•To stop financing Moscow’s brutal wars, Berlin should help African countries develop their energy sectors.

By Vijaya Ramachandran

With the United States and United Kingdom banning Russian energy exports and the European Union announcing it will reduce Russian gas imports by two-thirds by the end of the year, the West is urgently debating how to replace Russian energy deliveries. The most crucial issue is the Russian gas on which Germany and other parts of Europe depend. From Washington to Berlin, politicians have announced they will be doubling down on wind and solar energy.

But while renewable energy production will be part of a long-term solution, the idea that it can replace Russian oil and gas quickly and at scale is disingenuous at best—and disastrous for Western economies and consumers at worst. The reasons should be clear to all but the energy-illiterate: Wind and solar power can replace some of the Russian gas used to generate electricity—but only when the wind blows and the sun shines, requiring substantial backup generation capacity, much of it powered by natural gas. What’s more, electricity is only part of the energy equation: The majority of Russian oil and gas is not used by power plants but to heat homes, run factories, and fuel cars, trucks, planes, and ships—none of which can be easily shifted to other fuels. If Western countries don’t want their economies to come to a standstill, oil and gas previously delivered from Russia needs to be sourced elsewhere.

Europe will therefore need a large, reliable supply of non-Russian fossil fuel for the foreseeable future. And any serious debate about energy security needs to focus very quickly on where future non-Russian supplies will be sourced. For Europe—especially Germany and the other countries most dependent on Russian supplies—part of the answer will be for Europe to stop looking east and start looking south to Africa.

Germany is the linchpin. For the past several decades, successive governments in Berlin have pursued a policy of maximizing the country’s dependence on Russian oil and gas, not least by turning off all but two remaining nuclear reactors. Gas will likely remain a critical source of Germany’s energy for years—perhaps decades—to come. It accounts for 25 percent of the country’s total primary energy consumption, and imports make up 97 percent of supply. Russia is the main source, followed by the Netherlands and Norway. (Germany has substantial supplies of natural gas of its own that could be accessed by fracking, but Berlin has banned the technology.) If Germany is to phase out Russian energy, it is not clear how Germans will heat their homes and power their factories.

Natural gas is cheap and reliable, burns twice as cleanly as coal, and is a critical input in many sectors—not just electricity generation. In Germany, 44 percent of gas was used for heating buildings in 2020, while industrial processes consumed 28 percent. Gas is the best and cheapest feedstock for the manufacture of synthetic nitrogen fertilizer, of which Germany is a critical supplier. (Russia and its ally Belarus are also major fertilizer producers.) Gas is also used in refining, the production of chemicals, and many other types of manufacturing. All of this is difficult—if not impossible—to replace with green energy anytime soon.

Germany has already announced it will further increase its use of coal, which overtook wind to become the biggest input for electricity production globally in 2021. Some of this will be lignite—the worst possible fossil fuel, dirtier than conventional coal and extracted in vast open-pit mines that litter the German countryside. But Germany has boxed itself into a corner with its energy policies—most crucially, the replacement of nuclear power with Russian gas—and does not have a lot of options. Already, the European Commission has given its absolution to countries replacing Russian gas with coal and producing higher emissions as a result.

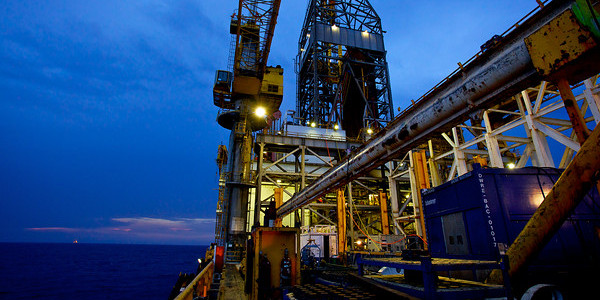

Germany must also be clear-eyed about its long-term energy future, including rethinking its current stance on carbon-free, non-Russian nuclear energy. Germany will also need substantial supplies of natural gas for the foreseeable future. If Berlin is serious about energy security, it should look to Africa, which has substantial natural gas production, reserves, and new discoveries in the process of being tapped. Algeria is a major gas producer with substantial untapped reserves and is already connected to Spain with several undersea pipelines. Germany and the EU are already working to expand pipeline capacity connecting Spain with France, from where more Algerian gas could flow to Germany and elsewhere. Libyan gas fields are connected by pipeline to Italy. In both Algeria and Libya, Europe should urgently help tap new fields and increase gas production. New pipelines under discussion currently focus on the Eastern Mediterranean Pipeline Project, which would bring gas from Israel’s offshore gas fields to Europe.

But the biggest African sources lie south of the Sahara—including Nigeria, which has about a third of the continent’s reserves, and Tanzania. Senegal has recently discovered major offshore fields. Very little of Africa’s gas has been exploited, either for domestic consumption or export.

Germany should take note of these opportunities. The proposed Trans-Saharan pipeline will bring gas from Nigeria to Algeria via Niger—going through some vast, ungovernable territory. If the project is completed, the new pipeline will connect to the existing Trans-Mediterranean, Maghreb-Europe, Medgaz, and Galsi pipelines that supply Europe from transmission hubs on Algeria’s Mediterranean coast. The Trans-Saharan pipeline would be more than 2,500 miles long and could supply as much as 30 billion cubic meters of Nigerian gas to Europe per year—equivalent to about two-thirds of Germany’s 2021 imports from Russia.

Unfortunately, the Trans-Saharan pipeline will likely take a decade or more to come to fruition and will present many challenges as it runs through areas plagued by conflict and insurgency. Nevertheless, the project should not be dismissed if Europe is taking energy security seriously. That’s because current gas suppliers are unlikely to fill the gap, as evidenced by last week’s announcement by a bloc of gas-producing nations that they would not be able to replace Russian gas in Europe. In contrast, Nigeria is enthusiastic about exporting some of its 200 trillion-cubic-foot reserves of gas. Nigerian Vice President Yemi Osinbajo has argued in favor of natural gas’ critical role, both as a relatively clean transition fuel and as a driver of economic development and foreign exchange revenues in Nigeria and other African countries.

A quicker way for Germany to tap African supplies would be to ship liquefied natural gas (LNG) from the West African coast. Unfortunately, as part of Berlin’s policy of making Germany dependent on Russian gas and in turn make Russia more dependent on Germany, the country has not built a single LNG import terminal. (Last week, Berlin announced it would finally change its policy and build LNG infrastructure.) LNG loading ports could also be built reasonably quickly in Africa. One example is the Greater Tortue Ahmeyin field, an offshore gas deposit straddling the maritime border between Senegal and Mauritania. Floating liquefaction plants above the offshore gas field produce, liquefy, store, and transfer the gas to LNG tankers that ship it directly to importing countries. When the field comes online next year, it will place Senegal and Mauritania among Africa’s top gas producers. While the initial production from this field will be small, it is slated to double in a few years, and the field sits within a larger basin of natural gas with substantially greater reserves. Elsewhere in Africa, too, gas production will continue to expand as projects in Tanzania, Mozambique, and other countries come online in the next few years.

Germany could kill two birds with one stone: It could stop financing Russian President Vladimir Putin’s brutal wars—and put its money where its mouth is on helping Africa develop and integrate economically. Until now, it has been part of Germany’s epic energy myopia to think that development can be done without the conventional energy sector. In fact, European representatives at the World Bank and other multilateral development institutions have done the opposite—lobbying hard to shut down the financing of natural gas projects in the developing world. Their hypocritical argument is that developing countries must decarbonize immediately—while they themselves ramp up coal and other fossil fuel production and otherwise enjoy an energy-intensive, rich-world lifestyle. This is even more absurd in light of the fact that sub-Saharan Africa currently generates only 4 percent of global carbon emissions and will remain energy-poor for decades to come—in fact, the average person in countries such as Ghana, Kenya, and Nigeria consumes less energy per year than a single American refrigerator. Not only will financing natural gas development in Africa generate urgently needed economic growth, but it will also be useful to Europe’s efforts to diversify away from Russia.

Sourcing much more gas from Africa—while also helping African countries to meet their own development goals—is something Germany and the rest of Europe can no longer ignore. If anything, it is a litmus test of how serious these countries are in this new age of energy insecurity.

Vijaya Ramachandran is the director for energy and development at the Breakthrough Institute. Twitter: @vijramachandran

Credit | Foreign Policy