Text by The German Institute for Global and Area Studies (GIGA) Hamburg (https://www.giga-hamburg.de/en)

Two years into the COVID-19 pandemic, there are signs that sub-Saharan Africa will experience a modest recovery in 2022. Yet at least in the first half of the year, the region will continue to suffer from inadequate provision and administration of vaccines. In addition, violent conflicts and structural weaknesses constitute considerable challenges. We present a selective list and analysis of “ten things to watch” in Africa in 2022.

- Politics: Last year saw a number of military coups, which may foreshadow future takeovers by armies in Africa. Pivotal elections lie ahead that could trigger the outbreak of violence, for instance in Kenya. Political heavyweight South Africa is in a severe socio-economic crisis that is engendering growing public anger, and the governing African National Congress is experiencing increasingly deepening internal rifts.

- Violent conflicts: The civil war in Ethiopia puts the state’s integrity at risk and could further undermine stability in the whole Horn of Africa. Jihadism represents a major security threat on the continent that needs to be tackled by African and international actors. A focus should lie on addressing root causes and on preventing crises.

- Development: It will take years for African countries to rebound from the pandemic’s socio-economic repercussions. Structural problems such as high poverty, inequality, and government debt hamper economic growth and the effects of climate change are strongly felt in many African countries already. The year 2022 will be crucial for devising the next steps for continental economic integration.

- International arena: Africa is a sought-after international partner. Several actors including China, Turkey, the United States, and the European Union and its member countries are vying for political and economic influence. This competition will further intensify.

Policy Implications

African countries getting their full share of COVID-19 vaccines will be important. African and international partners need to expand support for the COVAX initiative and boost public health systems. The approaching EU–African Union summit in February represents an opportunity to step up cooperation to strengthen regional economic integration, democratic development, and the fight against climate change. Based on its coalition agreement, the new German government should be a main driver of this partnership.

A Return of the Military in Politics?

The year 2021 was one of military coups (see Figure 1 below). In Guinea, President Alpha Condé was toppled after having won a contested third term. In Mali, the military ousted the transitional government in August, which had been installed following a previous coup in May 2020. In Sudan – generally not considered part of sub-Saharan Africa – the military re-captured power. Widespread protests against the takeover continue. Chad might also be added to the list: After its long-standing president, Idriss Déby, was killed in action while fighting rebels, the military declared his son, Mahamat Déby, the new president rather than speaker of parliament, as provided for in the Constitution.

Observers were quick to point out a new trend of the military returning to politics in Africa (Mwai 2021). While coups had declined over the previous decades, and only six occurred between 2010 and 2019, five coups have already taken place since 2020. However, the notion of a return of the military is a misconception: the army has remained a political force to be reckoned with in about 40 per cent of countries in the region (Basedau 2020), and coups as well as other manifestations of influence by the military have continued to be part of politics, especially in West and Central Africa.

Two major preconditions are most likely to trigger future military takeovers. First, coups typically occur in states in deep political crisis. Second, they mostly take place where the military was an important political actor previously. The more recent and the more entrenched the military’s role, the more likely future coups are, as it currently seems to be the case in Burkina Faso. Sudan is a case in point where the military dominated the ancien régime that itself fell through a coup and never accepted its demise. A third possible factor is diffusion – when coups in other countries demonstrate that such takeovers can be successfully staged. Hence, regional and international actors should sanction putschists, support civilian opposition against them, and demand a return to constitutional rule – not primarily through pushing for rapid elections but rather by addressing root causes including better governance and a professionalisation of the security sector.

Elections in 2022: The Risk of Unrest and Failed Transitions

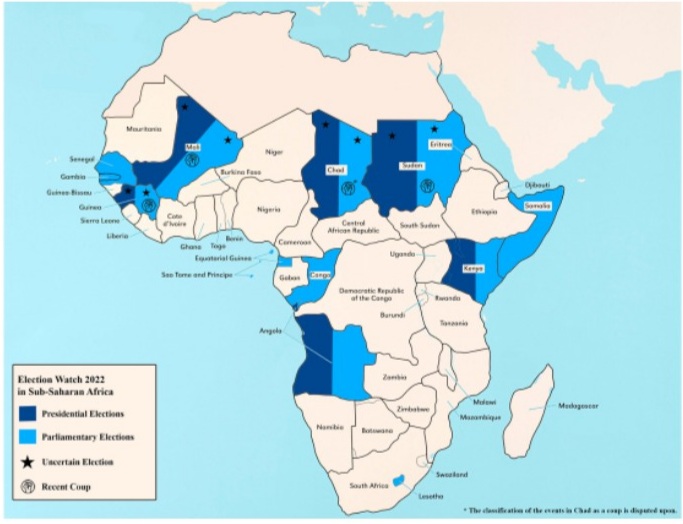

Several high-stakes elections will take place in sub-Saharan Africa in 2022. Parliamentary elections in Senegal in July 2022 aside, key polls in various countries concern the presidency (see Figure 1 below). Presidential elections (tentatively) scheduled for seven countries – Angola, Chad, Djibouti, Guinea, Kenya, Mali, and Somaliland – could raise tensions in two major ways.

First, elections in Angola, Kenya, and Senegal could trigger violence (ISS Today 2021). In Kenya, President Uhuru Kenyatta cannot stand for a third term. His attempt to secure influence by creating a large coalition through the so-called Building Bridges Initiative (BBI) failed when Kenya’s high court rejected the proposed constitutional change. The expected close contest between Deputy President William Ruto and veteran opposition leader Raila Odinga is likely to be highly disputed. It could even – as in 2008 – be accompanied by serious electoral violence, because the breakdown of the BBI undermined the prospect of amicable power sharing. The parliamentary elections in Senegal will also test that country’s political stability, as mounting tensions prior to the local elections in January show: The opposition has promised to heavily mobilise against President Macky Sall, who is rumoured to be seeking a third term in 2024, and his ruling coalition. In Angola, incumbent João Manuel Lourenço’s re-election bid constitutes a serious test for his reformist agenda, as he could build on his party’s dubious tradition to skew the electoral process in its (and his) favour.

Figure 1. National Elections in Sub-Saharan Africa in 2022 and Military Coups in 2021

Source: Own representation based on FreeVectorMaps.com.

Second, elections are scheduled in various countries that have recently experienced unconstitutional changes of government. While these elections are meant to bring – often fragile – transition periods to an end, it remains uncertain whether all polls will take place and, even more, if they can pave the way to real civilian rule. Sudan’s elections – originally envisaged for 2022 but then postponed to at least July 2023 – are set to mark the end of the transition that began with the ouster of President Omar al-Bashir in 2019. Yet, the recent coup shows that the military seeks to control the transition Prime Minister Abdalla Hamdok resigned less than two months after he returned to his position following an “agreement” with the coup leaders due to widespread protest against the deal. In Mali, the transitional government announced that, due to security concerns, elections will not be held in February as previously agreed and instead proposed holding elections in December 2025 only. The Economic Community of West African States (ECOWAS) responded with tough sanctions, including the suspension of financial transactions. In Chad and Guinea, the statements by Mahamat Déby and the Guinean transitional authorities that elections will be held in those countries in 2022 are questionable as they have not been accompanied by the announcement of specific dates. External engagement and, if necessary, pressure may be needed to follow up on these promises made.

Fragility Grows – Interdependent Forms of Violent Conflict

Violent conflict will continue to plague the region throughout 2022. According to the most current Fragile State Index, 14 out of the 20 most fragile states worldwide are located south of the Sahara; many of these conflicts could see further escalation. The four countries with the largest populations in sub-Saharan Africa, the Democratic Republic of the Congo (DRC), Ethiopia, Nigeria, and South Africa, either have been marred for a long time by violent conflict and protest or have turned more instable recently. Geographically, the Horn of Africa with Ethiopia being its most severe example, the Sahel, and the Lake Chad Basin, as well as large parts of Central Africa (DRC, Central African Republic, South Sudan) will remain hotbeds of violence. As a relatively new development, violent conflict has returned to Southern Africa, with a jihadist insurgency in Northern Mozambique and violent protests in eSwatini and South Africa.

Different types of violent conflict often mix. The transnationally most prevalent form will remain jihadist insurgencies (Faleg and Mustasilta 2021). Sub-Saharan Africa has become a new battleground of jihadism and it might continue to be contagious, especially in fragile countries such as Benin, Côte d’Ivoire, and Tanzania that neighbour countries already affected by such jihadist violence. To make matters worse, jihadism is often intertwined with interethnic violence – for example, in Burkina Faso, Mali, Mozambique, Niger, and Nigeria. Ethnic conflict is also leading to separatism in Cameroon, Ethiopia, and Nigeria.

Initiatives towards conflict resolution and prevention should take into account that the underlying causes of violence vary and are often structural. Long-term trends such as population pressure and deep-rooted socio-economic challenges (such as poverty and inequality) make societies fragile. Moreover, climate change has already led to migration and increased resource competition in some African countries. Weak states and poor governance render societies vulnerable to interethnic tensions and violent extremism. Unfortunately, international interventions mostly fail to address these underlying causes of conflict. UN and European powers have struggled to stabilise the Sahel, and some observers recommend dialogue with jihadists or even withdrawal – which could both prove to be a double-edged sword (Faleg and Mustasilta 2021). Curbing transnational support for jihadists seems more promising. Regarding COVID-19, economic effects are a reason to worry, especially in the long run as pandemic fallout on conflict will most likely have a longer incubation period. Any effort to alleviate the economic consequences will thus also serve to prevent violence in the middle and long term.

Ethiopia: Civil War and Delayed Political Reforms

In Ethiopia, the civil war between the Tigray People’s Liberation Front (TPLF) and the Ethiopian National Defence Force (ENDF), supported by ethnic Amhara militias and the army of Eritrea’s president, Isaias Afewerki, has been going on for more than a year. It has led to widespread atrocities against the civilian population in Tigray, but also in the Amhara and Afar regions. In summer 2021, the TPLF ousted the ENDF from Tigray, went on the offensive, and stood only about 200 kilometres away from Addis Ababa in November 2021. The war took yet another U-turn after Prime Minister Abiy Ahmed headed to the front to lead the fight against the rebels and called for all nationalist Ethiopians to follow him. The TPLF eventually backtracked. However, it seems that large numbers of drones that the ENDF purchased from Iran, the UAE, and Turkey were decisive game changers.

The beginning of 2022 is marked by uncertainty. TPLF leader Debretsion Gebremichael declared in December that his forces had retreated to Tigray to open an opportunity for peace talks, and the federal government in turn announced it would refrain from entering Tigray. Nevertheless, efforts by international actors, including the AU and the United States, to bring the parties to the negotiation table have so far not materialised. In addition to the civil war, Ethiopia is involved in a conflict with Sudan over the fertile al-Fashaga region, and talks with Egypt and Sudan over the filling of the Grand Ethiopian Renaissance Dam have stalled despite international calls to resume negotiations. The United States terminated Ethiopia’s eligibility for AGOA (African Growth and Opportunity Act) privileges due to the ongoing war and allegations that Ethiopian Airlines transported weapons to Eritrea.

Meanwhile, Abiy Ahmed has lost his former image as political reformer. His style of governance has become increasingly repressive, his government’s aid blockage of the Tigray region continues, and he has been accused of sympathising with religious figures calling for genocide, while thousands of ethnic Tigrayans are being held in camps simply due to their origin (Amnesty International 2021). Against this backdrop, it is hard to make an optimistic prediction for the things to come in 2022. The international community’s main concerns should be the delivery of aid to the needy population and continued pressure for peace negotiations. An arms embargo on both Ethiopia and Eritrea is long overdue and should be implemented in 2022.

Mounting Crisis in South Africa

Two recent events shocked South African citizens and symbolise the deep crisis in one of sub-Saharan Africa’s political heavyweights: Desmond Tutu, the former archbishop of Cape Town and a leading moral authority in the country, passed away on 26 December 2021. The Nobel Peace Prize laureate was an acclaimed anti-Apartheid and human rights icon who tried to forge a united society. Second, on New Year’s Eve, a fire apparently set by an arsonist ravaged the National Assembly buildings in Cape Town. In addition, the country saw violent protests and lootings – unprecedented since the end of Apartheid – in the Gauteng and KwaZulu-Natal provinces following former president Jacob Zuma’s incarceration in July 2021 after refusing to obey a court order. They left more than 300 people dead and demonstrate the fragility of the political situation in South Africa.

The COVID-19 pandemic and tough lockdown measures have exacerbated severe poverty and inequality in the country. The official unemployment rate has risen from 28.7 in 2020 to a record 34.9 per cent (46.6 per cent, if an expanded definition is used); more than 60 per cent of South Africans under the age of 25 who could work are currently jobless. On a positive note, it appears that South Africa has for now overcome the peak of coronavirus infections.

Yet, despite the decisive action taken against the pandemic, President Cyril Ramaphosa and his African National Congress (ANC) government have not been able to lead the country out of its severe socio-economic malaise. South Africa’s crisis is also a crisis of the ruling ANC, which is deeply split between supporters of Ramaphosa and the “traditionalists” that benefited from his predecessor Jacob Zuma’s misrule. Due to widespread misappropriation of public funds, dubbed “state capture,” large parts of the local administration are dysfunctional. The official Zondo Commission, which investigated corruption and misuse of funds for four years, will present its reports by the end of February 2022. This will further increase the pressure on Ramaphosa to act decisively against misbehaviour on the part of leading ANC members.

This will be even more important because in the country’s municipal elections on 1 November 2021, support for the former liberation movement fell below 50 per cent of the votes cast (45.6 per cent) for the first time. Public opinion polls show that President Ramaphosa is far more popular than his party, but in 2022, continued controversies within the ANC will continue to hamper his reform agenda. Discontent in the country will mostly likely persist if not further increase. According to surveys released in 2021, almost 80 per cent of South Africans think the country is heading in the wrong direction.

South Africa’s internal crisis also has severe implications for its regional neighbours. As South Africa is turning inwards, the region’s most powerful country has largely been unable to engage in regional crises in a meaningful and constructive way. This relates to the ever-increasing instability and authoritarian rule in neighbouring Zimbabwe, the insurgency in Mozambique’s Cabo Delgado region, and the brutal crackdowns on those protesting against the king in eSwatini (Mbuyisa and Mndebele 2021).

Mixed Prospects for Regional Integration

Measured against the ambitious goal of doubling intra-African trade to 25 per cent of total trade in 2022, the African Continental Free Trade Area (AfCFTA) has made little progress: intra-African exports have declined in absolute terms, making up a measly 14 per cent of total exports in 2019, even before the pandemic hit. COVID-19 has presented further challenges, with many African countries closing their land borders, thus inhibiting trade with neighbours.

Nevertheless, there are reasons for cautious optimism. The AfCFTA’s promise to deepen trade relations on the continent is highlighted by international organisations as an important cornerstone in the continent’s post-pandemic recovery. It could lift an additional 30 million people (1.5 per cent of the continent’s population) out of extreme poverty by 2035 according to recent World Bank projections. In 2021 multiple African countries devised national strategies to boost export capacity. The ongoing AfCFTA negotiations made important strides in 2021 and are expected to continue at full speed in 2022. According to a recent survey, CEOs in 46 African countries expect the AfCFTA to lead to enhanced trade. Intra-African trade, which is mainly land-based, could benefit the most in 2022, as the costs of international container shipping are exploding due to both the pandemic and global value chains being in disarray, making intra-African trade potentially more profitable.

The picture is somewhat less rosy for the ECO, West Africa’s planned common currency. Increasing budget deficits prompted West African heads of state to suspend the convergence pact for 2020–2021 and to publish a new roadmap postponing the launch of the common currency from 2020 to 2027. Apart from delays due to the ongoing pandemic, a lack of regional unity persists and is likely to derail the project further. The former French colonies using the CFA franc (XOF) are anxious to replace their currency, established in colonial times, with a West African one and could transition easily as they are already in a currency union. By contrast, Nigeria and Ghana, West Africa’s largest anglophone economies, just introduced their own central bank digital currencies, which some interpret as showing a lack of faith in the common vision. Key questions such as the exchange-rate regime and the extent of fiscal integration remain undecided. The roadmap’s 2022 milestone – fixing the level of central bank reserves and pooling reserves – will prove decisive for the future of the common currency project.

Corona Pandemic: Low Vaccination Rates, Modest Economic Recovery

Africa is currently seeing a steep rise in infections driven by the Omicron variant, but mortality rates remain low. This is good news: a more fatal variant of the virus could have severe consequences, as large parts of the sub-Saharan African population will remain unvaccinated in 2022. According to estimates by the World Health Organization, at most only 40 per cent of Africa’s population (including North Africa) will be vaccinated by May 2022 and it will take until August 2024 to reach 70 per cent (World Health Organization 2021). In many countries, hardly any people have been vaccinated to date, including the DRC with a vaccination rate below one per cent and Nigeria with about 2 per cent, a situation that seems unlikely to change fundamentally in 2022. Even though vaccines are arriving in increasing numbers in sub-Saharan Africa – slowly addressing but certainly not overcoming the massive global vaccine inequity – distribution and administration of the doses is seriously lagging.

African governments have not resumed the drastic lockdown measures of early 2020 that contributed to severe economic recessions in several countries. Most countries have fared better in 2021, and this trend will most likely continue – supported by recovery elsewhere and high commodity prices. Yet, the recessions plus the ongoing pandemic-induced growth slowdown continue to impact poverty. Governments did not have policies in place to protect the poor, and this situation remains unchanged. The World Bank estimates that the number of poor people (those living on less than USD 1.90 per day) rose by 23 million in 2020 alone. The increasing poverty may have since flattened out, but it is still above the baseline estimate without the pandemic. Even this baseline scenario shows a continuous increase in the number of extremely poor Africans of approximately five million per year because of strong population growth that outweighs the positive effect of economic growth on poverty. A strong growth rebound will be important to change this dire picture, but the current uncertainties and the arrival of the next wave cast doubts on whether this will happen. Further, if the growth rebound is mainly driven by higher commodity prices, it will reduce poverty less than growth driven by domestic factors would.

Even with Africa’s governments finding the right policies and economies adjusting to a new normal, some of the socio-economic impacts of the pandemic will be long-lasting: During the early phases of the pandemic, many countries closed schools despite potentially severe consequences for the children concerned. In Uganda, for example, schools were fully closed for 60 weeks between March 2020 and October 2021. Yet, there was huge variation: There were no school closures in Burundi, Ghana (fully) closed its schools for 10 weeks, Nigeria closed its for 18 weeks, and Zimbabwe its for 34 weeks. COVID-related restrictions, should they become necessary again in 2022, need to be carefully weighed against long-lasting socio-economic consequences.

Africa’s Climate Policy between Adaptation Needs and “Green Colonialism”

The year 2022 will see an intensified debate about Africa’s (future) greenhouse gas emissions, its role in climate change mitigation efforts, and potential tensions with economic development. One side claims that decarbonising Africa’s economic development is important because its strongly growing population will make it an important emitter even if emissions per capita and, in fact, energy and GDP per capita, remain low (Goldstone 2021). The other camp sees this fear as exaggerated. According to its proponents, Africa needs (some) more fossil energy to develop and its energy systems are already decarbonising to a large extent (Moss 2021). To reinforce this view, they highlight the very low emissions of Africa to date, stress the historical responsibility of big emitters, and even brand some global climate policies as “green colonialism” (Ramachandran 2021). These crucial debates will gain prevalence, as global climate policies are increasingly affecting African economies. This includes actions by international financial institutions, carbon taxes and related border-tax adjustments, and other measures such as the decision of France, Germany, the US, the UK, and the EU to enhance support for South Africa’s energy transition pledged at the 2021 global climate negotiations (Conference of the Parties, COP26) in Glasgow.

It will be worthwhile to watch how this specific pledge develops, as negotiators prepare for an “African COP”: COP27 is scheduled to take place in November in Sharm el-Sheikh, Egypt. Most of sub-Saharan Africa’s least developed countries want the focus of this conference to be on adaption to climate change. Here, COP26 failed to deliver as no concrete actions, in particular on financing “loss and damage,” were agreed upon. It remains to be seen whether the next COP can bring “big solutions” in this sensitive arena, though scaled-up support to Africa’s most vulnerable countries is a likely outcome.

Various Options: Africa’s International Partners

The eighth ministerial Forum on China–Africa Cooperation (FOCAC) took place in November 2021, while Turkey’s president Recep Tayyip Erdoğan hosted a much publicised “Turkey–Africa Partnership Summit” in Istanbul in December. These meetings designed to foster closer economic and political ties occurred exactly when countries across the world were closing their borders for travel from Southern African countries in response to the Omicron variant, a move heavily criticised by African observers and others. In 2022 China will further increase its footprint on the African continent and – going by credible reports – plans to construct a permanent military base in the small West African country of Equatorial Guinea (Tanchum 2021). This will be China’s second base in Africa, in addition to the one in East Africa’s Djibouti. In line with its expanding global ambitions, China is adding a military component to its traditional economic and political relations with the continent.

In its first year in office, the administration of US president Joe Biden sought to counter China’s influence, also in Africa. But as of now the US government has not formulated a coherent Africa policy. Secretary of State Antony Blinken embarked on an online visit to Kenya and Nigeria in April, and in November 2021 made a three-nation visit in person to Kenya, Nigeria, and Senegal. The State Department also invested considerable resources in helping solve the crisis in Ethiopia. Yet the significant pressure imposed on the Ethiopian government – a long-time US ally in the Horn of Africa – to end the military campaign in the Tigray region was met with strong resistance. Among the 110 participating countries in President Biden’s signature Summit for Democracy, 17 were from Africa. Apart from Angola and the DRC, these were roughly the most democratic ones on the continent. However, the important question remains of whether the Biden administration will follow up on the Summit for Democracy, for instance by strengthening support to more democratic countries in Africa.

These activities demonstrate that the EU and its member states are no longer Africa’s partner of choice by default. The EU’s Global Gateway initiative can be seen as a means to counter China’s Belt and Road Initiative, as African countries are the biggest beneficiaries outside Asia of the Chinese infrastructural programme. Yet, the “new” EU strategy currently appears to be more of a bundling and repackaging of existing investment programmes and attempts to stimulate private investment beyond Europe. The amount of additional funding is limited. The upcoming EU–AU summit, to be hosted by the French Council Presidency in Paris in February, will offer an opportunity to strengthen the bonds between African and European partners and to devise new priorities and programmes, for instance in fighting climate change. Strengthening the provision of COVID-19 vaccines through the international COVAX initiative is of utmost importance.

Continuity in the Making: The Africa Policy of Germany’s New Government

The contours of the new German government’s Africa policy are not yet entirely clear – but some early decisions indicate future avenues. First, the coalition desisted from merging the Federal Foreign Office (FFO, now led by Annalena Baerbock from the Greens) with the development ministry (BMZ, led by Svenja Schulze, Social Democrats). The discussion about whether to fuse them regularly comes up before and after national parliamentary elections in Germany. The country now remains the only member of the OECD Development Assistance Committee with an independent development ministry (OECD 2021). Representatives from the FFO regularly complain about double structures and – despite some improvements – difficulties aligning the two ministries, irrespective of whether the two given ministers hail from the same party. Partner countries of the BMZ (see Figure 2) also do not always match Foreign Office priorities. It remains to be seen whether the new government will strengthen interdepartmental coherence.

Figure 2. German Development Cooperation Partners in Sub-Saharan Africa

Source: Own representation based on FreeVectorMaps.com.

As expected, “Africa” featured prominently neither in the coalition talks nor in the coalition agreement. Published in December 2021, the coalition agreement does not herald a drastic change of Germany’s established collaboration with Africa – similar to the Biden administration in the United States (von Soest 2021). The coalition partners stress the issues of peace, prosperity, sustainable development, fighting the climate crisis, and strengthening multilateralism as main areas of focus (SPD, Bündnis 90/Die Grünen/FDP 2021: 156). They foresee further support for the AfCFTA and the G20 Compact with Africa, the latter having been launched by Germany’s previous “grand coalition” government. The Compact with Africa seeks to improve the conditions for private-sector activities and investment in selected partner countries. Interestingly, the coalition agreement specifically mentions only one subregion in Africa, the Sahel, and promises to “make permanent” Germany’s civilian stabilising measures there.

It is not yet clear whether and how the government’s welcome emphasis on the global protection of human rights will translate into changed German and European policies with African partners. Furthermore, the document does not specify whether Germany’s new government will take further steps to increase the coherence between different policy fields with relevance for African countries. Germany’s G7 presidency in 2022 with its focus on tackling climate change and the COVID-19 pandemic, as well as strengthening democracies around the globe, might lead to increased attention for Africa as all three areas are of great importance to the continent. An important initial test for the new government’s foreign and security policy will be whether it prolongs its participation in the UN and EU military missions in Mali.

References

Amnesty International (2021), Ethiopia: Tigrayans Targeted in Fresh Wave of Ethnically Motivated Detentions in Addis Ababa, 12 November, accessed 5 January 2022.

Basedau, Matthias (2020), A Force (Still) to Be Reckoned With: The Military in African Politics, GIGA Focus Africa, 5, July, accessed 28 December 2021.

Faleg, Giovanni, and Katariina Mustasilta (2021), Salafi-Jihadism in Africa. A Winning Strategy, Policy Brief 12/2021, European Institute for Security Studies, accessed 28 December 2021.

Goldstone, Jack A. (2021), The Battle for Earth’s Climate Will Be Fought in Africa, accessed 12 January 2022.

ISS Today (2021), African Elections to Watch in 2022, accessed 10 January 2022.

Mbuyisa, Cebelihle, and Magnificent Mndebele (2021), ESwatini Killings: All the King’s Men vs the People, New Frame, accessed 11 January 2022.

Moss, Todd (2021), Why the Climate Panic About Africa Is Wrong, in: Foreign Policy, 6 December, accessed 11 January 2022.

Mwai, Peter (2021), Sudan Coup: Are Military Takeovers on the Rise in Africa?, BBC Africa, 26 October, accessed 28 December 2021.

OECD (2021), OECD Development Co-Operation Peer Reviews: Germany 2021, accessed 11 January 2022.

Ramachandran, Vijaya (2021), Rich Countries’ Climate Policies Are Colonialism in Green, in: Foreign Policy, 3 November, accessed 11 January 2022.

von Soest, Christian (2021), The End of Apathy: The New Africa Policy under Joe Biden, GIGA Focus Africa, 2, March, accessed 11 January 2022. SPD, Bündnis 90/Die Grünen/FDP (2021)

Koalitionsvertrag 2021-2025: mehr Fortschritt wagen: Bündnis für Freiheit, Gerechtigkeit und Nachhaltigkeit, accessed 11 January 2022.

Tanchum, Michaël (2021), China’s New Military Base in Africa: What It Means for Europe and America – European Council on Foreign Relations, ECFR Blog, 14 December, accessed 11 January 2022.

World Health Organization (2021), Africa Clocks Fastest Surge in COVID-19 Cases This Year, but Deaths Remain Low, accessed 11 January 2022.

Credit |The German Institute for Global and Area Studies (GIGA) Hamburg