By Adam Tooze

As NATO meets to discuss the tension on the Russian border to Ukraine, and the papers fill with denunciations of Putin’s aggression, I still find it useful to return to the framework I developed in Crashed for analyzing the intersection of geopolitics and economics and the rise of Russia as a challenger. This framework consists of three basic propositions.

The first is that though it is tempting to dismiss Putin’s regime as a hangover from another era, or the harbinger of a new wave of authoritarianism, it has the weight that it does and commands our attention because global growth and global integration have enabled the Kremlin to accumulate considerable power. The sophistication of Russian weaponry and its cyber capacity betoken the underlying technological potential of the broader Russian economy. But what generates the cash is global demand for Russian oil and gas. And Putin’s regime has made use of this. It is reductive to think of Russia as a petrostate, but if you do indulge in that simplification you must recognize that it is a strategic petrostate more like UAE or Saudi than an Iraq, or Algeria.

Russia is a strategic petrostate in a double sense. It is too big a part of global energy markets to permit Iran-style sanctions against Russian energy sales. Russia accounts for about 40 percent of Europe’s gas imports. Comprehensive sanctions would be too destabilizing to global energy markets and that would blow back on the United States in a significant way. China could not standby and allow it to happen. Furthermore, Moscow, unlike some major oil and gas exporters, has proven capable of accumulating a substantial share of the fossil fuel proceeds. Since the struggles of the early 2000s, the Kremlin has asserted its control. In the alliance with the oligarchs it calls the shots and has brokered a deal that provides strategic resources for the state and stability and an acceptable standard of living for the bulk of the population. According to the WID-er data after the giant surge in inequality in the 1990s, Russia’s social structure has broadly stabilized.

Putin’s regime has managed this whilst operating a conservative fiscal and monetary policy. Currently, the Russian budget is set to balance at an oil price of only $44. That enables the accumulation of considerable reserves.

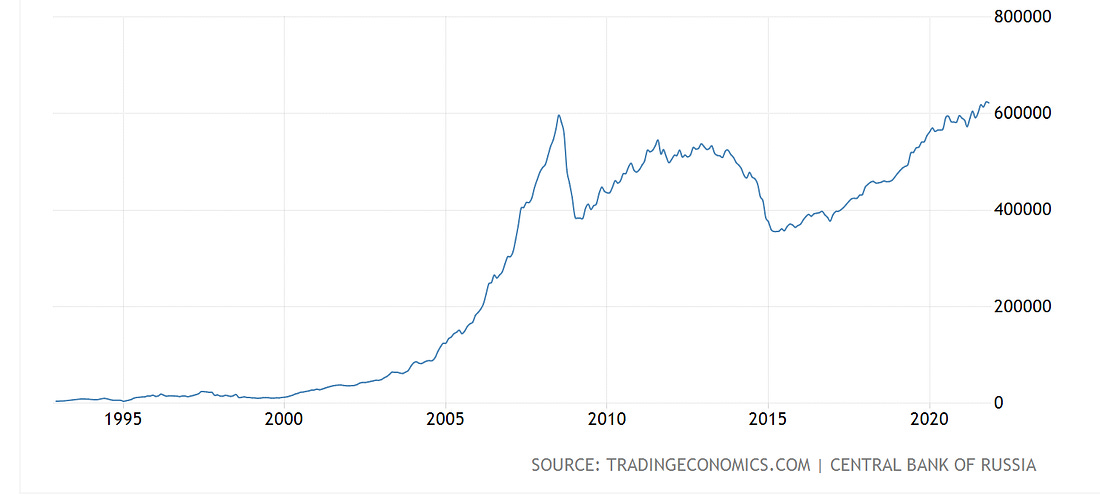

If you want a single variable that sums up Russia’s position as a strategic petrostate, it is Russia’s foreign exchange reserve.

Source: Trading Economics

Hovering between $400 and $600 billion they are amongst the largest in the world, after those of China, Japan and Switzerland.

This is what gives Putin his freedom of strategic maneuver. Crucially, foreign exchange reserves give the regime the capacity to withstand sanctions on the rest of the economy. They can be used to slow a run on the rouble. They can also be used to offset any currency mismatch on private sector balance sheets. As large as a government’s foreign exchange reserves may be, it will be of little help if private debts are in foreign currency. Russia’s private dollar liabilities were painfully exposed in 2008 and 2014, but have since been restructured and restrained.

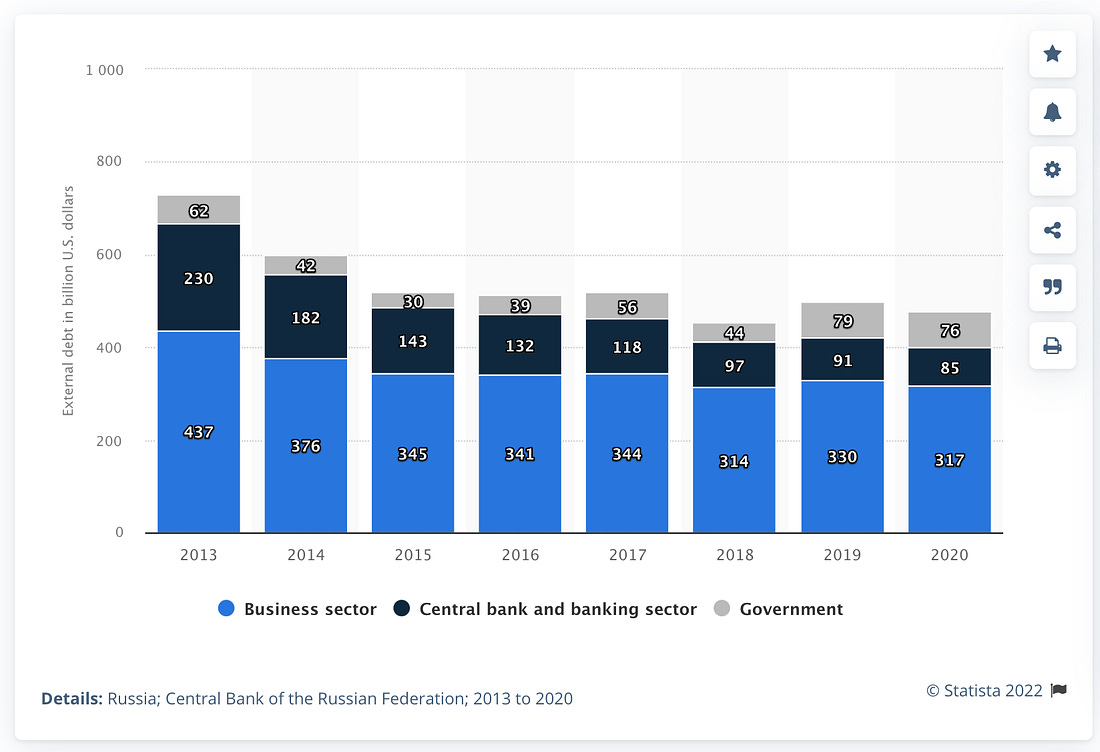

Source: Statista

According to data released by the Bank of Russia, Nominal foreign debt of banks and non-financial companies (corporate foreign debt) increased by US$6bn to US$394bn in 2Q21 (c.25% of GDP), easily covered by the foreign exchange reserves.

This strong financial balance means that Putin’s Russia will never experience the kind of comprehensive financial and political crisis that shook the state in 1998.

Nor was it by accident that it was as those foreign exchange reserves approached their first peak in 2008 that Putin began to articulate his determination to end the period of Russia’s geopolitical retreat. This is the second key element of the diagnosis.

Putin laid out his position in no uncertain terms in his sensational speech to the Munich Security Conference in February 2007 in which he outlined his comprehensive critique of Western power and Russia’s refusal to accept any further eastward expansion of NATO.

Today, China’s fundamental opposition to American hegemony articulated from within the global economy dominates the global scene. But the first to expose the fact that global growth might produce not harmony and convergence but conflict and contradiction, was Putin in 2007-8.

Putin’s stance produces outrage in the West. His assertion of Russia’s autonomy by all means necessary exposes the vanity of the post-Cold War order, that assumed that the boundary between different forms of power – hard, soft and financial – would be drawn by the Western powers, the United States and the EU, on their own terms and to suit their own strengths and preferences. The West has itself always employed a blend of strategies – financial pressure, soft power and military force – to achieve its goals. Russia’s challenge has forced a reshuffling of that pack and new combinations of diplomatic persuasion, soft power, financial and ultimately military threats and coercion. That this should be happening in Europe compounded the scandal.

The third essential point is that the consequences of this resurgence of Russian power depend on where you are and how you are set up to meet the challenge.

In Eastern Europe the crucial question is how Russia’s neighbors, whether former Soviet Republics, or former Warsaw Pact members navigated the staggering economic and social shocks of the 1990s. In this regard, Poland and the Baltics are at one end of the spectrum. They have rebounded from the 1990s crisis, have relatively high-functioning post-Communist polities and gained membership in NATO and EU in early waves of expansion. Ukraine is, in every respect, at the opposite end of the spectrum.

What makes Ukraine into the object of Russian power is not just it geography, but the division of its politics, the factional quality of its elite and its economic failure.

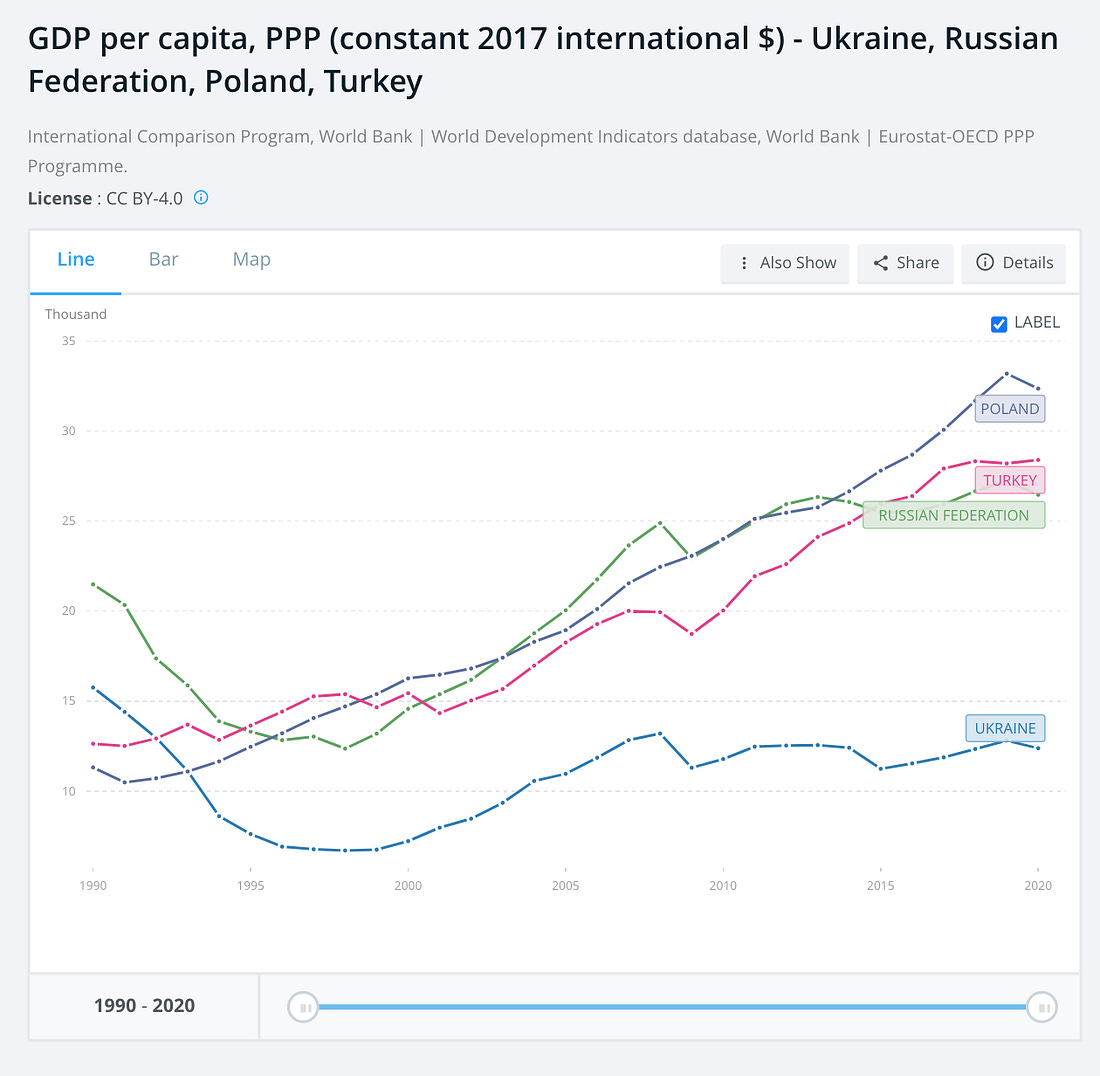

The end of the Soviet Union may have given Ukraine independence but for Ukrainian society at large it has been an economic disaster. Like Russia, Ukraine suffered a devastating shock in the 1990s. GDP per capita in constant PPP terms halved between 1990 and 1996. It then recovered to 80 percent of its 1990 level in 2007 and has stagnated ever since. Thirty years on, Ukraine’s GDP per capita (in constant PPP dollars as measured by the World Bank) is 20 percent lower than in 1990.

Source: World Bank

Ukraine’s experience contrasts sharply with that of Russian Federation which since the 1998 crisis has seen much more dramatic and sustained recovery. It also contrasts painfully with the growth trajectory of Ukraine’s neighbors Turkey and Poland.

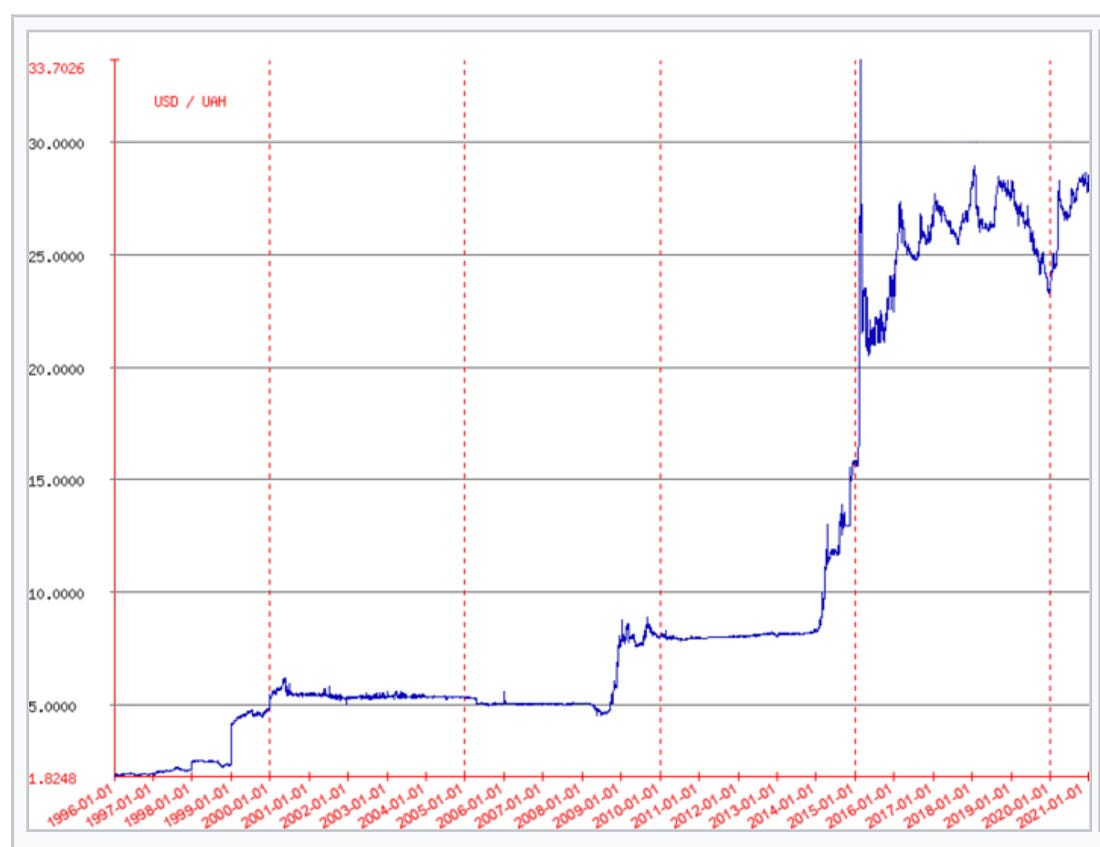

GDP per capita numbers paint a picture of painful stagnation. In addition, Ukraine’s weakness have left it vulnerable to repeated and painful foreign exchange and financial crises, best summarized by the erratic chart of the hryvina’s devaluation against the dollar and euro. There were big shocks in the late 1990s. In 2008. In 2014-5. Since 2015 the hryvina has swung around a new plateau. Given the depreciated level of the currency, in percentage terms the swings are now smaller. But Ukraine continues to be a fragile ward of the IMF.

Source: Wikipedia

Russian nationalist simply dismisses Ukraine’s claim to statehood altogether. That is propaganda. But what is clearly true is that Ukraine’e elite have not come up with a formula for delivering the material basis of legitimacy, i.e. a minimum of stability and sustained economic growth. Economic frustration compounds the divisions between regions, language groups, factional interests. Since independence, the oligarchic super-rich have played a baneful and disruptive part in Ukraine’s politics.

When President Zelensky declared after his first encounter with Putin in the talks in Paris in December 2019, “Ukraine is an independent, democratic state, whose development vector will always be chosen exclusively by the people of Ukraine”, we should bear these basic economic facts in mind. Clearly, Zelensky wished to insist on Ukraine’s sovereignty vis a vis an overmighty Russia. But if sovereignty consists in determining a development vector – which does seem like a good definition – what can one say about Ukraine’s sovereignty? At best it could be described as a desperate and so far vain search for a development model that could command the support of a majority in Ukraine.

That desperate search was made more urgent by the rising geopolitical tension announced by Putin’s speech in 2007 and by the financial shock of 2008. But it was also made more dangerous.

The basic options as discussed before 2014 were alignment with Russia, alignment with the EU-NATO or balancing between the two. Balancing between the two was the mode preferred in the 1990s and early 2000s. But by the mid 2000s in the wake of the color revolutions in Georgia and Ukraine in 2004, with both Poland’s prosperity and Russia’s ambition increasingly evident, the choices began to seem more stark.

Then in 2008, the Bush administration sought to decide the issue. It encouraged both Georgia and Ukraine to aspire to NATO membership and wrangled the other NATO members, at the NATO Bucharest conference in April 2008 into promising them membership. This confirming Russia’s worst fears. Ever since Ukraine’s politics has been torn by the scale of this choice. The worst consequences were graphically illustrated in Georgia.

Following the Bucharest NATO summit, Georgia’s ambitious leadership under President Mikheil Saakashvili concluded that to expedite NATO membership it would need to resolve outstanding issues with the breakaway region of South Ossetia. It also imagined that it had received a green-light from Washington. In August 2008, just weeks ahead of the Lehman crisis, Moscow’s massive military reaction to Georgia’s offensive in South Ossetia sent a clear and decisive message. Do not attempt to move forward on NATO’s ill-judged Bucharest commitments.

If that was not enough, economic and financial crisis in US and Europe halted any further moves in that direction. In 2008 Ukraine was immediately thrown into appealing to the IMF. Given its reliance on heavy-industrial exports, Ukraine was one of the economies worst hit by the 2008 shock.

By 2013, Kiev was desperately trying to play off IMF, EU and Russia looking for a deal. The result in 2013 was a winner takes all bidding war between the EU and Russia for influence over Ukraine’s economy. Yankukovych’s corrupt regime first encouraged its population to believe that it was swinging towards the EU. Then, faced with the niggardly European financial terms, and with a far more lucrative offer from Moscow in hand, it swung abruptly back towards Russia. That triggered the Maidan revolution. With the West hastening to recognize the revolution, Yanukovych was unwilling to stand and fight. Faced with a fait accompli Russia decided to save what could be saved. In 2014 it annexed Crimea and intervened to create Russian-backed separatist Republics in the Eastern Donbass region.

This is where the current media story typically begins: “Russian aggression against sovereign Ukraine in 2014”.

Desperate to hold the Kiev regime together, the West instrumentalized the IMF under Christine Lagarde to provide financial assistance to Kiev. This was the first time that the Fund has made a program for a country in Ukraine’s unstable condition, with an ongoing conflict on its territory. But neither the EU nor the US had any intention of backing Ukraine sufficiently to win the war in the East. Instead, the Obama administration backed away and handed off the Ukraine crisis to France and Germany. In the so-called Normandy format negotiations – amidst the eruption of the Eurozone clash with the new Syriza government in Athens and the swelling refugee crisis (the original polycrisis) – Berlin and Paris =shepherded Ukraine into the Minsk II agreement in 2015. After years of alienation (remember Snowden 2013) it was a moment of restored US-German harmony.

The Minsk agreement of 2015 is key to the current crisis. The original deal was a reflection of Russia’s massive military superiority over Ukraine but also Russia’s unwillingness to escalate to the point of full-scale invasion. The deal satisfied Russia because it promised a decentralized Ukraine with language rights guaranteed for Russian speakers. That in Moscow’s view was enough to ensure that Ukraine would not slide into the Western sphere of influence. If no progress was made on implementing the deal, Ukraine would be left in a state of frozen conflict. The ongoing conflict might not stop IMF support, but it would rule Ukraine out as a candidate for closer integration with either the EU or NATO. But it is also a painful provisorium. It is deeply unsatisfying to the increasingly nationalist tone of politics in Kiev. Moscow found itself backing the Donbass region and having to adjust to life under a sustained sanctions regime imposed by the US and the EU.

Resolving the Minsk agreement impasse is what the argument has been about since 2019 when Zelensky was elected on a peace-ticket and President Macron of France took steps to revive the process in the hope of bringing Russia out of the deep freeze.

With Trump in the White House and increasing concern about China, France did not want to persist with the status quo. An independent Franco-European diplomacy towards Russia has been a fantasy since the days of De Gaulle. Germany has continued its economic relations with Russia regardless of the Ukraine crisis, notably in the energy sector. The agreement between Gazprom, Royal Dutch Shell, E.ON, OMV, and Engie to build Nordstream 2 was signed in the summer of 2015 and though it was put on ice, German permits were issued in January 2018 and construction on the German end began in May of that year.

But moving beyond the Donbass impasse requires concessions from both sides. Russia would need to concede at least independent monitoring of elections and institution-building in the Donbass segment it controls. And Ukraine and Russia would need to agree on the ultimate goal. To satisfy Russian concerns, Minsk envisioned a high degree of autonomy for the Eastern regions. The most Kiev is willing to agree to is the incorporation of Donbass into general structure of federation which does not go anywhere near far enough for Russia. Furthermore, after years of struggle Ukrainian nationalists regard any steps towards the actual implementation of the Minks agreement in a form that would be acceptable to Moscow, as an act of treason.

So if this is the backdrop to the impasse in Ukraine, and if 2019 seemed to open a new era of engagement, what I have been trying to figure out is what explains the current escalation to the point in which since the spring of 2021 we have had two major war scares in the period of 12 months. Furthermore, these are war scares of a different order of magnitude. .

Russian military analysts will tell you the Russia has been building capability for a while so it may simply have been a matter of time before they decided to wield this instrument of coercion.But that still begs the question of timing.

It is sometimes suggested that Putin needs a war scare for domestic political purposes. The annexation of Crimea in 2014 earned him a huge popularity bump. That has dissipated. There is little evidence from Lavarda polling data to suggest that the Russian population would welcome a new war and particularly not one with Ukraine.

It is true that since 2014 the gloss has come off Russia’s economy. Putin’s regime can no longer offer a good news story of an improving welfare bargain. In 2018 it raised the pension age, further undermining morale. As analysts at the Carnegie center have remarked, the Putin-era social contract – “you provide for us and leave our Soviet-style social handouts alone, and we’ll vote for you and take no interest in your stealing and bribe-taking” – has worn thin. In the autumn elections to the Russian parliament the legacy Communist party gained strength. But, again, that hardly provides a good reason for a sudden escalation to the current level of military tension.

The more compelling logic is driven by the tensions within the Minsk compromise, Russia’s geopolitical concerns about America’s stance, and Putin’s own political clock.

Inside the Kremlin, Putin’s own timeline is crucial. In 2024 he faces a choice as to whether to continue in power or to begin to prepare his final exit. Russia could step away from the Ukraine issue. But Putin is too dug in. He wants to resolve Ukraine. This does not mean annex it. It means achieving what the struggle between 2007 and 2015 was about i.e. drawing a line on western expansion. That needs to be achieved both by consolidating a Russian veto in Ukrainian politics and driving home the message to the West not to attempt a further expansion. If 2024 is the date that is on Putin’s mind, then this overlaps with the term of the Biden Presidency. So, setting the terms of Russo-US relations on the issue as early as possible must be a priority for the Kremlin. The Biden administration has clearly signaled that its priority is China and that it is willing to pay a political price for retrenching its strategic position (Afghanistan), perhaps that opens the door in Ukraine.

Then there are internal dynamics within Ukraine. The Western media tend to treat Russia’s commentary on Ukraine as purely instrumental talk. But what if we take seriously what the Russians say? In that case what they are concerned about is something like the Georgian scenario. An over-ambitious or desperate nationalist regime in Kiev, encouraged by loose Western talk about NATO membership, attempts, through force, to reincorporate Donbass. That would require Moscow to react with massive force. Better to resolve the issue on Moscow’s own terms by making clear the vast imbalance in military power and forcing the US to engage with the diplomatic process, out-maneuvering Berlin and Paris, which Moscow regards as helpless and pro-Ukrainian.

In 2018, Putin publicly declared that a Ukrainian attempt to regain territory in the Donbas region by force would unleash a military response.

The election in 2019 election of Volodymyr Zelensky was seen as potential opening. He ran as a peace candidate. He returned to the Normandy format negotiations and Russia put a lid on any violent clashes in Donbass. But Zelensky’s popularity has collapsed. Like all his predecessors he faces a choice between Russophone opposition based in the east of the country, and the nationalists rooted in Ukraine’s west. Like all his predecessors he is trying to deliver for the electorate whilst negotiating with the IMF. Ukraine’s economic situation continues to be miserable.

The divisions within Ukrainian politics continue to be extreme, with the nationalist exerting a whip-hand. In March 2020 Zelenskiy’s chief of staff, Andryi Yermak, met with the Putin’s point man Dmitry Kozak, and agreed on a special Advisory Council in which Ukrainian officials would discuss the peace process with representatives of the Russian-backed separatist governments. On his return to Kiev, Yermak was slapped with criminal charges by the Ukrainian security services and faced accusations of treason in parliament. This confirmed Moscow’s view that nationalist zealots in Ukraine call the shots.

Meanwhile, the NATO-Ukraine issue continues to bubble.

In early December 2019 the Ukrainian parliament adopted a resolution “regarding priority steps to ensure Ukraine’s Euro-Atlantic integration and acquire Ukraine’s full membership in the North Atlantic Treaty Organization.”

Nor was this simply an appeal from the Ukrainian side. According to Carnegie Moscow center’s Vladimir Frolov, the moment when Moscow’s strategic patience regarding the Zelensky government finally snapped was in June 2020, when NATO decided to grant Ukraine the status of Enhanced Opportunities Partner.

This was welcomed by a representative of Zelensky’s party as follows:

Lisa Yasko, Ukrainian MP, Servant of the People Party: NATO’s decision to grant Ukraine Enhanced Opportunities Partner status is great news. The Ukrainian government has been working on this issue since autumn 2019. Earlier obstacles resulting from misunderstandings with Budapest regarding Ukrainian language policy and education reforms have been resolved thanks to fruitful bilateral dialogue with Hungary. Enhanced cooperation between Ukraine and the NATO alliance is of the utmost strategic importance for regional and global security. EOP status gives us new opportunities in Ukraine, in Brussels, and across the globe. In particular, this opens up new possibilities for the further exchange of information and intelligence, mutual training, and the participation of the Ukrainian military in NATO missions. At the same time, it is important to underline that our claim for a NATO membership action plan remains valid. With this in mind, Ukraine continues to implement reforms in the security and defense sectors. In 2020 this includes the reform of military ranks in line with NATO standards. President Zelenskyy has also presented a bill on Security Service reform. This reflects our ongoing commitment to greater Euro-Atlantic integration. Over the summer of 2020, there was talk in Kyiv of attaining the status of Major Non-NATO Ally, which would remove virtually all restrictions on military cooperation with the Americans.” That is probably the main Russian worry at this point.

As far as the Carnegie team working under Dmitri Trenin can judge, this was a crucial turning point.

Moscow, however, did not immediately move to a war footing. In the second half of 2020 it had to deal with two other major crises in its immediate neighborhood. In August the rigged presidential elections in Belarus triggered an unprecedented storm of protest. In September 2020 war broke out between Armenia and Azerbaijan, with Azerbaijan, backed by Turkey, scoring a major victory. A fragile peace was achieved in November 2020 with Moscow acting as the broker.

Both of these crises could have provided a reckless regime in Moscow with

opportunities for dramatic intervention. In neither case did Moscow push hard. In the Caucasus conflict it has adopted a balancing position. In Belarus Moscow’s aim seems to be largely defensive, to avoid what for Putin would be a Maidan-style distater. But it has not foisted on Lukashenko a complex or expensive new integration with Russia. The Russo-Belarusian integration agreement of November 2021 is an empty letter. With Lukashenko beginning to plan his exit,

the main objective for the Kremlin is to maintain a controlled, pro-Russian transition of power. It wants to prevent Lukashenko and the Belarusian elite from casting around in search of new allies and hatching harebrained schemes. Such behavior might escalate the domestic situation and prompt the EU and the United States to look for new approaches, which might again steer Belarus toward the West.

As for Ukraine, the decisive escalation in the spring of 2021 was triggered by actions taken on the Kiev side over winter of 2020-2021.

In December Ukrainian Defense Minister Andrii Taran announced that Ukraine hopes to receive a NATO Membership Action Plan (MAP) at the upcoming NATO summit.

He stated this at a briefing entitled “Defense aspects of Ukraine’s Euro-Atlantic integration: key aspects and tasks for the future,” according to the Ukrainian Defense Ministry’s website.

“Please inform your capitals that we count on your full political and military support for such a decision [granting Ukraine the MAP] at the next NATO summit in 2021. This will be a practical step and a demonstration of commitment to the decisions of the 2008 Bucharest Summit,” Taran said, addressing the ambassadors and military attaches of NATO member states, as well as representatives of the NATO office in Ukraine.

According to him, today Ukraine’s course for full membership in NATO is enshrined in the Constitution of Ukraine, and the rapid receipt of the NATO Membership Action Plan is a goal set in the recently adopted National Security Strategy of Ukraine. Taran noted that over the past seven years, Ukraine has firmly defended not only its own independence, but also the security and stability of Europe, and acts as a powerful outpost on NATO’s eastern flank.

“We believe that Ukraine and Georgia’s joining the Alliance would be the right decision for NATO. Our countries have a lot in common. These are post-Soviet republics, the countries that have been affected by Russian aggression. From our point of view, Ukraine’s and Georgia’s potential membership in NATO will have a significant impact on Euro-Atlantic security and stability, in particular in the Black Sea region,” Taran said.

2021 February, in an unexpected move the Ukrainian authorities announced severe sanctions against pro-Russian politicians and media. On February 2, Zelensky shut down three pro-Russian TV channels, accusing their owner of financing Donbas separatists. This was followed on February 19 by sanctions against Ukrainian and Russian individuals and companies on the same charges. Most dramatically, Kiev struck against Viktor Medvedchuk, who in recent years has been Putin’s only interlocutor in Ukrainian politics and is a crucial go between. Given the strong support for his pro-Russian party Medvedchuk was also a serious challenger to Zelensky in political terms.

Clearly this merited a reaction from Moscow. In direct response, Moscow unleashed the separatist forces in Donbass resulting in a surge in ceasefire violations. But intensifying the fighting in Donbass was one thing, why the full-scale military mobilization?

Here the military logistical issues may play a role. Russia has the means. But it also had the motive not simply to intimidate Kiev but to test the relationship between Kiev and Washington. It was in early 2021 that Moscow source began to refer more often to Mikheil Saakashvili syndrome. Would Zelensky attempt something similar in Donbass in 2021, in the expectation of American support?

The Kremlin does not treat Ukrainian politics very seriously. They are strongly convinced that the real force in deciding Kiev’s actions is Washington. Russia had nothing good to expect from an in-coming Democratic administration and Biden had made clear his determination to take a firm line in the campaign. The attack on Alexei Navalny and his jailing added further tension. By raising the military pressure on Kiev, Moscow would test Biden’s mettle and make clear that if the Ukraine situation was to be resolved, then Washington could not rely on Europe to deliver a resolution by means of the Minsk process.

During the crisis, Kozak, who is also the Kremlin’s deputy chief of staff, essentially repeated President Vladimir Putin’s earlier stern warning that a Ukrainian offensive in Donbas would spell the end of Ukrainian statehood. And Washington responded.

Throughout 2021 the Biden administration has walked a line between seeking a working relationship with Russia and responding to pressure to take a strong stance on what are judged to be Russian provocations. Given that the Biden administration’s clear focus is on China it is striking how much attention has been directed towards Russia.

From this initial escalation in the spring, triggered by Zelensky’s moves against pro-Russian political forces, by way of the telephone diplomacy with Biden, which led to a deescalation in April, to the June summit in Geneva, the sparring in the summer, and the reescalation of tension since August, we can retrace the steps which by November led back to an acute war scare.

On the Russian side, one significant moment in the longer-term may turn out to be the publication on 2 July 2021 of Russia’s new National Security Strategy. Even more explicitly than its predecessor document of 2015 it sets out a new and antagonistic view of the world.

On the Ukrainian side one might point to the Crimean Platform summit that president Zelenskiy opened in Kiev on 22 August, “to build pressure on Russia over its annexation of the Crimea territory, …Officials from 46 countries and blocs are taking part in the two-day summit, including representatives from each of the 30 NATO members. The U.S. delegation is headed up by Secretary of Energy Jennifer M. Granholm.”

The structure of this conflict is clear as are the routes which generate escalation. The question is, can it be resolved? Personally I am sympathetic to Anatol Lieven’s take in the Nation. Or the proposal by Thomas Graham (NSC Russia Director for George W Bush) and my colleague Rajan Menon in Politico.

Whichever route one proposes, it will be a disaster for US grand strategy if the upshot of the current crisis is a military escalation or an increase in hostilities with Russia that drives if further towards China. The Putin-Xi summit is already scheduled for the winter Olympics in February.

Credits | Adam Tooz

Very rich articles. Many topics are relevant to my present studies. Helping me to tune into regional and international politics which are relevant to my studies. Kudos.