead of exporting ill-fitting democracy.”

But at the heart of this policy is Xi’s belief that China—not the United States—should be the world’s superpower. China’s dogged challenge to the United States’ position is strategized to win the hearts and minds of the Chinese first, who have repeatedly been told by China’s Communist Party that their rise in the global hierarchy is being slowed by Western imperialists.

Shaojin Chai, a political scientist at the University of Sharjah, told Foreign Policy that China is confident that its development approach is more popular than the West’s diplomacy of “values and democratic peace” in the Middle East. “Based on Chinese political philosophy and the mentality of the ruling elites, only development and economic prosperity can bring peace, civilization, and good governance,” he said.

Decades of war, bloodshed, and failed U.S. policies in the Middle East—as well as U.S. President Joe Biden’s retreat from the region—have made China’s narrative appealing to many Arabs. The monarchs, dictators, and clerics seem not to mind the abuse of Uyghur Muslims in Xinjiang, China, and have even backed China’s so-called deradicalization efforts at Uyghur internment or “reeducation” camps. Although the Arab people may not be fully aware of the details of the diplomatic handshake between their authoritative rulers and Chinese leadership, those who have suffered war and deprivation of basic necessities for far too long are receptive to China’s political ideas if they can bring about economic well-being.

“I think many assume [the Middle East and North Africa] is just flirting with China, that they’ll eventually realize that the West is their natural partner, but that assumption seems wrong to me,” said Jonathan Fulton, assistant political science professor at Zayed University in the United Arab Emirates who focuses on China’s relation with the Middle East. “The U.S. seems rudderless in the Middle East, and Europe doesn’t speak with one voice on foreign policy. China has a lot to offer, and the focus on economics and development rather than politics is attractive.”

There is a divide among analysts over China’s intentions regarding how far it wants to go in the security sector. Does Beijing want to just sell dangerous technology or eventually also replace the United States as a security guarantor? Julien Barnes-Dacey, director of the Middle East and North Africa program at the European Council on Foreign Relations, said China’s overall security dealings remain dwarfed by U.S. military relationships. But that may change. “China may be pulled into a greater regional role to secure its core interests, and this will likely include an enhanced security role,” he said. “But Beijing still appears to be cautious about wading in too deeply.”

Others say even its current limited role is highly destabilizing.

At a site in Dawadmi, Saudi Arabia, satellite images showed a burn pit disposing of solid-propellant leftovers from ballistic missile production. U.S. intelligence agencies were certain the missiles were being built with active Chinese assistance. Although the range and payload were not yet clear, ballistic missiles are a preferred means to deliver a nuclear weapon. Saudi Crown Prince Mohammed bin Salman has said if Iran succeeded in developing a nuclear bomb, Riyadh would soon follow. Building ballistic missiles fits well into that plan.

However, both Iran and Saudi Arabia are China’s comprehensive strategic partners. China could influence both against going nuclear, but it chooses to feed their appetite instead and justifies its military assistance as benign—merely creating a balance of power in the region.

In fact, China is effectively exacerbating the arms race in an already volatile region and gaining from the rivalry. The Saudi missile program’s expansion will make it even harder for the United States to constrain Iran’s missile program and hand it an excuse to keep it off the table in future negotiations.

Jeffrey Lewis, a weapons expert and professor at the Middlebury Institute of International Studies at Monterey, told Foreign Policy he first exposed the Dawadmi missile project in 2019 along with his colleagues at the Washington Post. “On a regional level, the proliferation of conventionally armed missiles is part of a regional arms race that could be very destabilizing,” even sparking a conflict between the United States and Iran. “On a global level, it is clear that existing mechanisms like the Missile Technology Control Regime, intended to slow the spread of ballistic missiles, are failing completely.”

China is increasingly coordinating with the Middle East’s despots and offering them full diplomatic support in exchange for energy and trade deals as well as diplomatic concessions on issues from Xinjiang human rights violations to the South China Sea dispute. It also wants to financially integrate the region so U.S. sanctions can no longer halt oil supplies and sanctioned actors are beholden to Beijing. For now, China is banking on Russia’s military muscle to stay out of military involvement in the region’s security conflicts. But Beijing cannot not stay on the fence forever in regional rivalries if it wants to be a world leader.